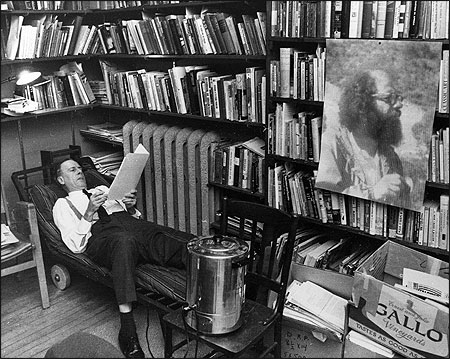

Media commentator Marshall McLuhan reads as he reclines in his study, 1968. Photo by The Associated Press.

Marshall McLuhan: You Know Nothing of My Work!

Douglas Coupland

Atlas & Co. 216 Pages.The great risk in reading Marshall McLuhan literally is that you don’t know how seriously even he took his ideas. “I don’t pretend to understand it,” he once said of his work. “After all, my stuff is very difficult.”

Yet if there was an overriding theme to which he returned again and again, it was that television—low-resolution moving pictures in a tiny box—was the ultimate “cool” medium, more tactile than visual, demanding that the audience participate because so much information was left out. Unlike “hot,” one-way media such as newspapers, radio and movies, McLuhan argued, the interactive nature of television could not accommodate controversy and overbearing personalities. Hitler, boffo on radio, never would have made it on TV.

So here’s what I would have liked the novelist Douglas Coupland to tell us in his slim, quirky, highly entertaining biography of McLuhan: Did advances in technology change television from a cool medium to a hot one? McLuhan himself, in his best-known book, “Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man” (1964), wrote that “‘improved’ TV” would no more be television than cartoons would still be cartoons if they were transformed into fine art. Could Bill O’Reilly, Glenn Beck, and Keith Olbermann have succeeded back when viewers had to infer what people looked like from fuzzy, black and white horizontal lines? Do cable pundits thrive today because we live in a politically divisive age? Or are they merely the inevitable consequence of HDTV?

Alas, Coupland’s mission in “Marshall McLuhan: You Know Nothing of My Work!“—his title is a play on McLuhan’s memorable cameo in Woody Allen’s 1977 film “Annie Hall”—is not so much to explain McLuhan’s ideas as it is to introduce us to the man himself. We learn that McLuhan may have been mildly autistic; that he had two arteries at the base of his skull, like a cat, which may have nourished his insights by providing his brain with more blood than is normal, but which contributed to the strokes that debilitated and eventually killed him; and that he had an overbearing mother and a wimp of a father. (Coupland believes the cartoon characters Dagwood and Blondie, who pop up repeatedly in McLuhan’s writings, are stand-ins for Herbert and Elsie McLuhan.) The genius of McLuhan’s ideas Coupland takes for granted, even as he chuckles at “Marshall’s tendency in later life to speak first and find the footnotes later.” Indeed, “Understanding Media” rambles on for 359 pages with scarcely any footnotes at all.

Yet Coupland offers sympathetic insight into McLuhan and his influences—no small thing, given McLuhan’s status today as a cultural icon, well known for little more than being well known and for writing “The medium is the message.” And possibly for popularizing the phrase “the global village.”

McLuhan, we learn, preferred talking in front of an audience to writing alone in a room. So it’s not surprising that McLuhan expressed his ideas more coherently in a 1969 interview with Playboy (back when some folks actually did get the magazine for its articles) than in his own turgid, convoluted prose.

A bit more than midway through the book, Coupland takes McLuhan’s grand idea and boils it down to five short, lucid paragraphs. Let me go one better and see what I can do in five sentences.

- Preliterate, tribal societies lived in an environment in which sound was the dominant sense, which in turn helped foster a communal, emotionally driven form of living.

- The rise of the phonetic alphabet shifted that dominance to the visual, which gave rise to individualism and a linear, rational mode of thinking.

- The printing press accelerated and amplified that process, leading to nationalism, industrialization and Western cultural hegemony.

- The electronic media, and especially television, de-emphasize the visual—remember he believed TV was primarily a tactile experience—and hark back to earlier modes of interpreting our surroundings.

- The consequence will be the retribalization of humanity, only this time on a global scale—hence “the global village.”

Often McLuhan was accused of being an enthusiast for these changes. Coupland refutes this charge by explaining that McLuhan hated the modern world but was compelled to describe it for our betterment. Yet in his conversation with Playboy, McLuhan sounds like he’d spent the previous week rolling in the mud at Woodstock, saying, “Literate man is alienated, impoverished man; retribalized man can lead a far richer and more fulfilling life—not the life of a mindless drone but of the participant in a seamless web of interdependence and harmony.”

From what he regards as McLuhan’s best book, 1962’s “The Gutenberg Galaxy,” Coupland also cites a passage to make the case that McLuhan anticipated the Internet “four decades in advance.” Indeed, there is something prescient in McLuhan’s words as quoted by Coupland:

Instead of tending towards a vast Alexandrian library the world has become a computer, an electronic brain, exactly as an infantile piece of science fiction. And as our senses have gone outside us, Big Brother goes inside. So, unless aware of this dynamic, we shall at once move into a phase of panic terrors, exactly befitting a small world of tribal drums, total interdependence, and superimposed co-existence.

To underscore the theme of McLuhan as Internet seer, Coupland adds some touches to make readers feel as though they are randomly surfing the Web: MapQuest directions to various McLuhan landmarks, catalog entries for McLuhan’s books, lists of various kinds, even a test to measure the extent of traits associated with autism. McLuhan may be ultimately unknowable, but such ephemera bring us closer to him.

In a 1965 profile of McLuhan, Tom Wolfe described McLuhan as a geeky professor with a clip-on tie, otherworldly and clueless about the fame-and-celebrity-driven world into which he had suddenly been thrust. His story ends with McLuhan in a topless restaurant in San Francisco, lecturing the legendary columnist Herb Caen on the deeper meaning of the breasts that were swaying around them. Caen had referred to a woman as “good-looking”—both an error and a teachable moment, in McLuhan’s view.

“Do you know what you said? Good-looking. That’s a visual orientation. You’re separating yourself from the girls,” McLuhan advised Caen. “You are sitting back and looking. Actually, the light is dim in here. This is meant as a tactile experience, but visual man doesn’t react that way.”

Such a person may seem an unlikely subject for an extended love letter, but that is precisely what this book is. Coupland is an engaging guide to McLuhan’s life and family, his academic influences and his religious sensibilities. By placing McLuhan’s maddeningly difficult ideas in a recognizably human context, Coupland helps us understand how they arose and why we’re still talking about them a half-century later.

If only he could have explained Glenn Beck.

Dan Kennedy is an assistant professor of journalism at Northeastern University. He is a panelist on “Beat the Press” on WGBH-TV in Boston and a contributing writer for The Guardian. His blog Media Nation is at www.dankennedy.net.