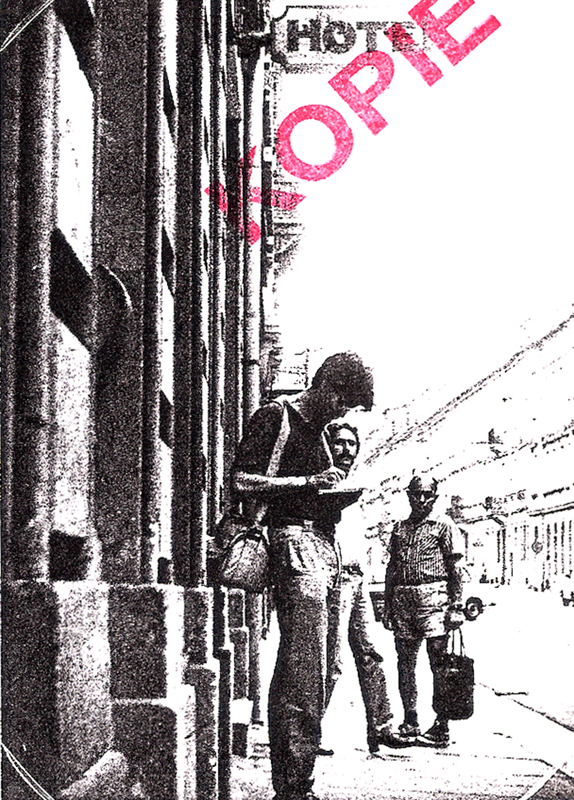

Tanner taking notes in front of a hotel. Stasi agents recorded his activities

In my first reporting job out of college, I traveled across Communist Eastern Europe and wrote travel guidebooks. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, I obtained my secret police file, which showed that Stasi agents had trailed me as I inspected hotels, restaurants, and sights.

Even with 10 men on the job one day in Dresden, they learned little about me. They noted that I had asked a guard whether his factory once housed an abattoir. They had no clue that the site inspired the title of Kurt Vonnegut’s novel “Slaughterhouse-Five.”

By the time I returned to America in the mid-2000s after assignments in Russia and Germany, American marketers were harnessing the power of big data to assemble millions of dossiers. They didn’t need spies in the field, just computers recording data. They knew something about almost everyone, famous or obscure.

Such easy information made reporting easier. I could find Major League Baseball Hall of Famers such as Willie Mays or Yogi Berra to talk about the sports steroid scandal.

When Gerald Ford died, I reached Chevy Chase, via his daughter’s cell phone. He recalled the day he spent with the former president. Later, he called back to stress that his mockery of Ford on “Saturday Night Live” had not cemented his career as I had suggested. Then he got to what was really bothering him: how the hell did I find his daughter’s number?

I began to wonder: Who were the people behind the companies gathering personal information about everyone? How did they obtain their data? And what impact does the easy availability of personal information have?

The result is my book “What Stays in Vegas: The World of Personal Data—Lifeblood of Big Businesses—and the End of Privacy as We Know It,” published in September by PublicAffairs.

Much of the narrative takes place in Las Vegas, a setting that helps bring the potentially dry subject of data alive. More people are married there than anywhere else, creating public records at the heart of commercial data dossiers. And more private cameras watch inside casinos than anywhere else.

Working in Russia and Eastern Europe proved to be great training for prying into the secretive world behind the data curtain. As in post-Communist Russia and Eastern Europe, data has created a world of opportunities and peril.