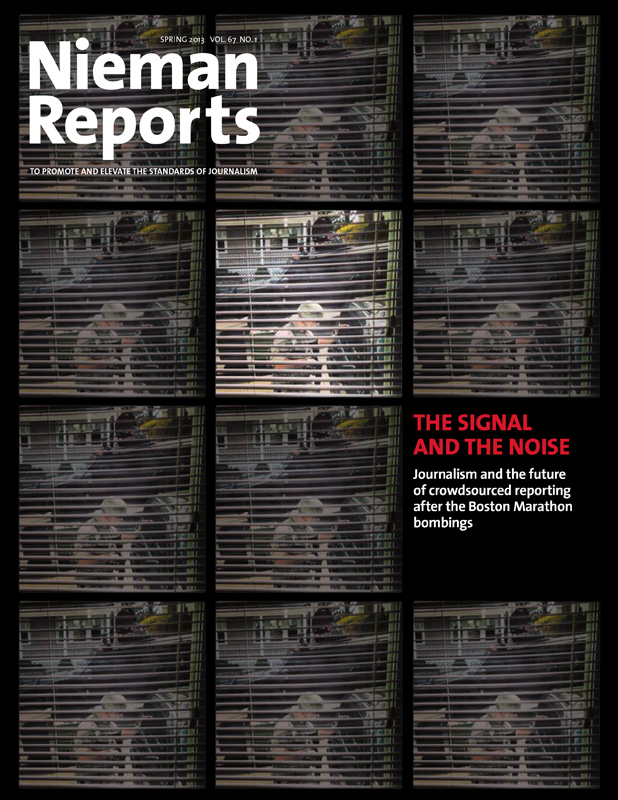

Residents recorded the manhunt in Watertown. Photo by Michael Dwyer/The Associated Press.

After the manhunt in Watertown, Hong Qu, a visiting Nieman Fellow, wrote a story for the Nieman Reports website about Twitter and credibility. I read it a few times. There was something provocative and useful about it, but also something amiss.

Hong is developing a tool called Keepr to help journalists sift through the noise on Twitter to find credible information. (For more on Keepr, see “Organize the Noise“) During the manhunt, he used Keepr to build a list of the most-cited sources of information about the search and then sift through those sources for the ones who seemed to be providing credible information from the scene. “Four factors stood out in my mind as indicators of credibility,” he wrote: “disclosure of location; multiple source verification; original raw footage; accuracy over time.” Using those criteria, he built a list of people to follow.

It’s a fair bet that there were more non-journalists than pros at the Boston Marathon bombings and close to the Watertown manhunt, and yet 18 of the 20 members of Hong’s group of highly credible, on-scene tweeters were trained journalists or journalism students. If Twitter and other social media networks are fulfilling their promise as an easy-entry platform for citizen journalism, why weren’t there more amateurs on that list?

Part of the answer may be the way the list was developed. Journalists who are “eyewitnesses” to a major news event often begin with more Twitter followers, which could push them to the top of Keepr’s lists. But I also think professional journalists dominated that list because the quality of their tweets was significantly higher than those of the average eyewitness. Most professional journalists are taught to keep ourselves out of the story, so our Twitter followers get fewer low-value tweets (“So freaked out right now! #boston #manhunt”) and more high-value—and retweetable—information (“@Amtrak says it will close train service into/out of #Boston during #manhunt”).

Journalists at the scene of a major event also might be speaking as eyewitnesses, but they are eyewitnesses with an important set of shared practices and values related to newsgathering. They have been trained in the precise skills that make them most useful and interesting during events like the manhunt: source verification; fact checking; writing, video and photography; and distilling complex events for public consumption. For many non-journalists, combining breaking news with a Twitter account is like handing a 15-year-old non-driver the keys to a Maserati. You can expect some high-speed misbehavior.

The remedy is not just rethinking how breaking news is covered, but thinking about how we can put reporting standards and skills, as well as publishing tools, into the hands of citizen journalists. For those who hope citizen journalism can fill in the gaps where traditional media organizations have withdrawn or vanished, Hong’s credibility index threw an important signal. If only 10 percent of his list of “credible” Twitter sources were amateurs, citizen journalism is struggling.

I’ve made my career working in and studying communities where professional journalists are an endangered species, communities like Forest City and Monroe in North Carolina; Pocatello, Idaho; and Blair, Nebraska. Boston, Cambridge and Watertown were, in the sense of media presence and reporting, well-equipped to cover these events. That’s not true everywhere, or even in most places. Try this little thought experiment: Imagine a fertilizer plant explosion that kills 14 people, injures 200, destroys at least 50 homes and taints the water supply. Imagine that it happens in Boston, instead of West, Texas, in the same week as the Boston Marathon bombings. How do you think the story would have played?

Wherever there are people, there is news, but it goes unreported without someone to pull the threads together, talk to people, and sift through chatter and paperwork for the facts, trends and stories. That’s why coverage of the Boston bombings makes me think of places in America that are becoming news deserts.

This is not just a question of how we cover massive tragedies. According to the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, 16 percent of Americans live in rural areas, the places least likely to be served by the kind of jostling media presence you find in Boston. Rural journalism suffers from the same problems that beset rural healthcare: a shortage of trained experts who can monitor warning signs, from cholesterol levels to the inspection status of fertilizer plants, and try to stave off a crisis. Disasters get plenty of attention, but good journalism, like good medicine, is at its best when it catches trouble in its early stages. That demands time, plenty of shoe leather and, yes, training.

I didn’t start in journalism with any special skills or powers. I had a degree in English literature. I didn’t know what a lede or a nut graf or a FOIA request was. But I was curious and skeptical, I have a powerful sense of civic responsibility, and I like knowing what’s what. There’s not some secret sauce that comes with your first journalism paycheck or a college degree. If I could become a journalist, anyone can. And I’m starting to think everyone should.

The training materials already exist, mostly for free or at minimal cost, from places like the Poynter Institute, News U, and the Knight Center for Journalism’s MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). The Society of Professional Journalist’s code of ethics comprises four simple rules that set people on the right path: Seek truth and report it; minimize harm; act independently; be accountable.

The challenge is to figure out how to promote these values to a community of people whose paychecks and professional reputations are not tied to their credibility. Useful models include Lawrence Lessig’s Creative Commons license, which brought awareness of intellectual property to the Web’s Wild West mash-up culture, and “Now You See It” author Cathy Davidson’s proposal that organizations like the SPJ could distribute badges to people in recognition of skills acquired, kind of like digital Boy Scouts. Perhaps it’s time for us to look at ways to clarify the training that all of us, pro and amateur, have received, as a statement of our standards and a starting point for credibility. I don’t know any “certified” journalists, only employed ones and, as we see in every major news event, even the standards among pros are inconsistently applied.

In thinking about Hong’s list and several others that had similar distributions of pro/amateur journalists, it seems obvious that it isn’t only the number of Twitter followers, proximity to events, or even original raw footage and quotes that matter. It’s standards and training. Those who care about journalism as a civic activity, and not just as an industry, need to work harder to distribute both.

Betsy O’Donovan is the 2013 Donald W. Reynolds Nieman Fellow in Community Journalism at Harvard University.

MORE COVERAGE OF THE BOSTON MARATHON BOMBINGS

Organize the Noise: Tweeting Live from the Boston Manhunt

By Seth Mnookin and Hong Qu

Reporting on Radicalization

By Souad Mekhennet

Curation Is the Key to Bringing Social Media and Journalism Together

By Ludovic Blecher

New Challenges, New Rewards for Journalists on Social Media

By Borja Echevarría de la Gándara