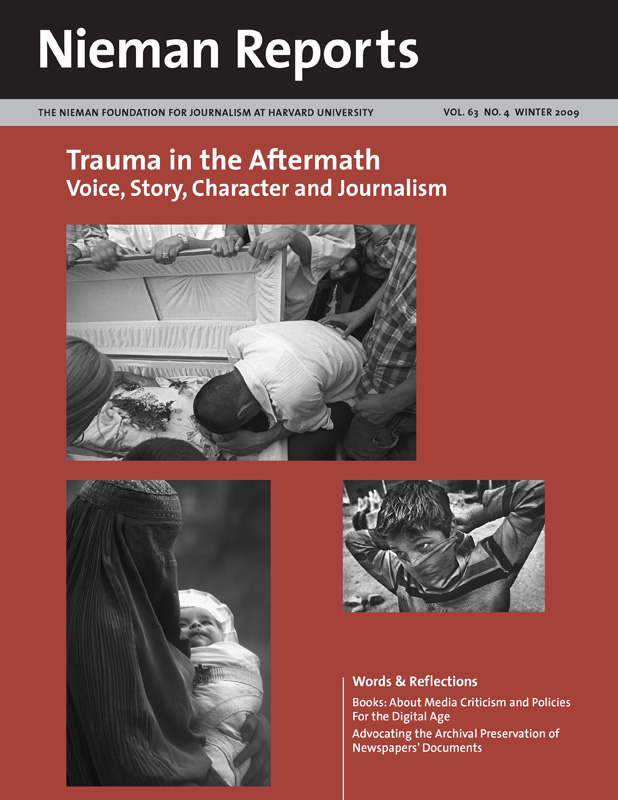

As tens of thousands of evacuees waited without food or water, the convention center in New Orleans became an epicenter of despair. Angela Perkins pleaded with the world with her cry, “Help us, please.” Photo by Ted Jackson/The Times-Picayune.

RELATED ARTICLE:

“Bypassing the Easy Stories in the Big Easy” by Jed HorneJed Horne was an editor and reporter with The Times-Picayune in New Orleans for 20 years before leaving in 2007 to write books. He is the author of “Breach of Faith: Hurricane Katrina and the Near Death of a Great American City,” published by Random House in 2006. During Hurricane Katrina, he was metro editor of The Times-Picayune. In the Fall 2007 issue of Nieman Reports, which focused on post-Katrina reporting, Horne shared ideas about how out-of-town journalists might approach coverage of the storm’s long-term aftermath. Edited excerpts from his remarks at the “Aftermath’’ conference follow:

What characterized the ordeal that we went through with Katrina was the intimacy of our experience. Intimacy in the sense of the obscenity of what had happened and also in the sense of being stripped away and laid bare in the eyes of the world and brother and sister media operatives. Among us there was the more agreeable sense of intimacy that came with being a band of journalists—given that so many others operated in the same manic way that we did for so long.

Journalism is ordinarily a very aloof practice. We’re instructed to be objective. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle is somehow suspended for journalism; we’re able to interact in environments without leaving any trace of ourselves on them. And if there is a trace or if there’s a conflict of some sort, you’re meant to recuse yourself. Acquaint your editor with the problem, and then recuse yourself.

We did not have the luxury of recusal. I remember at one point a great and belabored, rigorously ethical discussion on how we were going to deal with the fact that so many of our staff—many of them homeless, after all—now found themselves involved in a class action suit against the Army Corps of Engineers. How were we going to be able to report on this?

One of our most important reporters in the Katrina coverage was Mark Schleifstein, who had lost his home and who duly was going to sue the Army Corps. We worked out some elaborate and, I think, partly self-deluded mechanism through which we would somehow exempt certain people from covering lawsuits and require disclaimers from others. Ultimately those kinds of concerns began to seem sort of metaphysical and beside the point as we embraced this event in all of its dynamism and all of its intimacy.

Watching TV one night, the news comes on and it’s just one of these in one ear and out the other things. Some maniac has been picked up by the cops driving down Napoleon Avenue—which is one of the big thoroughfares in New Orleans—bashing his car into other cars and, when police finally stopped him, trying to run them over as well, it was a classic attempt at “suicide by cop.’’ I woke up the next morning to find that this person was a good friend, a photographer at the paper, who had simply gone bonkers for various reasons characteristic of the time. Other reporters went bonkers in print—notably Chris Rose, who wrote in a fascinating and courageous way about his breakdown. My concern as a newsroom manager is that nothing was found to be more therapeutic than work, indeed overwork. People were just truly undermining their health through the kinds of hours, days, weeks and months they were putting into their job.

The danger was, of course, that all of this was going to come to a crashing halt, and the people who had somehow sustained themselves on manic energy were going to crash a little more horribly. So it became a business of easing them away from burnout, and trying to let them down gently into a more sustainable pace and level of productivity. I think we succeeded in most cases in making that happen without folks disintegrating.

Horne describes the approach he took in writing his book, one that he decided to follow as he’d observed the coverage of extremes that dominated so much of the out-of-town and some of the local reporting about New Orleans and Katrina. Here is an excerpt from his remarks:

All of a sudden there in print were lurid stereotypes of a city described as “bestial,” as a “bunch of looters and rapists”—details later proving to be false. It occurs to me that if you are going to describe a young couple that simply walks away from a child that has expired of asthma; the sewage-stained carpeting of the convention center, and just toss it off into the 18th paragraph of a story as an example of something that was going wrong in New Orleans, that’s not an interesting detail. That’s a redefinition of human depravity and you need to, I think, frame it and herald it in that way; and maybe in the course of that time you’ll discover that it was a falsehood as well—as it was, indeed.

The goal was to find people able to tell their stories. I looked for people who told more reasonable stories, rather than the extreme stories, because I didn’t think they were that representative. By definition the extreme stories are not going to be that representative. It seemed important also to broaden the sort of dramatis personae, and include more than just the destitute.

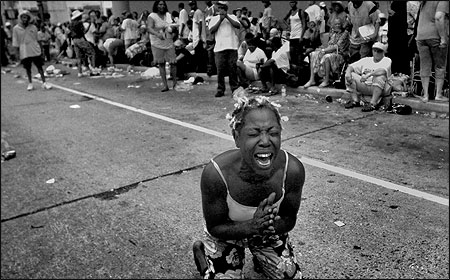

The corpse of Alcede Jackson was reverently laid out on his front porch in Uptown New Orleans, covered with a blanket and held down by slate. The body was left abandoned for 17 days with an epitaph on a poster board, “Rest in peace in the loving arms of Jesus.” Photo by Ted Jackson/The Times-Picayune.

Brett Myers is a field producer for Youth Radio, Youth Media International’s National Network, which includes Youth Radio bureaus in Atlanta, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., as well as collaborations with partners throughout the country.

Jiarra Jackson is a New Orleans native who was a reporter and host of Youth Radio’s “Generation Katrina,” an award-winning radio documentary. Edited excerpts of their presentation follow.

Brett Myers: Youth Radio began almost 20 years ago at a time of escalating violence in California, and it was a violence that was particularly known by young people. So Youth Radio was a way for young people to tell their stories in a more unfiltered way. And our model is that young people work with adult producers to learn the trade and the skills of journalism so they can tell all of the stories that are important to them—the light stories, the dark stories. From the beginning, Youth Radio was about internal narratives. To think about Youth Radio in the most practical way, we function as the youth desk for a lot of major news organizations that don’t often cover—or really know how to cover—youth news on a regular sort of daily grind.

Youth Radio’s Katrina coverage started the day the storm hit, when a young person in our newsroom in Oakland said, “This is important to me. I see relevance to my life. This is something we have to cover.” Others agreed. So without a bureau in New Orleans and without funding, our Katrina coverage started because it was our beat. In that first year, we did a documentary—all youth produced. Then we hit the one-year mark and started to encounter some Katrina fatigue: tired of hearing these stories, hard to get them on. Some of our early stories were produced for National Public Radio and various media outlets.

Listen to “Generation Katrina” at the Youth Radio Web Site.So at the one-year mark we started “Generation Katrina,” which would become our second documentary from New Orleans. If it wasn’t for Public Radio International (PRI), then a lot of our stories would not have found a home. PRI gave us a home for these stories, done by a team of youth journalists from around the country who came to New Orleans. They worked with adult producers in hitting the ground to find stories that were important to young people and young people who could tell the stories. A lot of young people we found we invited onto the team: “You’re really talented, you’ve got a story,” we’d tell them. “We’re going to train you, and you’re going to be the reporter on the story.” Jiarra Jackson, who was a student at the University of New Orleans, is one of those young people and she became a reporter on this project.

Jiarra Jackson: What I expected out of the project was that I’d be their tour guide to bring them to devastated areas such as the Lower Ninth Ward, and show them what Café Du Monde was so they could eat beignets. Instead, I was really surprised that they wanted to know what we, as the youth, were actually building with after the storm, what we’d encountered, and how we were transitioning to our newer selves.

I was kind of reluctant to share my story with them at first. I’d heard so many disturbing images and I really did not want to share my story and have it twisted into the wrong words. I was like, “Well, what do you want to know?” Once I understood that she really wanted to find out what was going on, I told her that I’d evacuated to St. Louis, Missouri without my family because I wanted to continue with my education. So I went to this city I had never been by myself just so I could continue with my education, and she was, like, “Well how did you make it through that?” And I was, like, “Through Bounce music.” And she was, like, “Really? I’ve never heard of Bounce music,” so I played a few things for her.

To hear Bounce music, listen to an excerpt from “Generation Katrina.” And then hear Jackson and Myers talk about its importance to her story and its telling. Here’s an excerpt from Myers:

If you think about the trauma that was done to that city with the hurricane, one of the main traumas was—is all of this culture going to be washed away? So doing a story about music has relevance because it’s part of the entire culture, and it’s also a way of talking about trauma, not in an I’m going to stab you in the stomach, make you cry kind of way. Those kind of traumatic stories are out there.

Brett Myers: Let me give you a broad picture of the kind of topics and stories we covered in the one-hour documentary. There’s a street corner conversation between 10- and 12-year-old boys talking about gun violence in their neighborhood. They talk about watching people die, how it makes them feel about their neighborhood, their home, and how it’s changed after the storm. There are spoken word poems and there’s a profile of the Vietnamese-American community in New Orleans East showing how the generation of young people there vaulted to become the leaders of the community because they had the English language skills to battle government bureaucracy that was trying to reopen a toxic landfill in that neighborhood. They also had the Vietnamese language skills to unite the community around the fight.

Then there’s a story about God and Katrina; we asked young people in New Orleans, “How do you feel about God and Katrina? Was there any relevance? Do you believe in God?” And most young people we spoke with said, “I think God sent the hurricane to my city to cleanse it of its evils.” A shocking number of young people said that, and so we put that story out there. But by putting a story out there does it absolve the other wrongs that were clearly a part of the storm—the slow federal response, the weak levees, all of that?

So the whole point of each of these stories was not just that listeners could learn from the documentary, which I hope they did. But it was also so the young journalists from New Orleans could own the narratives that they were putting out there. To stand behind it and feel like “that’s my story, and I told it in the way I wanted to tell it.”

Listen to a story from “Generation Katrina” in which a family in the city’s Lower Ninth Ward talked for the first time among themselves about the experience they had together during Katrina. Here is an excerpt as Myers describes how this family’s 14-year-old daughter became the reporter on this story:

It needed a different treatment, so we decided that the 14-year-old, the eldest child, Angelica Robinson, would be the reporter for the story. And 14 is really the youngest possible age you could be to tell a story of this gravity and emotional intimacy and complexity. So we went back, and I spent a week with her working on and off, choosing the best clips, producing other stories in the process, and then writing a script, and she voices the story.

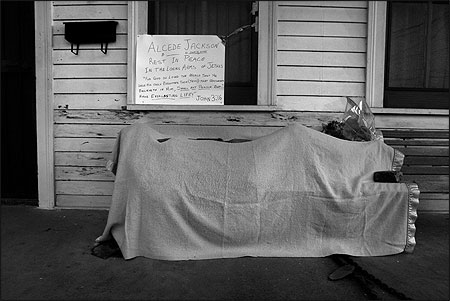

Firefighters struggled to start a small floating pump to fight a raging inferno in the wake of Katrina, in an attempt to keep it from spreading to the next house. “It’s the best we can do,’’ one fireman said. Photo by Ted Jackson/The Times-Picayune.

Larry Blumenfeld writes about culture and his stories have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Village Voice, The New York Times, and Salon, among other publications. As a Katrina Media Fellow for the Open Society Institute, he mined cultural recovery in New Orleans. Edited excerpts from his talk follow:

The B-roll of every broadcast story started with a trumpeter or with the second line or with some element of New Orleans culture that we can visually remember but know nothing about. The B-roll is where the stories that I was interested in lay. And they were important stories in a complete telling of the continuing trauma in New Orleans—and it has been a continuing trauma as last year 4,500 units of public housing were bulldozed. You cannot understand New Orleans without understanding its culture. To understand what was needed in New Orleans, what was happening in New Orleans, you need to understand what was happening to the culture and how elemental the culture would be to whatever the new New Orleans would be. I talked to people who were panicky or cynical about what that new New Orleans would be.

I want to make the case that there was also just a trauma to culture. In other countries—both developed and undeveloped—if a cultural center were under water and embattled there would be a different sort of outcry beyond the humanistic and political outcry. In New Orleans people told me what they fear and are experiencing is erasure. That they are being erased, and their history is being erased. I think that’s a really deep trauma that we need to pay attention to, and that’s been something that I was able to get across.

I agree with Jed [Horne] that in the immediate wake of Katrina the story was well told primarily. But beyond that it was poorly told or not told. And the continuing trauma was largely ignored, especially as it related to race, poverty, inequity and urban ills. And I think those things were really well addressed and differently addressed through culture.

Listen as Blumenfeld describes the ways in which he developed stories around what was happening with New Orleans’ cultural life. Here is an excerpt about one of the city’s core traditions, the jazz funeral’s second line parade:

Any Sunday through most of the year you can go to these parades; hundreds and hundreds of people for hours following brass bands. If that was shot from above on CNN it would look like, “Wow, in the wake of all this these people can have this rolling party and can dance. That’s really nice.” If they went down to the ground and spent four hours, you would see that this was the political statement at that moment. This was the assertion of their right to return.

Patricia Smith’s fifth book of poetry, “Blood Dazzler,” chronicles the human, physical and emotional toll exacted by Hurricane Katrina. Her poems have appeared in a wide variety of publications and she has read her work at venues around the world. For her presentation at the “Aftermath” conference, she recited a poem based on a news story she’d read.

ST. BERNARD PARISH, Louisiana, September 7 (UPI) – Thirty-four bodies were found drowned in a nursing home where people did not evacuate. More than half of the residents of St. Rita’s nursing home, 20 miles southeast from downtown New Orleans, died August 29 when floodwaters from Hurricane Katrina reached the home’s roof.

I do a lot of stepping into other people’s shoes. I have persona poems written in the voice of skinheads, an inner city undertaker, and what I wanted to do in terms of persona was I wanted to take those 34 people and wind the clock back for a second, and just give them a moment of their voices back. So they could say not “I was,” but “I am.”

Hear Smith read her 34-stanza poem. One stanza reads:

We are stunned on our scabbed backs.

There is the sound of whispered splashing,

and then this:

Leave them.