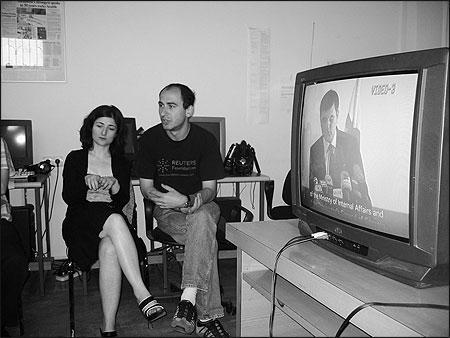

Georgian journalist Nino Zuriashvili, left, and editor and videographer Alex Kvatashidze.

Put yourself in this situation. You are working as a TV news director in a competitive market with an audience hungry for news. Like all news departments, there is a limited budget. A freelance production company offers a fully produced investigative report that documents unethical, illegal activity by a high government official. The production was done by two journalists with an established, well-respected track record, and their report includes on-camera interviews with multiple witnesses who confirm key facts, facts that are truly disturbing.

This investigative report tells the story of how a high government official ordered state police to arrest two innocent citizens who were jailed, tortured and convicted. It took several months for the production company to put this report together and, during that time, they worked on nothing else.

Technically, the production is beautifully shot, wonderfully edited. In a country with a history of often broadcasting rumor and innuendo, here is an example of meticulously fact-based, fact-checked journalism.

The production company’s asking price to broadcast this story? Free. The takers? None.

This is what is happening in the republic of Georgia. The production company is Monitor Studio, started by journalist Nino Zuriashvili and editor/videographer Alex Kvatashidze. They had worked for years on the first investigative TV news program at Rustavi 2, the television station that put free speech on the air following the collapse of the Soviet Union. But since the “Rose Revolution,” when in November 2003 the corrupt government of Eduard Shevardnadze was overthrown in a bloodless change of power, the press has taken a giant step backwards in Georgia. Rustavi 2, a station that once prided itself on hard-hitting reports about government corruption during the era of President Shevardnadze, has become a voice of the government.

Frustrated by the lack of serious reporting, Zuriashvili and Kvatashidze sought independent funding and started their own investigative production company. Finding stories was not a problem; finding a place to broadcast them was. When they offered Tbilisi TV stations this report free of charge, news managers didn’t have any editorial questions; they didn’t ask for a shorter version (the report runs 23 minutes); they didn’t ask for exclusivity. All they said was “no.”

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Sozar Subari was elected in 2004 by the Parliament of Georgia to serve a five-year term as Public Defender (Ombudsman) of Georgia. Prior to doing this, Subari was a member of the Liberty Institute, a journalist for Radio Liberty, and an editor of Kavkasioni, a newspaper in Georgia.The news contained in the investigative report came as no surprise to the Georgian news managers. They knew the story, and their reporters were already aware of it. Georgia’s Public Defender, Sozar Subari [see author’s note], had called a press conference in which he enumerated the same serious charges against government officials and departments. It was a typical press conference, with all the stations there with cameras and microphones taking in the words he said. Key points from Subari’s press conference were put into in the report Zuriashvili and Kvatashidze produced. That night on the news, however, Georgian citizens never saw a frame of video or heard his words. News managers in the post-Rose Revolution Georgia weren’t about to touch this report, which posed such direct criticism of President Mikheil Saakashvili’s government. For them, it was a nonstory. This was true even for Imedi Television, majority owned by News Corporation, where reporters have done stories critical of Saakashvili’s government when the other Georgian TV stations have not.

Once it became clear the stations would not touch this story—either as a report from the press conference or as the longer contextual piece by Zuriashvili and Kvatashidze—the decision was made to use technology to circumvent censorship and cowardice.

Using the Internet

The story of how this news report found its way to the Internet begins in a classroom at the Caucasus School of Journalism, when Zuriashvili and Kvatashidze came to show their report to the journalism school students I was teaching. Since 2001, I had trained professional and student journalists in the Republic of Georgia. During my first year there, I had worked with these two investigative journalists. Now, after seeing their report, we talked about how it might be possible to tell this story when the Georgian stations wouldn’t broadcast it. My students—from Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia—responded with a single voice: the Internet.

RELATED WEB LINK

Read Zuriashvili and Kvarashidze’s story »When I returned to Kent State University, where I teach journalism, I brought with me a mini-DV copy of the investigative report. Immediately, I brought it to my colleague, Joe Murray, who was the former director of the New Media Center at Kent State who joined the faculty at the journalism school in 2007. When reporting goes online, Murray is the one who teaches students how to get it there as cost efficiently as possible. In this case, despite several challenges we faced in making this video work for a potential audience in Georgia, the investigative report that no station in Georgia would broadcast was soon able to be seen everywhere.

Having a chance to work on this project with these Georgian journalists reminded us of what we train our students to do—use the most appropriate communication tools that are readily available to design a multimedia site so stories can be told to anyone who has a computer and Internet connection. Censorship and fear of repercussions from powerful officials will never go away. But thanks to the Internet, it is now nearly impossible to kill a story that needs to be told.

Karl Idsvoog, a 1983 Nieman Fellow, is an assistant professor at Kent State University.