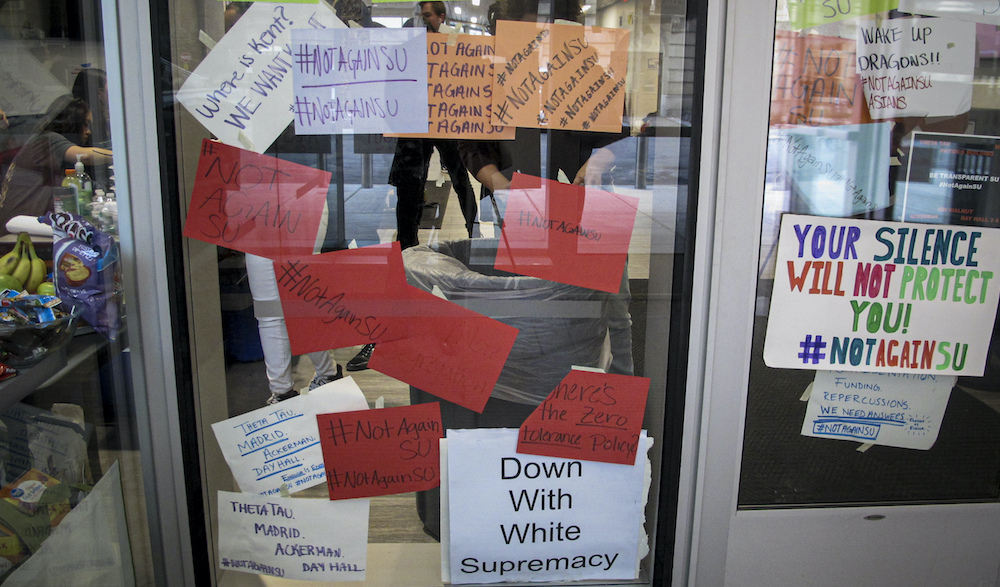

Signs posted on windows and doors at Syracuse University in the fall of 2019 display anti-racism expressions following reports of racist graffiti and other incidents at the school

The reporters were used to getting stonewalled by the administration, but now the protesters demanding change were also shutting them out.

One news organization, determined to tell the protesters’ stories, struck a deal: reporters would not identify the protesters or show their faces in photos — in exchange for access. It worked, at least until other journalists turned on them for abandoning their First Amendment right to cover the protests unfettered.

We’re sure this sounds familiar. But this wasn’t 2020, and these weren’t professional journalists covering #BlackLivesMatter protests. These were student journalists at Syracuse University, covering protests sparked by anti-Black, anti-Asian, and anti-Semitic graffiti found on campus in what now seems like the distant past of November 2019.

Student journalists at Northwestern, Harvard, and other schools faced similar pressures last fall. The Daily Northwestern started to cover protests related to a scheduled campus visit by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions as it might cover any other newsworthy event. The backlash came quickly from protesters, who felt the paper’s student reporters used intrusive tactics to track them down for comment. The paper apologized. Then came the condemnation from the supporters of a more aggressive, traditional journalism. The apology, wrote the students’ dean, “sends a chilling message about journalism and its role in society.”

As professors of journalism at Syracuse University, we saw young journalists wrestle with these issues up close. When racist graffiti appeared on campus a year after similar slurs were found, a group of students organized the #NotAgainSU protests, occupied university buildings, shined a spotlight on other racist incidents on campus, and dominated news coverage at the private university from November until Covid-19 shut down the campus of about 22,000 students in mid-March. During these protests, we saw some of our students reject journalism altogether and join the protests wholesale. Others tacked in the opposite direction and saw the benefits of remaining neutral and dispassionate in the face of a rapidly changing dynamic in which neither side wanted to engage the press.

There also seemed to be a third group, most likely always present in newsrooms but that is just now coming into focus for us: reporters who were determined to do journalism while also situating themselves as allies of protesters. Some of these reporters were members of the groups targeted by the graffiti; others saw the protesters not only as right on the issues, but also as being in a vulnerable position that required a nuanced approach.

Now, we’re seeing professional journalists face some of these same challenges in covering protests, and we’re witnessing some of the same tensions in the nation’s newsrooms. This overlap gives us hope that the results of a study we conducted at the Newhouse School can offer some insight into these newsroom conflicts, including finding common ground from which to build a constructive conversation.

After witnessing our students struggle with these issues in the fall semester, we devised a study in the spring that asked 52 students to rank 28 statements about journalism from most to least like their journalistic mindsets. The statements included items such as “journalists must maintain their independence and let the facts guide them” and “involvement by journalists in the issues they cover is a strength that gives them unique insights.”

We then employed factor analysis to identify clusters of students who had similar statement rankings. The results showed that most students factored, or clustered, around one of two distinct viewpoints that can roughly be classified as either an impartial, traditional mindset or as a more involved, empathetic mindset that we call the emerging ethos.

The traditionalist group ranked “journalists must pursue the truth, regardless of the outcome” highly, while the other group elevated statements like “journalists should take extra care when reporting on marginalized groups.” The traditionalists rejected statements such as “journalists should select stories that validate perspectives they consider just and correct,” while the other group gave low scores to statements such as “journalists should identify protesters who seek to influence public debate, even if the protesters object.”

Despite these differences, what is most surprising and encouraging to us in our research so far is how often the two divergent mindsets converge in agreement on journalism’s most sacred principles. Both groups, for instance, gave the same two statements the highest and lowest scores. The traditionalists and those who embraced the emerging ethos ranked “journalism’s first obligation is to the truth” as the statement they supported the most, and both ranked “objective journalism fails to elevate truth over trash” as the statement they supported least.

In other words, it appears from the results that the group of students with less-traditional views of journalism still value a straightforward, neutral approach — even if it is not what they themselves want to practice. One of the students who, overall, expressed the more involved mindset nonetheless wrote this in response to an open-ended question:

Even though being 100% objective … is impossible, trying to be as objective as possible ensures that readers can come to their own conclusions and make up their own minds about a certain piece of news or an event.

We plan to extend this research by having professional journalists rank these statements, and we expect additional mindsets to emerge as we gather data from a diverse group of journalists whose experience cuts across different mediums, organizations, beats, and nations. Yet we anticipate that many professional journalists will also cluster around the two mindsets that have already emerged.

Journalists of differing mindsets will inevitably work together, especially as newsrooms push for diversity and welcome an emerging generation of journalists, many of whom are wary of a tradition that might seek to limit their personal speech or remain neutral in the face of hate. But that doesn’t mean widespread disagreements are inevitable if, as we saw in our study, the underlying core values of the journalists still align.

In addition to recognizing shared core values and acknowledging the potential for journalists of both mindsets to co-exist and to complement each other’s work, a third finding from our study may also be a useful bridge between the two mindsets: a desire to refocus journalism on citizens. Student journalists of both mindsets used opened-ended questions on our survey to champion a journalism that looks out for people at the whim of the powerful.

“I believe good journalism is the bridge between those in power and those that … put them there,” wrote one of our students. Another proclaimed: “I’m becoming a journalist because I want to share the stories of people. I believe journalism is a platform to tell the public’s stories, and in many cases, spark social or societal change from it.”

One of these students grouped with other journalists who expressed the traditional mindset, the other clustered with journalists of the emerging ethos. It is hard to guess which is which. And that’s the point.

Greg Munno is an assistant professor at the Newhouse School of Syracuse University, where Megan Craig, a freelance journalist and former Chicago Tribune staff writer and editor, also teaches journalism. Their colleagues, assistant professor Alex Richards and doctoral student Mohammad Ali, contributed to the research project.