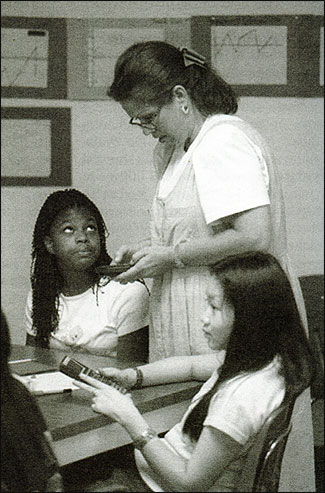

Photo by Michelle Patterson, The Lexington Herald-Leader.

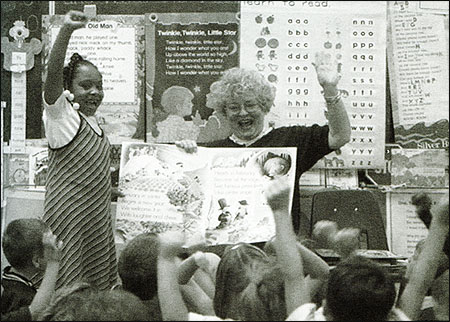

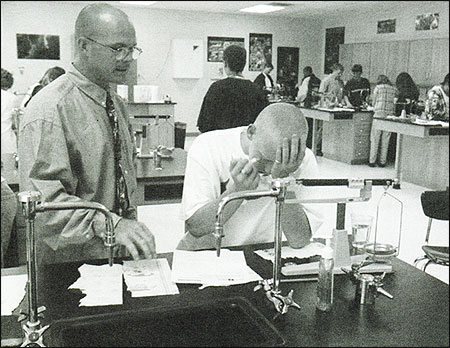

Education writers often try to measure the success of their local schools by analyzing such things as test scores, class sizes and poverty rates. But many reporters overlook one of the most influential factors in children’s school success: the quality of teachers.

A primary reason why education journalists tend to omit this measure from their reporting is the difficulties they confront in finding reliable data about teacher qualifications.

But as we at The Lexington (Ky.) Herald-Leader found, it can be done. The Lexington Herald-Leader published a four-part series last November that demonstrated how our state’s nationally acclaimed Kentucky Education Reform Act requires schools to set high expectation for students, but the same can’t be said for teachers.

In 1989, the state Supreme Court ruled the state’s public school funding mechanism unconstitutional. It ordered the General Assembly to start from scratch in redesigning more equitable funding. The result was the passage of the 1990 reform law, which has as its premise the belief that all students can learn at high levels. While the law was far from perfect, it did succeed in focusing Kentucky’s attention on school equity and student achievement.

But the law has failed to address teacher quality. There are two major reasons:

- Kentucky’s teachers union has used its political clout to successfully hold off attempts to toughen teaching standards.

- Lawmakers and bureaucrats have not had access to reliable data about the teacher workforce from which to make sound policy decisions.

These circumstances prompted us to want to look more closely at the issues involved with teacher competency and quality in our state. This meant also looking at the ways in which teachers are trained and whether their roles as teachers are adequately matched with their preparation.

In reporting this series, “The Learning Gap: High Expectations for Students, Low Standards for Teachers,” education reporters Holly E. Stepp, Linda B. Blackford and I documented that Kentucky’s teachers are able to receive a passing grade on their certification exams despite producing some of the lowest scores among similar test-takers throughout the South.

One invaluable resource we used for developing our reporting on this series was an electronic database of information about teachers that helped us to gauge their quality. We supplemented this analysis of data with interviews with policymakers, school administrators and teachers.

Arranging the interviews was easy; getting access to the necessary data was not. State education officials balked at turning over what they considered confidential information, including details about teachers’ academic records and their scores on state-mandated certification exams. And some data that we would like to have had, such as tests taken by teachers before the state began using PRAXIS and solid demographic data such as race and gender, simply didn’t exist in an electronic form that could be trusted.

The newspaper argued in a series of letters and telephone calls with the attorney for the Kentucky Department of Education’s Professional Standards Board that the information, as a whole, should not be regarded as confidential. Because Kentucky’s school reform law evaluates schools largely based on students’ test scores, why shouldn’t teachers be judged by their scores on teacher certification tests? Kentucky children are tested annually on what the state has decided they should know. Each year, as the reform law spells out, the bar for schools is raised slightly higher. If a school declines beyond a certain point, it faces sanctions.

But for Kentucky’s teachers, the standards haven’t changed.

Getting the information we thought we needed to do our own analysis of teacher preparedness and performance required two months of negotiation with the Standards Board’s attorney. In the end, state officials released the scores on the three core PRAXIS certification tests required in Kentucky and more than two dozen specialty tests used for individual teachers. They also released to us data about the college each teacher attended, deleting names or demographic information that might have allowed us to identify any individual. In a second database, the state released the PRAXIS test scores and told us the school district—but not the specific school—where each teacher went to work after becoming certified. The state’s data expert also changed the identifier for each person in the separate tables to make it impossible for us to match the tables and identify individuals.

For the most part, this arrangement worked. Only in some extreme examples—such as one teacher who took the three required certification tests a total of 22 times—was it easy to learn where that person ended up working. (That person never was able to pass all three tests and is a teacher working with “emergency certification” in a county in the south central part of the state, not far from where he or she graduated from college.)

We asked for data that went back 10 years. But we soon discovered that the state has very little electronic data about teachers prior to 1994. For us to have received hard copies of these records, after the state blacked out the names and other identifiable information, would not have been worth the cost or time it would have taken us to put it into the electronic form we needed to do our analysis. But we never faced that hurdle since the state couldn’t guarantee that the older data we wanted existed in any form.

Because there is so little electronic data about teachers hired before 1994, it became impossible for us to draw any solid conclusions about their qualifications as teachers. And this was illuminating because it meant state officials couldn’t do that kind of analysis, either. This is a significant problem since more than half of our state’s teachers have been in the classroom for at least 15 years. This means they never took the PRAXIS tests, which the state began using during the 1990’s, yet they still hold their lifetime certification. These teachers will remain certified despite never having taken any kind of test or doing anything more than attend to the annual required professional development, which we found to be mediocre in many places.

Now, having said that, all Kentucky teachers must get master’s degrees, but they have 10 years in which to do that. Many experts with whom we spoke for this story questioned the value of earning a degree that can be stretched over that length of time. Essentially, what our search for information let us know is that the older age of many of Kentucky’s teachers is a potential barrier if one is trying to find ways to gauge their qualifications.

Do these circumstances mean that many of Kentucky’s teachers aren’t qualified for their jobs?

The answer is that no one really knows, because nobody had ever tried before to compile the data and analyze it. Looking at the individual test scores by using Visual FoxPro, a computer program that lets us query information from a database, we were able to provide a glimpse at some of the information that is useful when measuring teachers’ competency:

- We could let readers know how many teachers passed certification tests the first time by combining the scores we had with other published data on passing scores.

- We could let readers know how many teachers failed the first time and in which colleges they were trained. (Such comparisons had not been made public before our series appeared.)

We found that in Kentucky, to no one’s surprise, people tend to go to college near where they were raised, and then they often return to their hometowns to teach. This means that students who came out of weak school systems tend to return to them. And this sets into motion a destructive cycle that makes academic excellence harder to achieve in these areas of the state.

By also analyzing the test scores, using a technique developed by an economics professor at Carnegie Mellon University, we learned how little is actually necessary to pass Kentucky’s teacher certification test. In fact, teachers were being allowed to pass the three basic tests and 18 specialty exams we reviewed by answering anywhere from 35 percent to half of the questions correctly.

The state agency that oversees teacher training told our reporters that it intends to raise the bar for passing teacher certification tests and expects to release specifics of its plan early this year. Officials say they will require new Kentucky teachers taking the PRAXIS tests to score at least as high as those elsewhere in the South, a region of the country in which these test scores, in general, are lower than in other areas.

So the state is faced with several dilemmas. Is it enough to want its teachers simply to score as well as they do elsewhere in the South? Or should the bar be set higher for them, as it is for its students? This remains a delicate balancing act for state officials, as our reporters discovered: raise the bar too high, too quickly, and not enough teachers will pass. That leaves students without teachers.

What we hope our series helped readers and policymakers understand is why quality matters in terms of how teachers do their jobs and how being lax in terms of letting teachers pass tests at lower thresholds might jeopardize children’s learning. Certainly our series did succeed in getting the state’s bureaucrats and policymakers to talk seriously about the need for better teacher training and higher qualifications. The day after our series began appearing in the newspaper, Kentucky’s Education Commissioner released the outline of a plan to improve education. Teacher training and quality were focal points of many of his initiatives. Since these had not been top agenda items before, the education establishment was caught by surprise.

And then in the middle of January, the newspaper learned the Governor was planning to create an 18-member task force to examine teacher training issues. One state lawmaker said teacher training has been a “hot topic” for some time, but that the paper’s series heightened awareness of the low standards set for teachers even more.

That, to some degree, was our mission in setting out to do this series. We wanted to take an aspect of education to which enough attention had not been paid, shine a light on what could be learned by carefully analyzing data, and provide some vivid examples—through our reporting—that would exemplify the harm that can occur if the problem is left untreated. It took a lot for us to get the numbers we needed out of the state bureaucracy, but our efforts to do so paid off handsomely when the articles ran and, for the first time, people were able to make connections where none had been visible before.

Photo by Michelle Patterson, The Lexington Herald-Leader.

Photo by Michelle Patterson, The Lexington Herald-Leader.

Linda J. Johnson is education writer for The Lexington Herald-Leader. Earlier this year she became the paper’s Computer-Assisted Reporting Coordinator. She began her involvement with computer-assisted reporting when she was health/environment reporter for The Vindicator, a paper in Youngstown, Ohio.