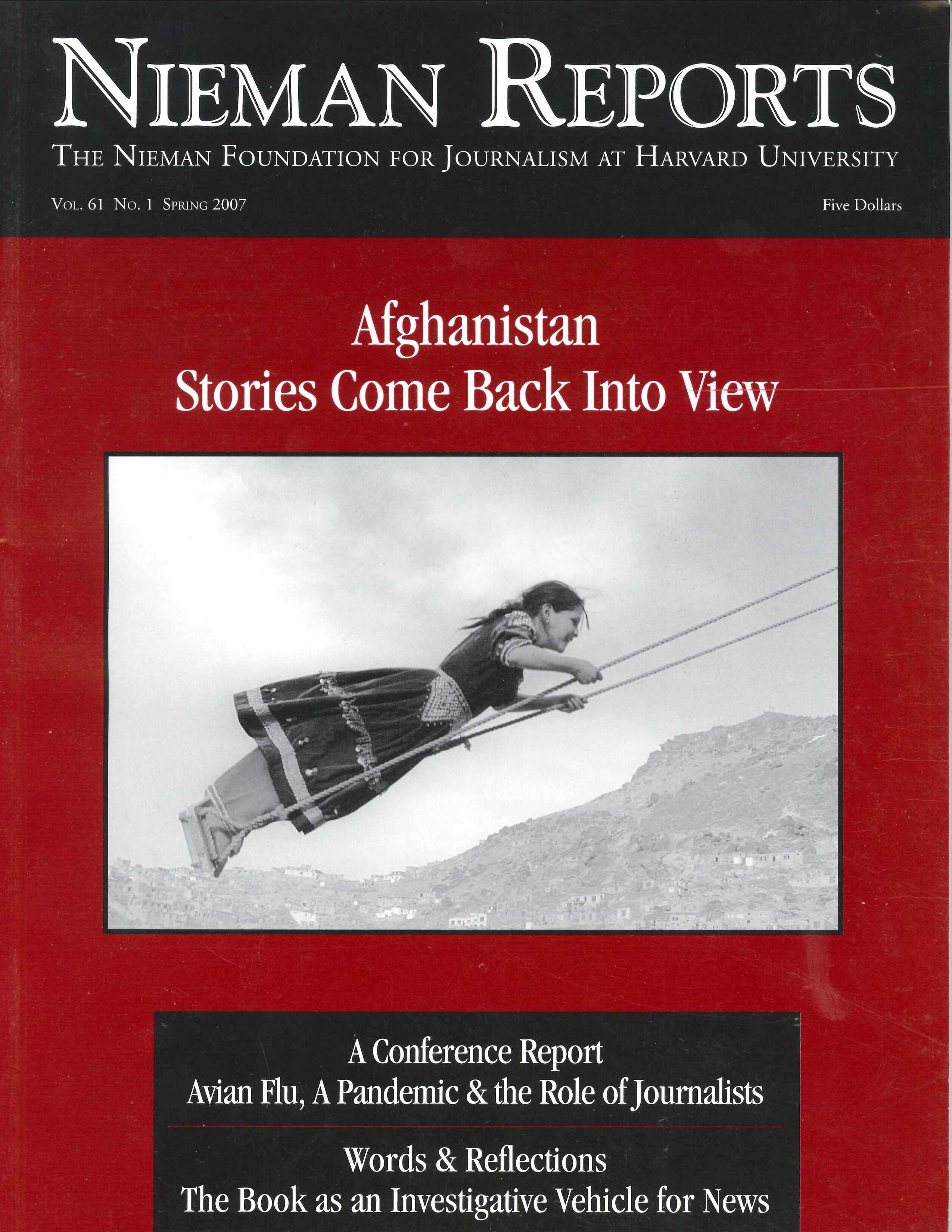

A man wears a rooster head to publicize bird flu prevention on the streets of Xi’an in China’s Shaanxi Province. March 2006. Photo courtesy of The Associated Press/EyePress.

Stephen Prior, Executive Director, National Center for Critical Incident Analysis

We’re dealing with an extremely complex environment — it’s a complex geopolitical environment and a complex environment from the scientific standpoint. And it is also very complex in terms of communication. So we have uncertainty and complexity. And when we have uncertainty and complexity in dealing with a crisis, the last component that comes into play is trust — trust with the public, trust with our colleagues, and trust with our families. Trust will be the paramount currency on which we decide what happens. If we’re trusted — and if the information is trusted — then we run the risk of getting it right. And that will be wonderful.

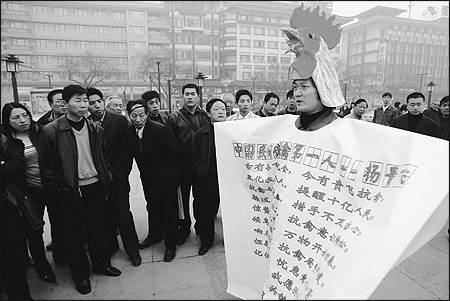

Dustin Duvall, is hugged by his mother, Elizabeth Duvall, after they were reunited outside the remains of their neighborhood in East Biloxi, Mississippi. August 29, 2005. Photo by Patrick Schneider/Courtesy of The Sun Herald.

Michael Osterholm, Director, Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy and Member of the National Science Advisory Board on Biosecurity

Wake up: It’s already tomorrow.

Pandemic influenza is not a matter of if it is going to happen. It’s not a question. There have been 10 pandemics in the past 300 years; pandemics date back to Hippocrates, and there will be pandemics in the future. The question is when, where and what will cause it. A pandemic is very different than an earthquake, hurricane or tsunami in that it will be worldwide. There won’t be 47 states coming to the aide of three Gulf states, as happened in Hurricane Katrina, or one country coming to the aide of another country in the sense that we typically think of pandemics. And that’s okay. We just have to begin to think about how we are going to prepare for it and what does that mean.

The other piece we’ve focused on so much is the 258 World Health Organization (WHO) reported cases with 154 deaths, 54 countries having avian cases, and 10 countries with both human and avian cases. Without sounding crass, that’s not the problem. In a public health world, 258 cases of anything occurring over a few years is not a big issue. It’s what it represents and the future potential that we have to look at. This is not about distinct events that so often the news media are able to cover with comfort. This is about a movement, a long-term issue. If I had a nickel for every time reporters tell me that their editors asked today why should I be covering this, I could probably retire. One thing we have to address is pandemic fatigue that reflects where we’re at today with this story.

I have yet to see a single media organization in the world that has anything beyond what I’d call a very cursory plan for how to respond; the vast majority hasn’t thought about it at all. I haven’t found one company that has bought a sufficient number of respirators that could be used every day by another person throughout the entire duration. Not having that is like buying a 40-foot rope for somebody drowning 60 feet out. This is very critical given that the news media will play a very important role during this time.

Given our just-in-time economy, the overlay with pandemic influenza is going to be huge, and yet there has been virtually no coverage of this circumstance. Today, for example, 80 percent of all the pharmaceutical products used in the United States originate in other countries. In a pandemic situation, overnight we’ll lose not just flu drugs but also most of the drugs we count on every day. We’ve looked at these supply chains and the ability to maintain them. It’s going to collapse, and there are many other supply chain issues. This is not scare tactics. I worry desperately that one day we’re going to wake up to the next pandemic, and the world is going to be surprised, and I wonder what the journalistic world is going to think they missed. Imagine if we’d had three years notice that Hurricane Katrina would happen on the day it did. What would have been done in that three-year period from the time they were notified to the day it happened? We’re notifying you now: It is going to happen.

Brian Toolan, National Editor, The Associated Press

The Associated Press’s [AP] experience rivals any other news organization in covering widespread health crises. And we’ve taken preparations to keep our journalists safe as they cover these events. So we ask ourselves now whether we are poised to provide essential coverage — to make our coverage as deep and specific as it can be — and keep our journalists safe and healthy during a pandemic. And my answer is maybe.

When the avian flu broke out in Vietnam, we did not rush immediately to the farms where hundreds of thousands of chickens were dying, but we covered the story more than adequately. When we had the right kind of equipment and supplies to provide some safeguard for our reporters, we did cover that part of the story. Our experience on that story resulted in some guidelines: Caution is our first option; reporting by phone, when possible, is an option. We’re prepared for large numbers of our staff to be telecommuting. And we’ve stockpiled protective gear that many of you would recognize — N95 masks, boots, gloves, sanitary wipes, smocks and disposable boots, and placed this equipment in a dozen domestic bureaus in large cities, with a geographical spread that was intentional. The same equipment exists in almost all of our foreign bureaus — certainly in Asia, but also in Europe and the Middle East, and AP’s bureaus, especially foreign ones, have large supplies of Tamiflu. We have 10 medical and science reporters, domestically and around the world on which we depend heavily. In the case of a huge outbreak, we’ll establish a universal flu coverage desk in New York that will coordinate all of the coverage.

What we don’t know about pandemic flu is what concerns us all. One of our Asian editors called SARS and the avian influenza "warm-ups" for what a pandemic would require. He said we’ve gotten a pale sense of the pressures and the performance expectations, but we really haven’t been truly tested. We would have to recalculate the risk of coverage in the case of a pandemic. Can the AP, or any organization, afford to have 40 percent of its staff out sick or home tending with illnesses of their family members? Would the loss of such manpower and our dependency on technology stretch technology to its limits? Where will the next pandemic arrive? We know globalization is going to be a conveyance for it, the wings of the disease. Will governments be open about what they are confronting and their capabilities of meeting the challenges of a pandemic? China’s obfuscation at the beginning of SARS was about its only dependable trait. If we don’t get honest feedback from companies, from organizations, from nations, from agencies like WHO, then journalism’s efforts are going to be compromised and populations are going to be dangerously ill-informed.

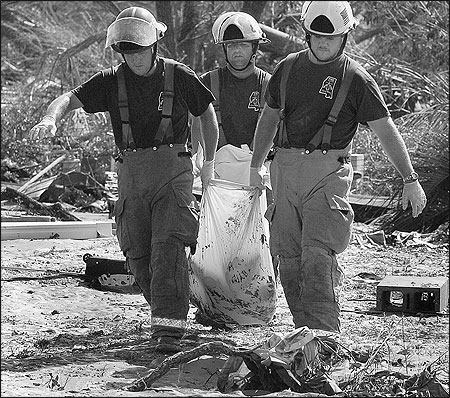

Biloxi firefighters remove a body from the Point Cadet area of East Biloxi on August 30, 2005, the morning after Hurricane Katrina demolished the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Photo by Patrick Schneider/Courtesy of The Sun Herald.

Stan Tiner, Executive Editor, The Sun Herald, Biloxi, Mississippi

Learning from Hurricane Katrina: Plan, plan, plan.

Our little eight-page newspaper we published on the day of Katrina was tangible proof that a community institution was actually working. It was evidence to the community that the center was holding, while in those early days other institutions they depended on were not delivering on expectations; some were not delivering at all. When a disaster such as Katrina or a massive health threat is upon us, we are likely to be overwhelmed. Opportunities for success and survival are connected to a good plan thought out well in advance, one that is strategic and involves communication and engagement with every person in your organization. The Sun Herald’s emergency action is updated from time to time, and it’s the working document from which we were able to publish a newspaper on the day after Katrina. Its elements cover everything from a possible bomb threat to anthrax, and on our radar screen is pandemic flu. The Sun Herald already sponsored a forum with the University of Southern Mississippi at which our state epidemiologist spoke to members of the community. We found an extraordinary level of engagement with leaders from a number of industries, such as banking and the medical field, who were extremely well informed and developing pretty comprehensive plans.

During Katrina our building sprang many leaks, but our best journalism was produced in that soggy newsroom. No employee of The Sun Herald died that day, but 60 of them lost their homes. Reporters and editors discovered slabs where their homes once stood; they came back into the newsroom where we hugged and cried together and went about our important job of bearing witness to the biggest story of our lives. The scale and scope of Katrina was greater than any plan could have anticipated, but for the most part the plan, like the building, held together. We also were nimble and adaptable to the conditions. Newspaper people are clever, and they responded to the enormous challenge with heroic efforts. And the empathy created by shared pain and circumstance gave our journalism unusual insight into the story as it unfolded day by day.

Because there were literally thousands of big stories all around us, we learned to practice journalistic triage, investigating the massive information field, producing and publishing those stories that we deemed most necessary to serve the people of South Mississippi with the news that would help them survive the initial shock of the storm. Because of the horrible and complete nature of the losses suffered, we could have gone on for months reporting nothing but stories about the loss of life and architectural and cultural and personal treasures. We were mindful, though, of the emotional trauma that was evident in almost all Katrina survivors. So we deliberately sought out stories of the many acts of heroism and selflessness shown across South Mississippi.

Early on we had a choice of two incredible stories and wonderful images that would have made our front page any day. One was about the recovery of bodies in Biloxi, where a photographer had captured a stunning image of firefighters tenderly carrying out the bodies of victims in clear plastic across a mountain of debris. The photo was backlit, creating a gossamer glow over the entire scene. It was a photo that all of us would love to have on the front page, but instead we ran a lead photo of a mother and son, uniting after a couple of days of separation and worry. [See photos at right.] The picture captured the moment of that first hug against a backdrop of utter and complete destruction. The headline proclaimed hope amid ruin. It was part of a plan to help our people recover in body and spirit on the road back from Katrina.

In these matters, constant planning and constant communication are essential. And the power of a news organization to tell its unique story would be important when faced with pandemic flu. The credibility and moral authority of a local newspaper or television station should not be overlooked as we try to create a plan to prepare for this awful threat.

Questions and Answers

John Pope, Medical/Health Reporter, The Times- Picayune, New Orleans: One thing I’ve been grappling with is preparing our readers. I’m having trouble establishing where to draw the line between preparing people for something that could be really horrible and yet not scaring them to pieces. Two years ago, when there was a flu shot shortage, people were going nuts; they were afraid that their aging mothers were going to die if they couldn’t get a flu vaccine. So I’m having a problem with this.

Osterholm: It’s going to be tough. But that is not a reason not to basically lay the truth out there and begin to think about what we will do. There’s enough data to say there’ll be more pandemics. What we don’t know is how bad they will be. If you look at SARS, it was really a minor event in the global picture. But if you were in Toronto and saw what SARS did or in Singapore or in Hong Kong, it was dramatic. To the rest of the world, it almost didn’t exist, but how many people worldwide realized that the three largest manufacturers of respiratory protection devices literally ran out of respirators in the week when SARS was winding down? They had nothing more to ship, because there’s no reserve capacity. Had SARS spread to five or 10 more countries and lasted another six months, and nobody had respirators at all, do you think health care workers would have come to work? That’s what’s going to happen in a pandemic. So that’s what we need you to be asking. Talk with your mortuary science people; ask them what they are going to do for caskets, for funerals, things like that. How are stores going to get food? Those are stories you can do now; you can reasonably ask such questions.

I don’t believe every time there’s another case of H5N1 infection in Asia that it’s a news story. What I find troubling is that most of the media is covering the science of H5N1 right now by press release. So many drug companies are releasing their new latest finding on a vaccine, which is really a nonstory to many of us, but it makes front-page news like we’ve found the magic bullet. That’s the kind of coverage reporters don’t need to be doing; they need to be doing the kind of coverage that examines local preparedness and the big picture issues. With the vaccine, I’ve never seen one journalist raise the question of who out of the 300 million people in this country would get those three million doses of vaccine that might be available. To me, this is a fundamental question, and the kind of topic about which we could find the news media doing much more coverage.

Prior: Those who receive news are incredibly unforgiving, and I think this drives a lot of news decisions. When a well-intentioned preparatory plan for something that is very possible to occur doesn’t happen, does the news audience react with relief and glee and celebration and say, "Yes, we took the protective measures and never had to use them"? No. The public reacts with anger and asks, "Why did you scare me?" News organizations are put in an incredible bind by their audience on whom they depend for revenue and who are not dying to hear about this stuff. And when journalists do tell them about it, it’s not like they want the whole story. They want pieces of it. They don’t want to be scared too much.

Harro Albrecht, Medical Writer/Reporter, Die Zeit, Germany: The United States and probably most of the world is not well enough prepared because there are not enough ventilators and, with just-in-time delivery, everything will go down. How do we cover this message? As journalists, we demand to know about solutions, but this seems an impossible job to do. So it’s hard to cover a situation in which there seems to be absolutely no solution.

Osterholm: That is a very important point, but if we had answers and solutions we wouldn’t need to do preparedness planning. It’s like the Kubler-Ross stages of death and dying. Denial is the first stage, and part of the problem is we are in a major state of denial. What we need to do is break through that, but you can’t break through so much that you leave everybody with despair. But right now the vast majority of the world does not have a clue what very well could be on its doorstep tomorrow. So part of it is you’re trying to move that. Going to local officials is critical. Not that there aren’t national or international issues, but how is your local community going to take care of thousands of extra people over eight to 10 weeks? Begin to ask leaders who will do it when it happens, because they will do it. So that’s where you have to start asking the questions. And when you stimulate discussion is when somebody comes up with creative ideas. But you have got to first challenge the system to even begin to think that people exist in these roles. That’s a critical piece.