From the beginning, minority communities in California, which by now are the majority of the state’s population, were not part of the movement toward the governor’s recall election, the tremor that shook the Golden State with a force reminiscent of periodic movements of the San Andreas Fault. The decisions involved in the recall of Governor Gray Davis emerged from a small but dedicated group of conservative activists and were later fueled by the suburban voter who worries about raising taxes and the proliferation of benefits for those less fortunate, including the largely faceless group referred to as “those illegal aliens.”

This pattern is in keeping with Ronald Reagan’s election as governor in the 1960’s, passage of the anti-tax Proposition 13 during the 1970’s, and the voters imposition of term limits in the early 1990’s. Voter revolts haven’t come from the less affluent and expanding minority communities where economic downturns mean loss of jobs, cuts in pay, closure of neighborhood health clinics, and anti-immigrant initiatives. They arise out of the anger of the mostly white middle class.

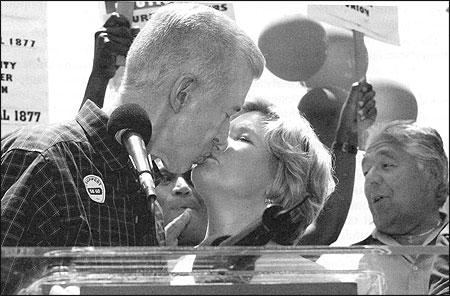

Governor Gray Davis kisses his wife at a political rally. Photo by Ciro Cesar/La Opinión.

Informing Potential Voters

So it became our job, as journalists from the state’s only Spanish daily newspaper, not only to inform our community about developments in this fast-paced political story but also to try to explain this odd election to our readership. Most of our readers had no knowledge of the recall process. Is there relevant historic precedent? How will the election work? What happens next? Those who rely on us for news include a mix of recent immigrants, new voters, and older generation Latinos who’d never seen anything like this kind of political maelstrom and wondered how, in the end, this unique election might affect them. As the campaigns got underway, they also wondered whether it would devolve into a circus or showcase democracy in action. What choices would they have as voters?

Besides following the candidates, we struggled to explain what these campaigns were about. We dedicated a great part of our reporting resources to civic journalism, which is often a strategy used by newspapers that serve immigrant communities. By taking this approach, we are able to inform, explain, interpret and, at times, advocate for the interests of our readership. In this election cycle, we found this harder to do; even the experts often didn’t know answers to our questions.

To help bring the community in tune with the developing political dynamic, we did some things we had tried during previous elections. We went out on the street and invited people to pose questions to candidates, which we used in our reporting on particular issues. We’d do articles explaining how the election would work—explaining what it is, its process and history. We encouraged political participation by letting our community members understand what was at stake for them in this election, pointing out the need to vote and reminding them of key dates for registering, requesting absentee ballots, and other details related to voting.

Journalist as Spokesperson

In my job as political editor for La Opinión, I was pushed to do more than just report, write, plan coverage, and edit—all of which I normally do each day given the smaller size of our paper. In addition to these roles, I became a source for other journalists, as more and more called to interview me. They were trying to better understand Latinos and to explain us, as Americans, to Spanish-speaking audiences throughout the world. Though this happens during every political campaign, the interviewing demands on me were especially intense during this election, and the time I spent doing them, of course, took away from my own reporting and editing hours.

But I recognize that wearing this other hat—and becoming a source of news—is now part of my job. Other journalists want me to present the Latino perspective on news shows; often I am asked to express the thoughts, feelings or trends in the Latino community, as if I can represent the thoughts and feelings of this large and diverse group. “What do Latinos think about this election?” I am asked repeatedly. Most of the time, such questions strike me as funny, because I’ve never seen a colleague of the mainstream media being asked, “What do Anglos think about this?”

While I understand that these reporters come to journalists like me because we are viewed as “experts,” I often wish they would go out into the communities themselves and find out on their own about what issues the people care about and why. It makes me realize that the lack of a strong Latino presence in newsrooms of most mainstream publications presents a handicap to these news organizations.

Still, I try to explain to these reporters what I know as best as I can. I look at this as an opportunity to represent my newspaper in front of a different and broader audience. And I use these platforms to try to foster understanding about the political, social or economic realities in the Latino community. What I find is that the mainstream population has very little understand-ing—beyond its usual stereotypes—of what certain groups of people are like who live only blocks away from them.

With Arnold Schwarzenegger’s entrance into the campaign, huge interest developed worldwide about the political process in California. Along with other colleagues at the newspaper, I received interview requests from reporters in Latin America, Spain and other countries in Europe, including the BBC’s world service in Spanish. My ability to speak Spanish and English and firsthand knowledge of the story made me a valued source.

With these reporters I struggled to explain that, in spite of the entertainment quality of the story and insistence by some that this was a circus, not a serious election, this was a very serious, legally sanctioned political event that would have real consequences for real people.

I was also invited to serve on the panel of journalists that conducted the candidate’s first debate in San Jose, California. There I worked with other political editors and reporters to prepare questions and topics for discussion. As a Latina journalist, my perspective generated a few questions about social and economic issues of particular interest to the Spanish-speaking community I serve. Because Schwarzenegger did not show up for this debate, we were not able to get his perspective on these issues.

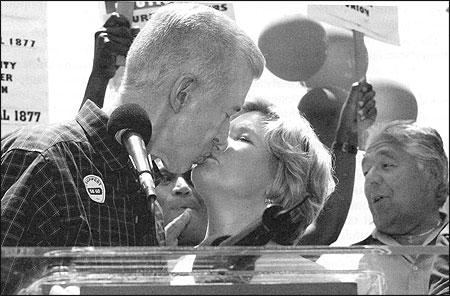

Former President Bill Clinton and Lt. Governor of California, Cruz Bustamante, greet crowds at the inauguration of a new school named after Clinton. Photo by J. Emilio Flores/La Opinión.

The Immigrant Connection

In California, the related topics of immigration and demographic changes find their way to the fore of nearly every political debate, and this recall election proved to be no different. At La Opinión, two major angles of coverage for our readers emerged early in the campaign: Lieutenant Governor Cruz Bustamante, who became the Democrat’s alternative candidate in the recall of the governor of his own party, is the first Latino to be the gubernatorial candidate of a major party in modern California history. And, in an effort to win over Latino voters, Davis signed controversial legislation favored by Latino activists and unions to provide undocumented immigrants with the possibility of obtaining driver’s licenses.

Bustamante’s campaign proved to be lackluster, and his candidacy’s purpose was hard for people to understand because of his politically complicated message of “No on the recall, Yes on Bustamante.” With this campaign, there turned out to be very little to cover after an initial surge and a couple of good proposals. Instead, the dynamic of the campaign started to revolve around how Schwarzenegger would “terminate” Davis.

The issue of permitting undocumented immigrants to get licenses is a story we’re still covering. The bill, signed by Governor Davis in early September, would benefit an estimated one to two million people, but by becoming law it enraged a majority of the state’s population, many of whom associate issues involved in immigration with their concerns about terrorism and porous boundaries. Right now, there are referendums and initiatives under way that target the driver’s license bill and other benefits for immigrants, as anger generated by a bad economy turns against certain populations. [The drivers license bill was repealed in November.]

Because La Opinión is a newspaper read by a Spanish-speaking audience, we will closely monitor what happens with these issues and do so more closely than most mainstream publications. And the perspective of our coverage will also be different, since we will definitely look favorably on immigrants’ rights. We know our readership and why they’ve come to this country. This same perspective is found among the journalists who work for La Opinión. The majority of them are immigrants, and they bring their own life experiences to their coverage of these issues. There is no doubt that inflammatory immigrant issues, such as this one, will continue to be a large part of our political coverage during the months ahead and probably into the presidential campaign. In some ways, this is a legacy of this odd political process we’ve just endured. In other ways, it is simply a reminder that the more things change, the more they remain the same.

Pilar Marrero is political editor and columnist for La Opinión newspaper in Los Angeles, California.

This pattern is in keeping with Ronald Reagan’s election as governor in the 1960’s, passage of the anti-tax Proposition 13 during the 1970’s, and the voters imposition of term limits in the early 1990’s. Voter revolts haven’t come from the less affluent and expanding minority communities where economic downturns mean loss of jobs, cuts in pay, closure of neighborhood health clinics, and anti-immigrant initiatives. They arise out of the anger of the mostly white middle class.

Governor Gray Davis kisses his wife at a political rally. Photo by Ciro Cesar/La Opinión.

Informing Potential Voters

So it became our job, as journalists from the state’s only Spanish daily newspaper, not only to inform our community about developments in this fast-paced political story but also to try to explain this odd election to our readership. Most of our readers had no knowledge of the recall process. Is there relevant historic precedent? How will the election work? What happens next? Those who rely on us for news include a mix of recent immigrants, new voters, and older generation Latinos who’d never seen anything like this kind of political maelstrom and wondered how, in the end, this unique election might affect them. As the campaigns got underway, they also wondered whether it would devolve into a circus or showcase democracy in action. What choices would they have as voters?

Besides following the candidates, we struggled to explain what these campaigns were about. We dedicated a great part of our reporting resources to civic journalism, which is often a strategy used by newspapers that serve immigrant communities. By taking this approach, we are able to inform, explain, interpret and, at times, advocate for the interests of our readership. In this election cycle, we found this harder to do; even the experts often didn’t know answers to our questions.

To help bring the community in tune with the developing political dynamic, we did some things we had tried during previous elections. We went out on the street and invited people to pose questions to candidates, which we used in our reporting on particular issues. We’d do articles explaining how the election would work—explaining what it is, its process and history. We encouraged political participation by letting our community members understand what was at stake for them in this election, pointing out the need to vote and reminding them of key dates for registering, requesting absentee ballots, and other details related to voting.

Journalist as Spokesperson

In my job as political editor for La Opinión, I was pushed to do more than just report, write, plan coverage, and edit—all of which I normally do each day given the smaller size of our paper. In addition to these roles, I became a source for other journalists, as more and more called to interview me. They were trying to better understand Latinos and to explain us, as Americans, to Spanish-speaking audiences throughout the world. Though this happens during every political campaign, the interviewing demands on me were especially intense during this election, and the time I spent doing them, of course, took away from my own reporting and editing hours.

But I recognize that wearing this other hat—and becoming a source of news—is now part of my job. Other journalists want me to present the Latino perspective on news shows; often I am asked to express the thoughts, feelings or trends in the Latino community, as if I can represent the thoughts and feelings of this large and diverse group. “What do Latinos think about this election?” I am asked repeatedly. Most of the time, such questions strike me as funny, because I’ve never seen a colleague of the mainstream media being asked, “What do Anglos think about this?”

While I understand that these reporters come to journalists like me because we are viewed as “experts,” I often wish they would go out into the communities themselves and find out on their own about what issues the people care about and why. It makes me realize that the lack of a strong Latino presence in newsrooms of most mainstream publications presents a handicap to these news organizations.

Still, I try to explain to these reporters what I know as best as I can. I look at this as an opportunity to represent my newspaper in front of a different and broader audience. And I use these platforms to try to foster understanding about the political, social or economic realities in the Latino community. What I find is that the mainstream population has very little understand-ing—beyond its usual stereotypes—of what certain groups of people are like who live only blocks away from them.

With Arnold Schwarzenegger’s entrance into the campaign, huge interest developed worldwide about the political process in California. Along with other colleagues at the newspaper, I received interview requests from reporters in Latin America, Spain and other countries in Europe, including the BBC’s world service in Spanish. My ability to speak Spanish and English and firsthand knowledge of the story made me a valued source.

With these reporters I struggled to explain that, in spite of the entertainment quality of the story and insistence by some that this was a circus, not a serious election, this was a very serious, legally sanctioned political event that would have real consequences for real people.

I was also invited to serve on the panel of journalists that conducted the candidate’s first debate in San Jose, California. There I worked with other political editors and reporters to prepare questions and topics for discussion. As a Latina journalist, my perspective generated a few questions about social and economic issues of particular interest to the Spanish-speaking community I serve. Because Schwarzenegger did not show up for this debate, we were not able to get his perspective on these issues.

Former President Bill Clinton and Lt. Governor of California, Cruz Bustamante, greet crowds at the inauguration of a new school named after Clinton. Photo by J. Emilio Flores/La Opinión.

The Immigrant Connection

In California, the related topics of immigration and demographic changes find their way to the fore of nearly every political debate, and this recall election proved to be no different. At La Opinión, two major angles of coverage for our readers emerged early in the campaign: Lieutenant Governor Cruz Bustamante, who became the Democrat’s alternative candidate in the recall of the governor of his own party, is the first Latino to be the gubernatorial candidate of a major party in modern California history. And, in an effort to win over Latino voters, Davis signed controversial legislation favored by Latino activists and unions to provide undocumented immigrants with the possibility of obtaining driver’s licenses.

Bustamante’s campaign proved to be lackluster, and his candidacy’s purpose was hard for people to understand because of his politically complicated message of “No on the recall, Yes on Bustamante.” With this campaign, there turned out to be very little to cover after an initial surge and a couple of good proposals. Instead, the dynamic of the campaign started to revolve around how Schwarzenegger would “terminate” Davis.

The issue of permitting undocumented immigrants to get licenses is a story we’re still covering. The bill, signed by Governor Davis in early September, would benefit an estimated one to two million people, but by becoming law it enraged a majority of the state’s population, many of whom associate issues involved in immigration with their concerns about terrorism and porous boundaries. Right now, there are referendums and initiatives under way that target the driver’s license bill and other benefits for immigrants, as anger generated by a bad economy turns against certain populations. [The drivers license bill was repealed in November.]

Because La Opinión is a newspaper read by a Spanish-speaking audience, we will closely monitor what happens with these issues and do so more closely than most mainstream publications. And the perspective of our coverage will also be different, since we will definitely look favorably on immigrants’ rights. We know our readership and why they’ve come to this country. This same perspective is found among the journalists who work for La Opinión. The majority of them are immigrants, and they bring their own life experiences to their coverage of these issues. There is no doubt that inflammatory immigrant issues, such as this one, will continue to be a large part of our political coverage during the months ahead and probably into the presidential campaign. In some ways, this is a legacy of this odd political process we’ve just endured. In other ways, it is simply a reminder that the more things change, the more they remain the same.

Pilar Marrero is political editor and columnist for La Opinión newspaper in Los Angeles, California.