View photos below »My father introduced his seven-year-old son to international politics in the cosy environs of a provincial Greek pizza joint. It was the mid-1980’s, and the Iran-Iraq War was in full swing. The mud-drenched battlefields of western Iran appeared impossibly faraway to my childish mind. They were Hobbesian landscapes, on which tens of thousands of people sacrificed themselves in epic offensives that seesawed a few meters back and forth over slowly decomposing bodies across a disputed border.

While the steaming slice of pizza on my plate appeared decidedly more captivating than relentless slaughter in the name of Islam or Arab nationalism, one of the things my father told me that day stuck. An evening news report about the war flickering in the background must have prompted him to introduce me to the concept of hypocrisy. The example he used was the just-erupted Iran-contra affair, in which Washington and Tel Aviv had armed both sides with low-tech weaponry designed to maximize the slaughter and prolong the stalemate. I remember that not even the taste of the delicious pizza could obscure the shock I felt at this revelation.

RELATED WEB LINK

On the 30th anniversary of Iran’s Islamic revolution, Iason Athanasiadis’ gallery of photographs of Iranian society appeared in The Guardian. View his gallery here » More than 20 years have passed since then. I grew up, studied Arabic, and began covering the Middle East. The immediate consequence of this career choice was the loss of any vestigial traces of innocence. Now, every time I return to Greece, I feel more disconnected to an ever wealthier, ever more carefree society that looks only Westwards as it drifts apart from the realities of its neighborhood.

“Don’t become a journalist,” one unmarried, 50-something British correspondent advised me on a Greek summer afternoon as I was just starting out on my career. “You’ll make no money, have no stability, and a terrible personal life.”

He was right on all counts. But there are few more challenging or rewarding occupations than covering the Middle East as a freelance journalist. That the world’s premier news-producing region is also among the most misunderstood and misrepresented is not so much a Western conspiracy, as public opinion would have it in the Arab or Persian street, but rather reflects its seemingly infinite layers of complexity. In an area whose cultural norms often appear diametrically opposed to the West and where the barriers of language and culture are almost insurmountable, I often found that simple images told the story more effectively than sentences encumbered by qualifications, complicated by parentheses, and clogged by background. My outsider’s eye saw distinguishing details that local familiarity overlooked, while living in the region enabled me to recognize the images that count and capture them.

In the Middle East, the work of Western journalists is further complicated by across-the-board official and popular suspicion. Much of the blame must be shouldered by Middle Eastern governments. An official in the press ministry of one of the region’s most difficult-to-access countries minced no words in telling me that visiting Western journalists without fluency in Persian or a deep understanding of the culture are preferable to foreigners who have attained insider knowledge. The revelation was offered after that country’s intelligence ministry vetoed my sixth application for a press residency, and the official took pity at my despair. At a dinner party, a local analyst for a Western embassy explained that the government feared the “cultural intelligence” that journalists provide on the societies they write for—exactly the charge on which Canadian-Iranian intellectual Ramin Jahanbegloo was jailed for after it was discovered that an American NGO commissioned him to create a map of his country’s civil society.

Being Greek—In the Middle East

Ever since studying Arabic and making the region my beat, my focus has been to live within the societies I report on and express their peoples’ realities, rather than cover the choreographed, sometimes delusional public relations ploys of some of the planet’s more autocratic politicians. Being Greek makes me a quasi-insider: We have been present as a regional power from antiquity through to the Byzantine Empire. Later, as Christian subjects of the Muslim Ottoman Empire, the Greeks were its bankers, merchants and diplomats to the European West.

The switch of allegiances to the West only came in the 19th century, after the Great Powers helped Greece win its War of Independence. There is still residual mistrust over the Crusaders’ sacking of Constantinople on their way to Jerusalem and the lack of help sent by Genoa as the Turks scaled the capital of Byzantium. After World War II, Greece remained firmly within the Western orbit and became the first line of defense against the Soviet Union. In the post-9/11 world, Greek politicians have continued the tradition of the intermediary, most notably when former Greek foreign minister and Colin Powell confidante George Papandreou passed messages from the Bush administration to the Taliban prior to their overthrow. Greek construction companies were trusted by Arab leaders to construct much of the Gulf’s infrastructure, build clandestine military bases in Libya, and erect palaces in Saudi Arabia complete with secret escape routes in case of an antimonarchical revolution.

A fine example of the “intermediary Greek” is that country’s current ambassador to Baghdad. Panayiotis Makris was educated in Alexandria’s Victoria College, speaks fluent Egyptian Arabic, packs a pistol in his leather briefcase, and lives resolutely outside the Green Zone. A 17th century tapestry depicting Alexander the Great’s death in Babylon dominates his living room in the kidnapping-scarred diplomatic district of Mansour. His professional performance is likewise infused with an historical perspective. As he points out to visitors, Alexander died just 10 kilometers from Baghdad; “We’re the only country that has the right to offer lessons in democracy around here,” he quips in a barely concealed barb at the American mismanagement of their Iraq occupation.

Greece’s man in Tehran similarly draws heavily upon history in his dealings with Iranian officials. His enthusiastic and repeated claims that Greece and Iran share 5,000 years of shared civilization may owe more to Athens’ dependence on Iranian oil imports and an innate proclivity to exaggerate than to historical fact. But the excellent ties between Greece and Iran reveal how important a shared cultural background is to a bilateral relationship.

When I was a child in Athens, my mother would lull me to sleep with stories from the “1001 Nights.” Today I live in the territories that inspired these myths, and their politics are no less complicated or treacherous. RELATED WEB LINK

“Persian Culture and Iran’s Defiant Diplomacy”

–worldpoliticsreview.comThough the stories I contribute from the Middle East are decidedly less fairytale-like than the adventures of Sabah the Sailor, my work is well done if they go at least some way towards furthering mutual understanding.

Iason Athanasiadis, a journalist based in Tehran, will be a 2008 Nieman Fellow. He has written for The Christian Science Monitor, the Financial Times, the International Herald Tribune, the Sunday Telegraph, The Guardian, the Toronto Star, The Washington Times, and Australia’s leading current affairs magazine The Diplomat. His March 2007 article, “Persian Culture and Iran’s Defiant Diplomacy: A View from Tehran,” can be read on the World Politics Review Web site.

Two men smoke narghileh under faded posters depicting assassinated former Lebanese Premier Rafik Hariri and his son Saad in the port city of Tyre a few days after the end of the 2006 Summer War. Photos by Iason Athanasiadis.

A girl who returned to her house in the village of Aita Shaab, Lebanon, surveys the damage.

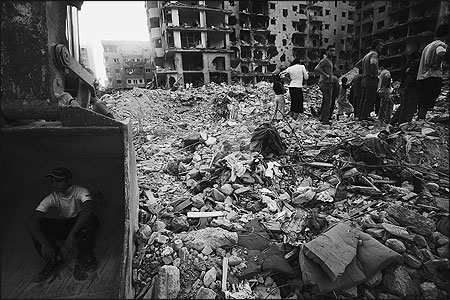

A Shi’ite youth plants the Hizbullah flag and rests the Shi’ite Zulfikar Scimitar upon the rubble of the Shi’ite-majority al-Dahieh suburb of Beirut.

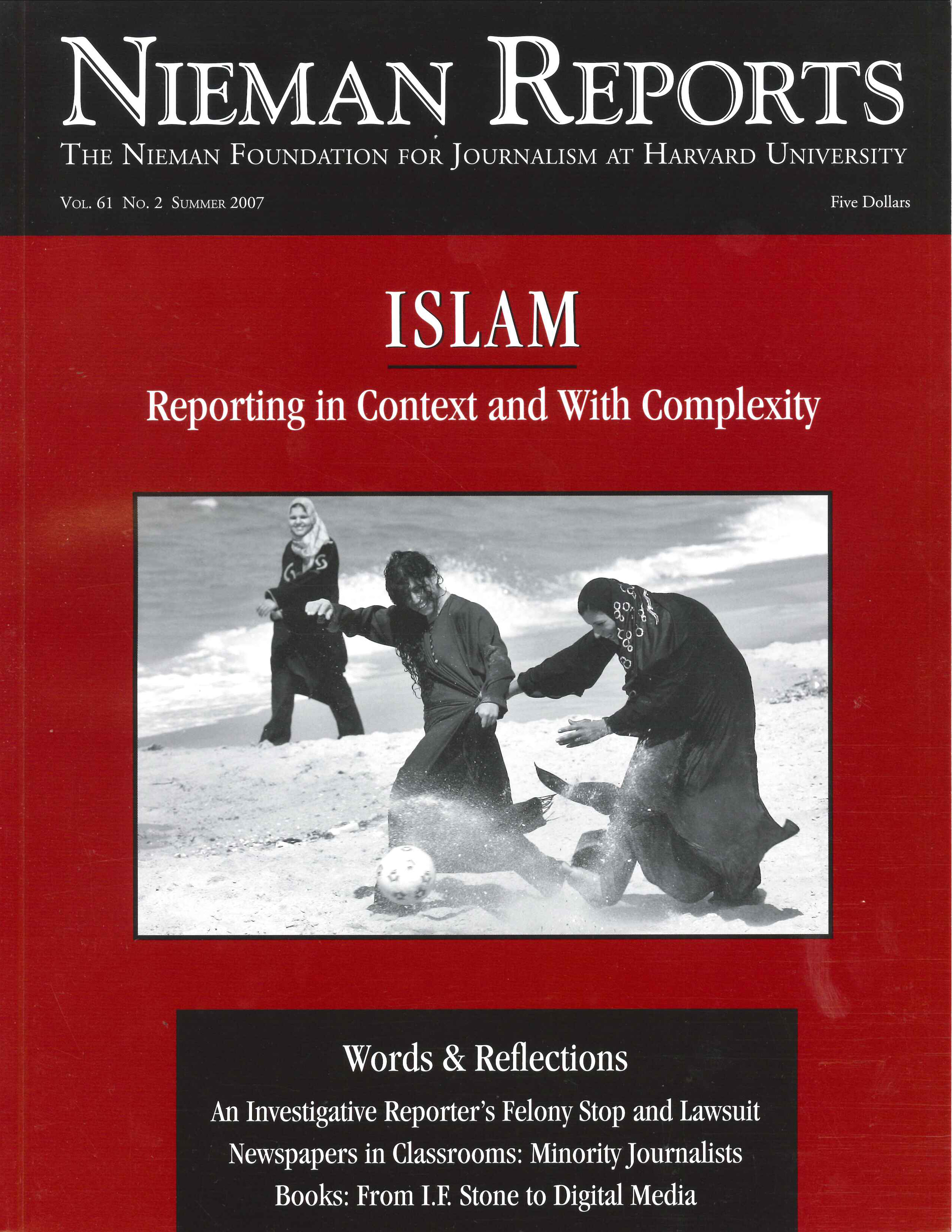

Kurdish muhboland (long-haired) Sufis in mid-zikr in Iranian Kurdistan.

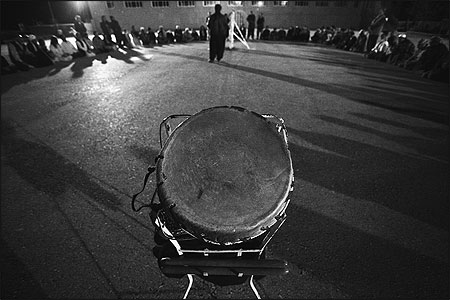

Bathed with light from tall stadium lights, Casnazani Sufis take a rest after the zikr ceremony in their military base-like khaneqah in Northern Iraq.

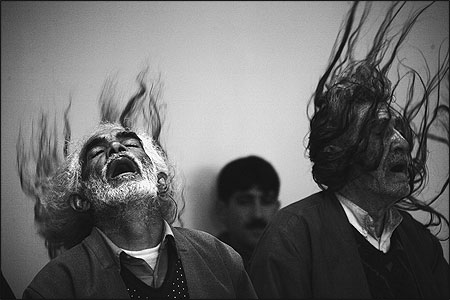

The African-like drum is pounded during the ceremony to create the mesmerizing rhythm of the zikr, a remembrance of Allah (God) through verbal and mental repetition of His divine attributes.

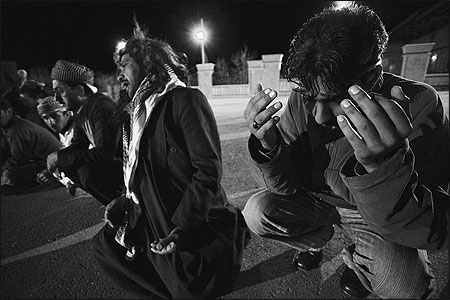

At the end of the zikr ceremony, Casnazani Sufis offer final obeisances.

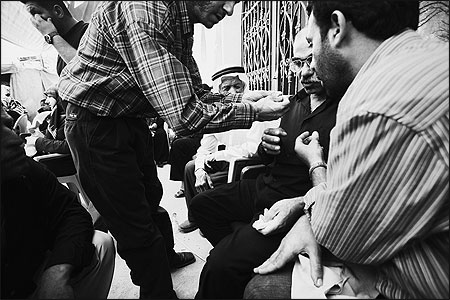

Hizbullah volunteers in a Shi’ite-majority village in the south tell a bereaved father that his missing son was a fighter martyred in action.

A Shi’ite youth sits in the scoop of a rubble remover on the afternoon of the cease-fire in the 2006 Summer War in Lebanon.