At Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center, the Technology and Social Change Research Project (TaSC) studies how networked social movements use social media to reframe, and often remix, the news. Memes, hashtags, and YouTube videos spring up around controversial stories during breaking news events, such as hotly contested elections and crises, manifesting in hyper-partisan talking points, and often, weaponized disinformation. Whether they are alt-right trolls trying to trick reporters into misidentifying a mass shooter or foreign interests impersonating black activists, media manipulators come together in loosely-formed coalitions to coordinate during periods where breaking news is unverified and unstable.

At TaSC, we are tracking disinformation surrounding the Canadian elections on October 21, using a digital ethnographic approach to investigate online communities and media movements amplifying and generating content that bends and distorts information for political gain. We study both successful and failed manipulation campaigns, looking at the artifacts and instructions left behind by manipulators attempting to plant false information in front of journalists, and influence perceptions of social media users. As journalists and researchers brace for this onslaught of increasingly polarized political attack ads and deceptively framed information, no amount of preparation can defend against the reckless actions by the candidates themselves.

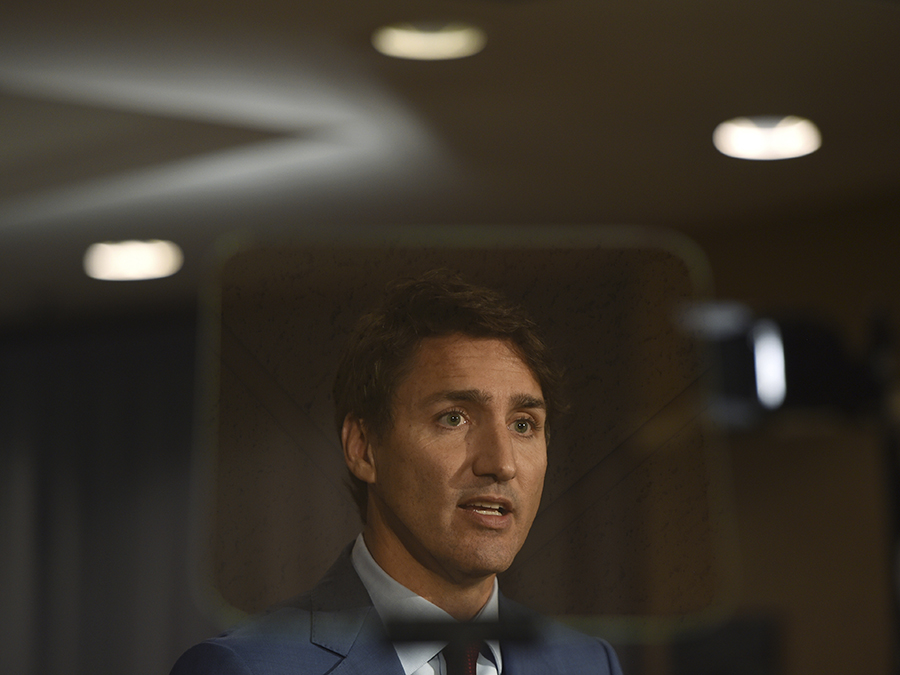

We have found that the widely reported Trudeau black and brownface story has created an information environment ripe for exploitation by partisans and other bad actors seeking to spread confusion, division, and hate. First, while the Trudeau black and brownface photos are authentic, journalists should be prepared for an onslaught of doctored pics around this news story and others like it, making it harder and harder to tell a legitimate news story from a partisan fake.

We have seen this already with the manipulated Pelosi video and the fake photo of a Parkland student ripping up the Constitution and journalists should be ready for even more sophisticated attempts to plant false narratives and to spin disinformation via legitimate news stories too.

Second, the Trudeau controversy, and emerging disinformation, trolling, and messaging around it, may already be having a chilling effect on discussion and engagement, particularly among minorities.

The Trudeau controversy, and emerging disinformation, trolling, and messaging around it, may already be having a chilling effect on discussion and engagement, particularly among minorities

To begin with, the leak has intensified polarization around issues of race, particularly systemic racism. Blackface and brownface practices have a distinctly racist history and origins, but discussion of that history, and racism in Canada more generally in the course of the election, is now complicated by crude politics, and subject to misappropriation and abuse by partisans for political gain.

On September 18, Time magazine reported that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who is running for re-election, wore brownface at a work party in 2001. That story surfaced other images of Trudeau wearing blackface and brownface, as reported in Canadian media outlets, including a brief video. During the series of revelations in the press, Trudeau addressed the reported instances of racist face painting and costuming, while acknowledging the veracity of the photos.

National and international outlets were quick to pick up the story, republishing the report with their own political framing. More left leaning outlets like the Toronto Star, for example, quoted Liberals defending Trudeau from accusations of racism by pointing to his record on promoting equality, while Jagmeet Singh, candidate for the New Democratic Party, questioned that record.

Meanwhile, conservative opinion writers and pundits decried a supposed double standard being applied to Trudeau and other Liberal politicians who have been accused of racism and other violations of politically correct norms. These pundits claim mainstream press and voters are more likely to ignore racism and gaffes by liberal or progressive candidates for actions that would be damning for their counterparts on the right, and have subsequently been urging Canada’s left to abandon the Liberal candidate during this close election season.

Other right-wing outlets like The Rebel have employed the scandal to attack other Liberal candidates. The Post Millennial, a growing conservative news site with ties to right-wing political operatives and advocacy, has been deeply critical of Trudeau since its inception in 2017. Not surprisingly, the outlet quickly reposted the story with its own conservative editorial framing. This initial repost was followed by a flurry of spin-off stories mocking Trudeau for his missteps, and promoting his Conservative opponent Andrew Scheer. The staff has an ongoing collection of the “best” memes mocking Trudeau, including his racist gaffes. Using social media analytics, we see that the photos have been widely shared among known U.S. right-wing operators who have also amplified disinformation in the past, including Andy Ngo and Jack Posobiec.

All of this polarization around race has important consequences. There is extensive literature on how such polarization has a chilling effect on political participation and discussion. People often self-censor out of fear of being ostracized from a group or broader society for expressing an unpopular opinion. Research on this “spiral of silence,” as it is called, has shown that as political climates become more polarized, people may avoid participating in political speech or engagement.

Research has shown that as political climates become more polarized, people may avoid participating in political speech or engagement

The controversy has also led to the generation and circulation of photoshopped racist blackface and brownface images and memes online, often under false pretenses. This is not unexpected. In a new report on audio-visual manipulation from Data & Society, Britt Paris and the Shorenstein Center’s Joan Donovan describe how photoshopping images to produce “cheap fakes” can be an effective tactic to trick audiences into believing a hoax. Cheap fakes use conventional techniques like speeding, slowing, cutting, re-staging, or re-contextualizing footage.

Examples of racist “cheap fakes” in relation to the Trudeau’s black and brownface controversy include racist defacement of actual political ads, generation and circulation of fake ads, and employment of images that recycle crude racial stereotypes.

Such divisive cheap fakes can also have important social and political impacts. The spread of faked blackface photos—both those intended as satire as well as those created out of racial animus—and other racist imagery and stereotypes can have corrosive silencing effects. That is, it fosters a climate of hostility that re-enforces racist stereotypes and chills the speech and engagement of visible minorities, the usual targets of such abuse.

Other aspects of the Trudeau blackface story make it uniquely vulnerable to disinformation and its chilling effects. First, though Trudeau has confirmed the authenticity of the widely reported images, there remains some uncertainty about how they were leaked or disclosed to media outlets. The surfacing of three incidents of Trudeau in brownface and blackface at the same time suggests a possible coordinated effort to upend Trudeau’s campaign for re-election. At least one independent Canadian journalist has suggested a coordinated “dirty tricks” campaign behind the scandal. And, in fact, Global News has confirmed that the Conservative Party of Canada was the source for the blackface video it reported.

Second, Trudeau has refused to rule out the possibility there may be more black and brownface images or videos that could surface. Third, Canadian and international news outlets, in declaring newsworthy and publishing old yearbook photos and a grainy, low quality video clip from the early 1990s, will likely further incentivize what one of us (Joan) has called digital dumpstering—combing through bits of digital information, records, data, and media, to shame or embarrass candidates or spread confusion for partisan gain.

These kinds of uncertainties and conspiratorial dimensions help foster a media environment easily exploited with cheap fakes and other forms of disinformation, as well as sow confusion, division, and distrust in the authenticity of information. For example: Virginia’s Democratic Governor Ralph Northam’s swift reversal of admission of a 1984 medical school yearbook page showing a person dressed as a Ku Klux Klan member and another wearing blackface.

Under growing pressure to resign from office, Northam first issued an apology for past wrongdoings. The following day, however, Northam unequivocally reversed his statement and denied all claims that he was in the photograph. The Northam incident raises serious concerns about the role of plausible deniability in the age of digital dumpstering and routine media manipulation. While Trudeau has acknowledged the authenticity of his black and brownface photos and Northam has not, uncertainty surrounds both cases. Northam, through denial, has created uncertainty about whether he was indeed in KKK garb or blackface. And Trudeau, by failing to rule out other blackface instances, has created uncertainty about whether new photos will emerge.

The Northam incident raises serious concerns about the role of plausible deniability in the age of digital dumpstering and routine media manipulation

For motivated political opponents, these moments of uncertainty provide great opportunity for the creation of hoaxes. This will include cheap fake images originating in places we associate with disinformation like 4chan and Reddit, but also those exploiting the fine line between joke, satire, and disinformation noted earlier.

At TaSC, we expect more disinformation, manipulated/fake Trudeau images, and digital dumpster-diving will come out closer to the election on October 21. In fact, we are already seeing this. An example is an image of a former Canadian prime minister from an indigenous ceremony being circulated and falsely claimed by partisans as comparable to Trudeau’s blackface.

Such disinformation and manipulation also has chilling effects. As misinformation floods political discourse in the heat of an election, it can create what Zeynep Tufekci calls “censorship by disinformation,” where members of the public, unsure of what is real or fake, are chilled from political engagement or collective action. The result is far fewer voices and much less vibrant and healthy elections—and democracies.

TaSC’s study of the Canadian election is supported by The Digital Ecosystem Research Challenge, an initiative led by McGill University and the University of Ottawa that is made possible in part by the Government of Canada’s History Fund Grant.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled Jagmeet Singh’s first name.