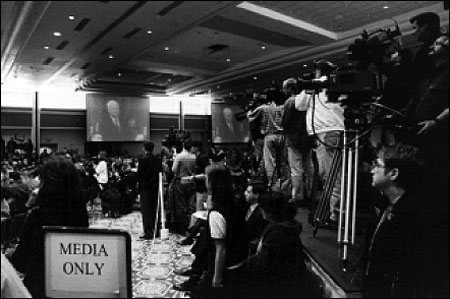

A McCain town hall meeting in Sacramento, California. Photo © Bjorn Brekke/U.C. Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, Center for Photography.

In California, politics is not a contact sport. Interest in presidential politics ranks somewhere below soccer in a roster of civic concerns. Even in Sacramento, cockpit of decision-making for the planet’s seventh-largest economy, politics seems a remote concern compared to life, liberty and the weather. The ups and downs of political ambition do not fill the ether the way speculation rises like steam on the sidewalks of Albany, Boston, Harrisburg, Annapolis and certainly Concord, New Hampshire.

California is too big to be exotic, but New Hampshire, a theme park of nostalgia, is an inviting target for parachute journalism. Tom Stoppard defined a foreign correspondent in “Night and Day,” his 1978 play: “He’s someone who flies around from hotel to hotel and thinks the most interesting thing about any story is the fact that he has arrived to cover it.” If life imitates art, truth can mimic satire. Stoppard’s vision evoked the New Hampshire that flickered onto C-SPAN screens in January.

Like most Americans, I witnessed the Granite State’s show on television. I was in California, which had moved its primary from June to March. It was the first quadrennial cotillion I had missed reporting since 1968, the winter I spent trying to decipher the prose of George W. Romney and to duck the whimsical barbs of Eugene J. McCarthy. I did not miss joining those scratching for stories profound enough to justify our august presence, or at least our expense accounts.

The New Hampshire primary has been on the endangered species list since 1952, when voting citizens became more important than dealmakers in smoke-filled rooms. It’s too small, it’s too unrepresentative, the voters are monochromatic (98 percent white), but demographics will not dislodge the Granite State, nor will the wretched excess of the quadrennial media invasion. The state’s collective judgment might.

New Hampshire stamped passports to glory for Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard M. Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and George Bush. But its momentum, the “bounce,” faltered for Gary Hart, Michael Dukakis, Paul Tsongas, Pat Buchanan, and most notoriously for John McCain. His “Straight Talk Express” cannily converted the town meeting idea into a traveling “Truman Show,” a tableau of nonstop candor with the media in co-starring roles. Just days after his victory in New Hampshire, when McCain arrived at the Republican state convention in Burlingame, he fairly floated on magazine-cover euphoria.

One of the first questioners, Randy Shandobil of KTVU in Oakland, asked him about “a private fundraiser that might be perceived as hypocritical.” What about it? “I’m shocked, I’m shocked,” McCain said in a Claude Rains-in-Casablanca cadence that would have brought knowing chuckles among the scribes rolling along the off-ramps of Route 93 in New Hampshire.

The joke did not fly in Burlingame. Other reporters persisted and McCain said to Shandobil, “I don’t know anything about it, sir. I’ve been working 16, 18, 20 hours a day. I can’t give you an explanation. I’d be glad to refer you to my staff.” The paladin of “reform” sounded like another testy politician. Mike Murphy, McCain’s media adviser, fretted that reporters were steering his man into the quagmire of 20 statewide ballot issues, including gay marriage. He complained that “It’s not that the answers aren’t straight. The questions are crooked.”

When California abandoned its June primary to enhance its clout on the campaign calendar, the usual civic worriers began to keen and wail. The allegedly intimate cracker-barrel charm of New Hampshire would surrender to the frantic freeway distractions of California, alas. Personal politics would yield to television commercials. Money would dominate.

Not to worry. Candidates did not enrich California television stations because they had already blown their bankrolls elsewhere. George W. Bush showed a singular talent for adhering to Parkinson’s Second Law: Expenditure always rises to meet income. McCain squandered a more precious currency, his message. From the cozy cocoon of his bus, McCain dominated the media landscape of New Hampshire. A 19-point win in New Hampshire became a 24-point loss in California. His decline was similar in the other states that massed together for the first national primary.

The bad news for the Arizona senator was shared not only by New Hampshire but by the cause he espoused, the “reform” of campaign finance. McCain shook hands with Bill Bradley and signed a joint pledge in Claremont, New Hampshire. But the issue bored or angered the millions of voters who voted against it and them.

Neither candidate heard much about campaign finance from reporters, but the issue was a foremost concern of editorial writers. On “Face the Nation” the Sunday before Titanic Tuesday, Gloria Borger of CBS and U.S. News & World Report asked Bush: “Governor, why is it that every major New York newspaper today seems to have endorsed John McCain’s candidacy?” He replied, “I don’t know. You better ask the editors up there. He can have the editorial page endorsements. I want the votes of the people who are going to decide who the Republican nominee is. I think I’ve got a good chance in New York.”

So he did, and in California and Ohio, too. The message of “reform” from New Hampshire was confined to New England on March 7. The message, as amplified by the 700 or 800 reporters there did not, as a media cliché of campaigns past would have it, “resonate” in the precincts west of the Presidential Range of the White Mountains.

“In 1956, there had been just seven of us reporters in the final weekend, footsloggers all,” Theodore H. White recalled in his memoirs. “The old seven-man expeditionary press corps had consisted of an AP man; a UP man; a Boston Globe man; reporters of the Concord and Manchester papers, locals; a single magazine reporter, myself; and on the final weekend, The New York Times had sent its Boston Bureau Chief to Manchester to grace the event with the full majesty of the nation’s leading newspaper.”

Teddy White knew his numbers. He knew, too, that ballooning the size of the media mob seldom adds to the substance of human wisdom.

Martin F. Nolan writes for The Boston Globe from California.