When Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Jeff Gammage writes an article on the immigration beat, he often thinks about the history of the city he covers.

Philadelphia, the first U. S. capital, has always been a city of immigrants, from Germans in the 17th century to Koreans in the 20th century. Gammage would love to get more historical context into his work, but it’s difficult under the pressure of daily deadlines and hourly tweets. He hopes that a new partnership between Inquirer journalists and local historians will help.

“Even when I was a young reporter covering city council meetings, I’d think, ‘This didn’t just spring out of thin air. A whole host of things happened to bring us to this moment,’” he says. “I try to think of all my stories that way: How did we get here? And what does the past have to say about the present?”

To try to answer these kinds of questions in daily journalism, the Inquirer has teamed up with Villanova University’s Albert Lepage Center for History in the Public Interest and the Lenfest Center for Cultural Partnerships at Drexel University under a grant from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, the nonprofit group that owns the Inquirer. The pilot program focused on three areas of coverage—infrastructure, immigration, and the opioid crisis—that could benefit from a historical perspective. The collaboration will continue this year. A December 2019 meeting focused on topics such as the 2020 presidential election and the U.S. Census.

“We’re at a very extraordinary time in American history, where agreeing to a common set of facts has become very difficult,” says Stan Wischnowski, the Inquirer’s executive editor. “When you combine high-impact journalists—with great track records of being accurate, fair, and thorough—with historians trained to dig up factual information, the driving force is getting to those common sets of facts in a way that makes it very clear to our audience that they can trust what we’re saying.”

The Lepage project highlights a growing acknowledgment that journalists and historians toil in the same field, although with different goals and perspectives

The Lepage project highlights a growing acknowledgment that journalists and historians toil in the same field, although with different goals and perspectives. Journalists write the “first rough draft of history,” according to the aphorism often attributed to Washington Post publisher Philip Graham. The historian’s task is to dig deeper and uncover the larger trends and consequences of historical events. But journalists also need to incorporate more history into their reporting to counteract the hype of partisan politics, amplified by social media’s emphasis on the immediate and the inflammatory. Hot takes can’t handle the backstory of history. Moreover, as traditional history education wanes, more academics see the value of cooperating with journalists to participate in the public sphere. A historical perspective can add clarity and context to current events.

In fact, historians who do interviews with reporters eager for context—or who write non-academic pieces for mainstream publications—may be offering the only history lessons many people receive. A 2018 report by Northeastern University history professor Benjamin M. Schmidt confirmed a worrying trend: since the 2008 economic crisis, history has seen the steepest decline in majors, despite increased college enrollment overall. Jason Steinhauer, the Lepage Center’s director, says bringing history to bear on contemporary issues is part of the center’s mandate and often “that happens through the press, mediated by journalists.”

At a June meeting, Inquirer journalists and eight historians from local universities—including Villanova, the University of Pennsylvania, and Drexel—agreed on topics that had “resonances nationally and impact locally.” The two groups sought to understand each other’s professional exigencies. The scholars saw the deadline and economic pressures that journalists face, while the journalists came to appreciate the scholars’ pressures to publish and teach. They also acknowledged each other’s strengths: journalists respect historians’ depth of knowledge, while historians benefit from journalists’ ability to explain things for popular consumption. “Historians are eager to have their expertise and views inserted into the public discourse,” says Steinhauer, who is a public historian with a specialty in history communication.

The journalists left with expanded source lists and a sense that their beat knowledge combined with the historians’ expertise could lead to stronger coverage, something often missing in the 24/7 news cycle. “Journalists have been using historians as sources for a long time,” Wischnowski says. “The challenge going forward will be: Can we maintain a cadence that serves the needs of news organizations?”

Iris Adler, the executive director for programming, podcasts, and special projects, at Boston public radio station WBUR, decided to create a history-infused podcast after the election of Donald Trump. On the eve of the January 2017 inauguration, she attended a discussion on “opportunities and challenges for the new administration” at Boston’s John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Among the panelists were Ron Suskind, the Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, and Heather Cox Richardson, a professor of history at Boston College. They discussed the election and what it meant in terms of American history. She liked the way Richardson took the long view, back to the 1800s, and how Suskind expounded on more recent presidential history.

Adler asked them to team up to create “Freak Out and Carry On,” a 2017-18 WBUR public radio podcast. “With the luxury of the haIf-hour format, and not a four-minute report, we had a chance to maybe choose one or two things that happened in the week, and take a deep dive,” Adler says.

In June 2017, Suskind introduced listeners to the show this way: “Welcome to the new politics and history podcast that asks, ‘What is happening? And has it happened before?’” Then, Richardson added: “I wanted to do this podcast because when I read news about the Trump administration’s actions, it always frustrates me when it seems like journalists have no concept of what happened before—about a minute and a half ago.”

In the show, Suskind went on to say that stepping back from the daily grind is more important than ever: “Right now journalists are often filing two or three times a day, and that’s not going to work in terms of giving people a sense of what’s really going on.” Richardson added that context is particularly important because the country is at a pivotal moment: “We are watching Americans re-examine the basic principles of the American government.” She cited other such moments: the American Revolution, the Civil War, the New Deal, and the Reagan Revolution.

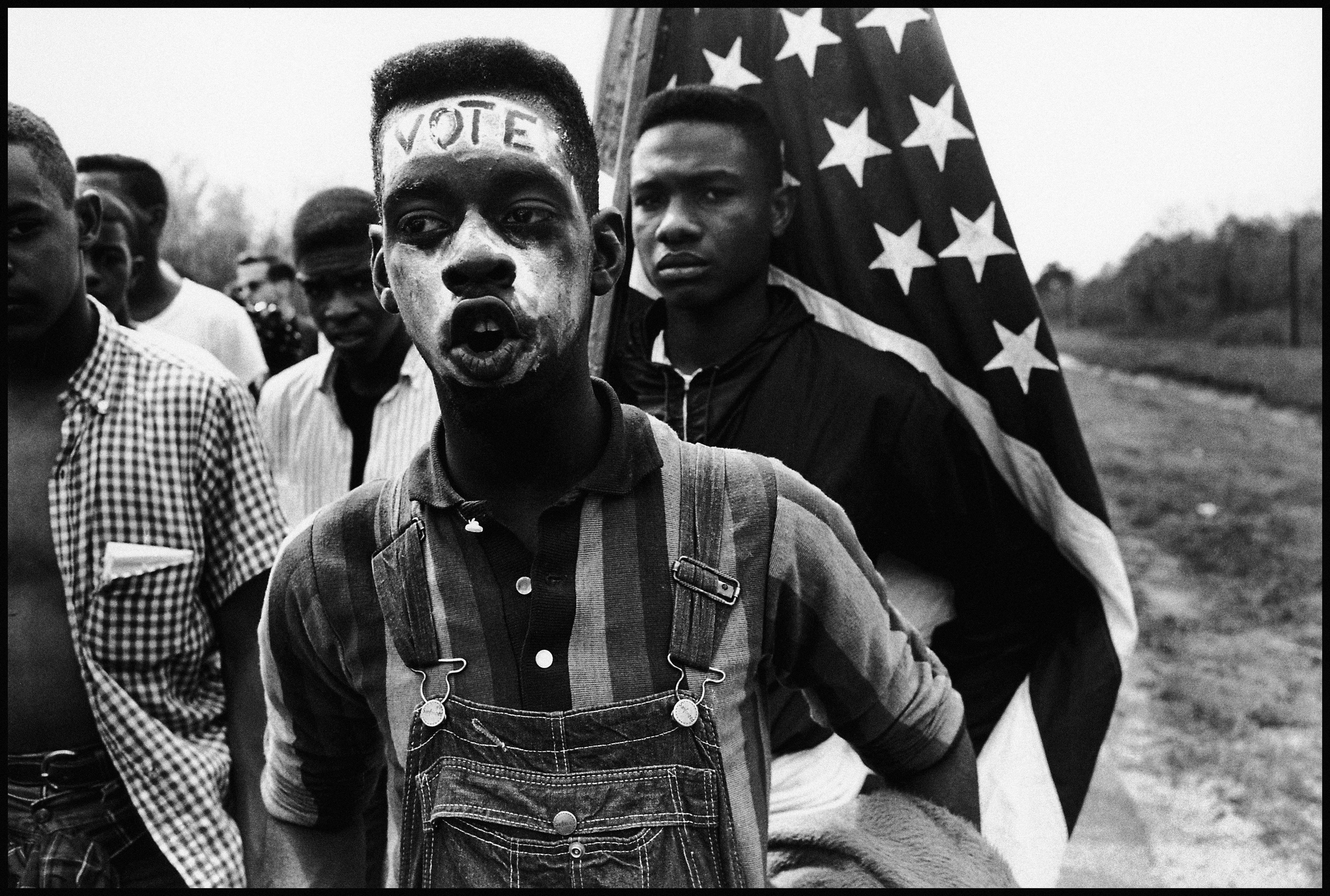

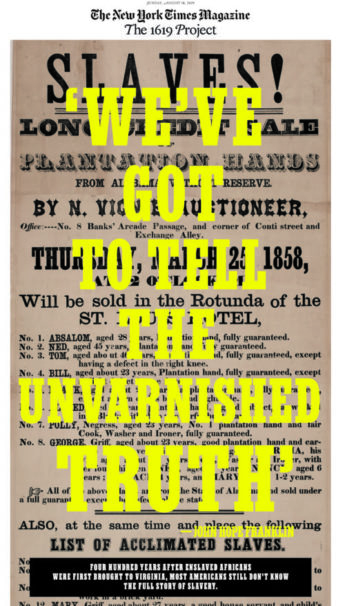

The groundbreaking New York Times “The 1619 Project” demonstrates the potential of collaborations between journalists and scholars

To understand how the Trump presidency fit into this progression, Suskind and Richardson discussed issues such as Trump’s firing of FBI director James Comey and the violent white nationalist and neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, in which a young counter-protester was killed. An August 2017 podcast episode featured Harvard law professor Randall Kennedy, who writes about the intersection of race and the law, and the late journalist and Civil War historian Tony Horwitz. All agreed that the event was a shocking and watershed moment in American history. The white nationalists were protesting the removal of Confederate statues by marching with torches through Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia, and shouting “Jews will not replace us.”Richardson suggested that the incident linked Confederate monuments with neo-Nazism for the first time in American history, while Horwitz said that it laid to rest the post-Civil War whitewash of the pro-slavery Confederacy as a “heritage” movement.

Later, reflecting on the year-long podcast, Suskind says they were trying to tell listeners, “Here’s what you’re seeing. Here’s where it fits into the American firmament and here’s how you ought to think about this.” After the podcast ended, Richardson used Facebook posts and a free daily newsletter to continue to broadcast her take on breaking news. Richardson says she started the Facebook “diary” in fall 2019 on a professional page that had 22,000 followers. Two months later, in November, it had more than 125,000. “In my field we’re really good at research and what we study is how societies change,” Richardson says. “We’re good at theory … Journalists are good at catching an audience … It’s important that we work together and combine our skill sets.”

The groundbreaking New York Times “The 1619 Project” demonstrates the potential of collaborations between journalists and scholars. It reframed American history by making a provocative assertion: The year that the first slave ship arrived in the English colonies marks the true year of the nation’s founding.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, a New York Times Magazine staff writer and the driving force behind the project, recruited a wide-ranging group of historians as she developed her idea and pitched it to editors. The project, which consisted of a special issue of the magazine and a corresponding special section of the newspaper, was published in August 2019, on the 400th anniversary of the year a ship called the White Lion arrived in Virginia carrying 20 to 30 enslaved Africans. The special issue documented the many ways that slavery’s legacy has permeated contemporary American life. It contained history-infused explorations of traffic jams and health care, and even an analysis of the link between slavery and “the sugar that saturates the American diet.” Along with historians and academics, Hannah-Jones recruited poets, playwrights, and novelists to illustrate how black resistance to slavery and racism spurred progress and equality for all Americans.

Hannah-Jones says she was actually looking for a low-key assignment when she pitched the idea a few days after returning from a leave to write a book, which still needed her attention. But she knew that the anniversary, which wasn’t well-known, was approaching and “it seemed like a duty and an opportunity to write about it,” she says.

Once her editors green-lighted the project as a special issue, she reached out to 18 scholars to brainstorm with editors. About a dozen agreed to participate. “Any work of journalism that is trying to be big and important to some degree, has to understand the history of how we got here,” says Hannah-Jones, who received a MacArthur “genius” grant in 2017. “The absence of that history is the absence of the ability to tell the whole story, to give readers the full context of what’s going on right now.”

The special sections sold out on the day they were put online in the NYT Store, with a waiting list of 30,000 people. The Times recently released more copies which are still selling. In addition, the paper turned the project into a school curriculum in cooperation with the Pulitzer Center. Books are also in the works. The outsized reaction was mostly positive, although some conservatives criticized it and some scholars found its approach reductionist. In December, the Times printed a letter to the editor from five prominent historians who questioned the accuracy of some of the project’s central facts and requested corrections. The historians maintain that the nation’s founders did not, as the 1619 Project’s lead essay by Hannah-Jones states, declare independence from Britain “in order to ensure slavery would continue.” They also take issue with the claim that “for the most part,” black Americans have fought their freedom struggles “alone” and they called the description of Abraham Lincoln’s views on racial equality “misleading” because it “ignores his conviction that the Declaration of Independence proclaimed universal equality, for blacks as well as whites.” In a lengthy response, Jake Silverstein, The New York Times Magazine’s editor-in-chief, declined to issue corrections and characterized the disagreement as a debate among scholars about how to see the past. He notes that the paper intends this year to host public conversations “among academics with differing perspectives on American history.”

Silverstein says it’s not the first time the magazine has published a special section steeped in history. In August 2018, the magazine published “Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change,” which he describes as “a work of historical investigative journalism.” The narrative by Nathaniel Rich addressed the years from 1979 to 1989, when the causes and dangers of climate change became widely known. Current aerial photographs were juxtaposed with the written history to further understanding of how the world failed to act on climate change at a pivotal time.

But nothing has come close to the reception that “The 1619 Project” has received. “It hit a nerve because it was surprising to a lot of people, even well-educated people who think of themselves as enlightened,” Silverstein says. “We’ve heard from so many people who say, “Wow, I didn’t know this.’”

Elena Gooray, The Philadelphia Inquirer’s opinion coverage editor, found the project useful as inspiration for an idea that arose in collaboration with the Lepage Center. She asked four scholars to answer the question: “Where does the American story begin?”

The September 15, 2019 editorial page, pegged to an upcoming Lepage Center public event on “Revisionist History,” contained four 300-word answers from historians from Villanova University, Philadelphia’s Museum of the American Revolution, the College of William & Mary, and Howard University. Gooray says she has never before worked on a package so steeped in history since joining the paper in November 2018: “One of my goals in this collaboration was to produce content that engages readers and gives them a bit of insight into the process of writing history.”

“Making sense of the present by revealing the past” is the tagline of the PBS Retro Report

Still, journalists must beware of the pitfalls of viewing historical events and documents through a modern-day lens. “They don’t get the language of the past, so they can make a bad mistake,” Richardson says. The most prominent recent example has been Naomi Wolf’s book “Outrages: Sex, Censorship and the Criminalization of Love,” an examination of Victorian laws surrounding same-sex relations. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt cancelled publication after it was revealed in a BBC interview that Wolf mistakenly asserted that she had found evidence of “several dozen executions” of men accused of having sex with other men. It turns out she misunderstood the legal term “death recorded,” which actually means that the men had been pardoned.

“Making sense of the present by revealing the past” is the tagline of the PBS Retro Report, a public television series that debuted in October. The show is the latest project from retroreport.org, a nonprofit that produces short-form documentaries exploring the recent history behind current events. The nonprofit has also partnered with other news organizations such as The New York Times, Politico, and The Atlantic. The PBS show, hosted by journalist Celeste Headlee and actor-artist Masud Olufani, is styled after “60 Minutes,” with three or four short pieces and a comedy kicker by New Yorker humor writer Andy Borowitz.

The show has delved into such diverse topics as why texting may be able to reduce suicide rates, and how a well-known court case still shapes surrogate parenthood. The segment on rising suicide rates explored how a current program to send short, caring text messages to those at risk echoed a San Francisco psychiatrist’s unusual research experiment in the late 1960s, in which researchers sent caring letters to discharged patients. The patients who received the letters had half the suicide rate of those who hadn’t. The segment on surrogacy retold the controversial case of Baby M, an infant birthed by surrogate mother Mary Beth Whitehead, who then fought to keep her. It is considered the first American court ruling on the validity of a surrogacy agreement, and the piece outlined how its legacy still affects the laws around surrogacy today.

Executive producer Kyra Darnton calls Retro Report’s work “the second draft of history.” The short-form video format, easily shared on YouTube, has the added benefit of being attractive to younger viewers who may not be aware of the context of current events. Although the shorts may feature historians, journalists typically track down participants in prominent episodes from the past to see if their perspectives have changed over time — and to correct the record when necessary.

One short delved into the “myth of the “superpredator”” by interviewing the then-Princeton political scientist who coined the phrase in 1995. John Dilulio, Jr. had predicted an explosion of juvenile crime committed by young people so “severely morally impoverished” they would be capable of profound violence with no remorse. This theory came back to haunt the politicians who espoused it at the time, including both Hillary and Bill Clinton and current Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, because it helped justify harsh policing policies and mass incarceration of young black men. But just as a panic developed, and states began passing tougher laws, juvenile crime rates started plummeting. Social scientists attributed the drop to a variety of factors including a stronger economy, better policing, and a decline in crack cocaine use. Still, it took until 2012 for a public repudiation. In the Retro Report piece, Dilulio, now at the University of Pennsylvania, looks straight into the camera and says “The superpredator idea was wrong. Once it was out there, though, it was out there. There was no reeling it in.” Darnton says the Retro Report’s biggest success comes “when someone involved in an issue says, ‘This is where I was right and this is where I was wrong.’”

Hannah-Jones, who was a daily journalist for much of her career, including stints at The (Raleigh N.C.) News and Observer and the Portland Oregonian, says a beat reporter, whether covering a school board or a foreign war, must incorporate historical context. “Reading history — and writing two paragraphs of historical context in a daily story — is just part of being a good beat reporter, like reading a budget or taking a source to coffee,” she says. Investigative reporters working on prize-winning exposés could also incorporate a historical perspective to give a more systemic look at intractable problems such as segregation. “I definitely think big investigative projects do not do enough of that,” Hannah-Jones says.

Inspired by the Lepage project in Philadelphia, Jennifer Hart, an associate professor who teaches African history courses at Wayne State University, is organizing a series of workshops with news organizations in Michigan. Increasingly, she says, younger scholars who are digital natives acknowledge the power of reaching a wider audience through journalists and through their own public-facing work. Hart maintains a blog called “Ghana on the Go,” which she uses to expound on her area of research expertise, the history and culture of automobile use in Ghana. She also tweets and uses Instagram to showcase her work. Journalists, she adds, must also understand the importance of ensuring that historians get credit for their work when it is cited. With the workshops, Hart wants to create a space where “we could all sit down in the same room, and could talk about best practices, and inform each other how we do our work.”

Jill Lepore, the Harvard American history professor who is also a staff writer at The New Yorker, straddles the line between history and journalism and sees deep differences. “Journalists often take a look at something in the present and go poking around looking for something similar in the past,” she says in an email. “Historians think about structures, and about change over time … Historians think clockwise. Journalists tend to think counter-clockwise.”

Journalists must beware of the pitfalls of viewing historical events and documents through a modern-day lens

Lepore adds that because the two disciplines have such different orientations, journalists should exercise caution when wading into historical analysis. Just like historians, journalists can avoid errors by sticking to basic standards of evidence and argument. Conversely, historians can learn from basic journalistic technique: “…journalists have professional rules, ethical guidelines, for writing about people; historians don’t… Historians tend either to ignore people or to treat them as props.”

Horwitz, who died last May, managed to carve a niche as a kind of hybrid journalist-historian, “equally at home in the archive and in an interview,” as Lepore put it in a remembrance in The New Yorker. He won a Pulitzer Prize for national reporting when he was a Wall Street Journal staff writer, and called his later work as an author “participatory history.” His final book, “Spying on the South,” retraces Frederick Law Olmsted’s route through the South in the 1850s during the years Olmsted wrote dispatches for The New York Times. Horwitz follows his route by taking trains, boats, and even a mule, beginning in Maryland, down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, into Louisiana, Texas and, briefly, Mexico.Using his journalistic skills, he introduces the reader to characters who shed light on the racial and political divide. Using a historian’s perspective, he maps these present-tense scenes onto Olmsted’s observations about the pre-Civil War South. “Tony liked to toggle between now and then … not for forced parallels (always the danger) but for striking, jarring, crucial contrasts,” says Lepore, a former president of Columbia University’s Society of American Historians (SAH), as was Horwitz.

While Horwitz explored “history’s unsettled disputes and unfinished business,” according to a remembrance on the SAH website, Gammage, the Inquirer reporter who was part of a team that won a Pultizer Prize for the paper in 2012, has a more modest goal. He would simply like to have a few reliable historians as sources among his contacts, so that he can give his readers the most accurate representation of the present, informed by the past.

This story has been updated to reflect the length of the Philadelphia Inquirer’s pieces by historians addressing “Where does the American story begin?” and to clarify Elena Gooray’s experience at the Inquirer.