Journalism staggered away from the California recall election facing a witches’ brew of problems. Now journalists face the challenge of having an awful lot to learn about what happened, with perhaps not much time to learn what they need to know.

This challenge arises not because the coverage of the recall was bad. It wasn’t. In fact, by measures that serious journalists use to evaluate political coverage, it was very good. But good coverage didn’t seem to matter much and, in fact, it served to link journalists to an established political order that voters were determined to chase out of office three years ahead of schedule. This linkage seems apt since by philosophy and in practice, journalists are entwined in established politics. The recall election showed this graphically and also demonstrated how angry a significant segment of voters are at that established political order.

Warnings to Political Journalists

The warning I take away from the recall election’s coverage is that serious journalism risks becoming irrelevant to a political process that may be undergoing fundamental change. For those of us who want to see journalism be a major force in democratic society and not just a constitutionally protected license to make money, significant challenges lie ahead. The toughest one: figuring out how to reach growing numbers of disillusioned citizens without pandering to them or jettisoning our core values.

One area where some very hard thinking is necessary is the degree to which established journalism really savors and relies on the established political process, when much of the public is sick of it. Let others complain about the length of political campaigns, especially presidential ones. Journalists like long campaigns. In long campaigns, political journalists participate in the vetting. In a foreshortened campaign like the recall, name recognition and celebrity matter more, and the press matters less, much to the irritation of journalists.

The California reporters and editors I talked with disdained the recall process itself, not to mention this particular election. In print and in conversation, the chances of the recall getting on the ballot were minimized. This gave an early hint that reporters might not be on top of a story that was happening outside traditional political bounds. Then, once the recall was a reality, serious journalistic outlets committed themselves to serious coverage of the campaign and election.

That news coverage didn’t seem to make much difference. According to exit polls, two-thirds of the voters made up their minds more than a month before the election, or about the time of the first debate, in which Arnold Schwarzenegger did not participate. Fifty-five percent of these early deciders voted to recall Governor Gray Davis, and 47 percent voted for Schwarzenegger. For them, all those news stories, all those profiles, all those issue charts, and all those live TV stand-ups evidently made no difference.

Major newspapers—the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, The Sacramento Bee, and San Jose Mercury News—recommended in editorials a “no” vote on the recall and recommended no candidate to replace him. (Under California’s recall law, the recall question was a two-parter: First, yes or no on whether Davis should be recalled and second, which of the 135 candidates on the ballot—and not in alphabetical order!—should replace Davis if he were recalled.) This was a logically correct strategy, based on the conviction that the recall was a Bad Thing. But the election outcome shows that a huge segment of the population—more than the number who voted for Davis in 2002—did not share these editors’ disdain for the recall process.

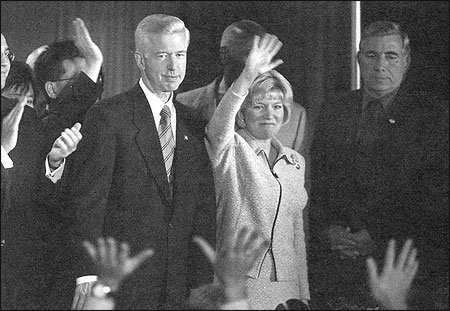

Governor Gray Davis loses recall election. Photo by J. Emilio Flores/La Opinión.

Reporting on a Celebrity Turned Candidate

Journalists worked hard to scrutinize Schwarzenegger. But he and his crew succeeded in appearing to be scrutinized without revealing anything significant. In fact, they successfully turned most of the scrutiny on its head. Schwarzenegger appeared on entertainment TV and radio shows such as “The Oprah Winfrey Show” and “Howard Stern” and “Larry King Live,” while avoiding more informed questioners of the political press and traditional avenues such as meetings with newspaper editorial boards. As his campaign chief said in August, two months before the election in early October, “This is not a position election. It’s a character election.” Schwarzenegger proceeded to ridicule attempts to probe his character and preemptively he warned that Governor Davis would try to drag the campaign to the gutter. He then coarsened his message with references to “puke politics” (his aides handed out barf bags and plastic vomit puddles to reporters) and vows to “kick some serious butt.”

These contradictions were dutifully reported. And it didn’t seem to matter.

Schwarzenegger’s name identification and celebrity trumped the tools that journalists had at their disposal. Schwarzenegger supporters had seen enough to make up their minds early, and no amount of standard journalistic effort to shame him into fuller disclosure, either about his character or his positions on issues, had any impact.

Many of these voters held a deep and seething anger that mainstream journalists have a hard time tapping into or even recognizing. Michael Lewis, writing in the New York Times Magazine, recounted chatting with Los Angeles talk-radio hosts John Kobylt and Ken Chiampou about their top-rated program in which they dialed in the political anger voters were feeling. “‘The challenge is to hold onto the tone,’ John says. Asked to describe the tone, Ken says, ‘Rabid dogs.’ John says: ‘I don’t know that part of the brain that shouts all these things you aren’t supposed to say in polite company, but that’s the part of the brain that we speak to.’ Ken: ‘People relate to the shouts. What differentiates us from a crazy man is that a lot of people agree with the shouts.’”

Whatever else the tone of 21st century mainstream journalism is, rabid dogs and shouting aren’t part of it. It’s so alien to most journalists that they have a hard time fathoming it as legitimate, let alone plumbing its depths and writing about it with power. And when we—here I lump myself in with serious journalists—enmesh ourselves, as political reporters, into the established political process, we become obvious targets of this same anger. While we might see ourselves as outsiders and watchdogs, keeping politicians honest and providing unbiased information to readers and viewers, the Kobylt-Chiampou audience regards us as part of an unholy cabal.

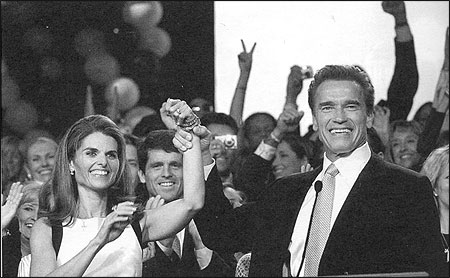

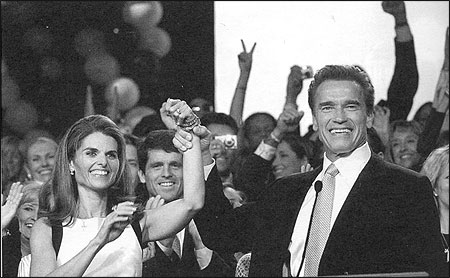

The newly elected governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and his wife, Maria Shriver, during his victory party in Los Angeles. Photo by Aurelia Ventura/La Opinión.

Watching the Anger Grow

Five days after the election, I wrote an analysis in the San Jose Mercury News about some of these issues, making the same point: that the established media are seriously disconnected from these citizens. The vitriolic reaction I got convinced me that I was right and also that my analysis of all of this had hardly calmed the seas. One person wrote representatively, “You seem to be saying, in a nutshell: There is a disconnect between journalists and the public. This is bad for society. So voters better shape up and get with the program.” From another reader: “I want to thank Jim Bettinger for explaining to me why I voted ‘yes’ on the recall and for Schwarzenegger as governor. I believed I was doing the right thing, but it turns out I was just plain too stupid to understand what the Los Angeles Times, the Mercury News, and other ‘Progressive’ newspapers were trying to tell me.”

Near the end of the campaign came the Los Angeles Times’s investigation into six women’s allegations that Schwarzenegger had groped them. When given a chance to respond to the women before the story was published, the Schwarzenegger campaign ignored the specifics and instead portrayed the women’s accounts as a tool of the Davis campaign. (After all, earlier they had successfully laid the foundation for this kind of a response.)

The campaign took on the newspaper, challenging its decision to publish the story five days before the election. After a loose and unspecific apology from Schwarzenegger on the day the story ran, the Schwarzenegger campaign made scourging the Times its message of the day. Maria Shriver, the candidate’s wife and a TV reporter herself, called the detailed and exhaustive story “gutter journalism.”

It was a tactic aimed at people prepared to believe the worst about the news media. And it seemed to work. Despite the swinish details, Schwarzenegger supporters whom I heard calling talk-radio programs took every opportunity to explain away the allegations. Others congratulated him for his apology, saying it made them more certain of their vote for him. For some, the very fact of publication seemed to prove to them that their candidate was an upright man who threatened the establishment; the problem wasn’t Arnold, it was the press.

The Impact of This Anger

Some intriguing consequences have emerged in the aftermath of the recall. One is that a lot of people got very turned on by the campaign. A survey by the Public Policy Institute of California found that people were paying attention to the recall in numbers and intensity similar to the September 11th terrorist attacks. About half of them said they were more interested in politics as a result and nearly half said they were more enthusiastic about voting. Indeed, about 1.675 million people more turned out to vote in the recall election than had voted in the regular election less than 12 months earlier. Noting this, at least eight California television stations are considering reopening their state capital bureaus. Journalists in other sections of the country might find this amazing, but not since 1988 has a local television station had a Sacramento bureau.

My own thinking about the recall has shifted since the election. I’ve gone from being opposed on principle to a more ambivalent view. All the reasons to have opposed the recall are still there. But, I ask myself, if that many people are that upset about the way the state is being run, is it good government to deny them a political voice for that anger for three more years?

Serious journalists should have similar ambivalence about what happened and what they’re going to do about it. Yes, Schwarzenegger’s image ran roughshod over nuanced and critical coverage in this election. Yes, this was the clichéd “perfect storm” of an unpopular governor, an international icon, and a short campaign. And yes, rabid dogs and shouting are exactly not what many of us got into journalism to cover.

But the fact remains that a significant segment of the public believes— to a moral certainty—that mainstream media work from an agenda of actively promoting liberal political goals and that they work in tandem with the traditional political system. As journalists, we need to figure out ways to connect with these angry voters and disentangle ourselves from the political establishment, rather than dismiss this new political force as crazies who just aren’t like us.

Jim Bettinger is director of Stanford University’s John S. Knight Fellowships for Professional Journalists and a former newspaper editor.

This challenge arises not because the coverage of the recall was bad. It wasn’t. In fact, by measures that serious journalists use to evaluate political coverage, it was very good. But good coverage didn’t seem to matter much and, in fact, it served to link journalists to an established political order that voters were determined to chase out of office three years ahead of schedule. This linkage seems apt since by philosophy and in practice, journalists are entwined in established politics. The recall election showed this graphically and also demonstrated how angry a significant segment of voters are at that established political order.

Warnings to Political Journalists

The warning I take away from the recall election’s coverage is that serious journalism risks becoming irrelevant to a political process that may be undergoing fundamental change. For those of us who want to see journalism be a major force in democratic society and not just a constitutionally protected license to make money, significant challenges lie ahead. The toughest one: figuring out how to reach growing numbers of disillusioned citizens without pandering to them or jettisoning our core values.

One area where some very hard thinking is necessary is the degree to which established journalism really savors and relies on the established political process, when much of the public is sick of it. Let others complain about the length of political campaigns, especially presidential ones. Journalists like long campaigns. In long campaigns, political journalists participate in the vetting. In a foreshortened campaign like the recall, name recognition and celebrity matter more, and the press matters less, much to the irritation of journalists.

The California reporters and editors I talked with disdained the recall process itself, not to mention this particular election. In print and in conversation, the chances of the recall getting on the ballot were minimized. This gave an early hint that reporters might not be on top of a story that was happening outside traditional political bounds. Then, once the recall was a reality, serious journalistic outlets committed themselves to serious coverage of the campaign and election.

That news coverage didn’t seem to make much difference. According to exit polls, two-thirds of the voters made up their minds more than a month before the election, or about the time of the first debate, in which Arnold Schwarzenegger did not participate. Fifty-five percent of these early deciders voted to recall Governor Gray Davis, and 47 percent voted for Schwarzenegger. For them, all those news stories, all those profiles, all those issue charts, and all those live TV stand-ups evidently made no difference.

Major newspapers—the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, The Sacramento Bee, and San Jose Mercury News—recommended in editorials a “no” vote on the recall and recommended no candidate to replace him. (Under California’s recall law, the recall question was a two-parter: First, yes or no on whether Davis should be recalled and second, which of the 135 candidates on the ballot—and not in alphabetical order!—should replace Davis if he were recalled.) This was a logically correct strategy, based on the conviction that the recall was a Bad Thing. But the election outcome shows that a huge segment of the population—more than the number who voted for Davis in 2002—did not share these editors’ disdain for the recall process.

Governor Gray Davis loses recall election. Photo by J. Emilio Flores/La Opinión.

Reporting on a Celebrity Turned Candidate

Journalists worked hard to scrutinize Schwarzenegger. But he and his crew succeeded in appearing to be scrutinized without revealing anything significant. In fact, they successfully turned most of the scrutiny on its head. Schwarzenegger appeared on entertainment TV and radio shows such as “The Oprah Winfrey Show” and “Howard Stern” and “Larry King Live,” while avoiding more informed questioners of the political press and traditional avenues such as meetings with newspaper editorial boards. As his campaign chief said in August, two months before the election in early October, “This is not a position election. It’s a character election.” Schwarzenegger proceeded to ridicule attempts to probe his character and preemptively he warned that Governor Davis would try to drag the campaign to the gutter. He then coarsened his message with references to “puke politics” (his aides handed out barf bags and plastic vomit puddles to reporters) and vows to “kick some serious butt.”

These contradictions were dutifully reported. And it didn’t seem to matter.

Schwarzenegger’s name identification and celebrity trumped the tools that journalists had at their disposal. Schwarzenegger supporters had seen enough to make up their minds early, and no amount of standard journalistic effort to shame him into fuller disclosure, either about his character or his positions on issues, had any impact.

Many of these voters held a deep and seething anger that mainstream journalists have a hard time tapping into or even recognizing. Michael Lewis, writing in the New York Times Magazine, recounted chatting with Los Angeles talk-radio hosts John Kobylt and Ken Chiampou about their top-rated program in which they dialed in the political anger voters were feeling. “‘The challenge is to hold onto the tone,’ John says. Asked to describe the tone, Ken says, ‘Rabid dogs.’ John says: ‘I don’t know that part of the brain that shouts all these things you aren’t supposed to say in polite company, but that’s the part of the brain that we speak to.’ Ken: ‘People relate to the shouts. What differentiates us from a crazy man is that a lot of people agree with the shouts.’”

Whatever else the tone of 21st century mainstream journalism is, rabid dogs and shouting aren’t part of it. It’s so alien to most journalists that they have a hard time fathoming it as legitimate, let alone plumbing its depths and writing about it with power. And when we—here I lump myself in with serious journalists—enmesh ourselves, as political reporters, into the established political process, we become obvious targets of this same anger. While we might see ourselves as outsiders and watchdogs, keeping politicians honest and providing unbiased information to readers and viewers, the Kobylt-Chiampou audience regards us as part of an unholy cabal.

The newly elected governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and his wife, Maria Shriver, during his victory party in Los Angeles. Photo by Aurelia Ventura/La Opinión.

Watching the Anger Grow

Five days after the election, I wrote an analysis in the San Jose Mercury News about some of these issues, making the same point: that the established media are seriously disconnected from these citizens. The vitriolic reaction I got convinced me that I was right and also that my analysis of all of this had hardly calmed the seas. One person wrote representatively, “You seem to be saying, in a nutshell: There is a disconnect between journalists and the public. This is bad for society. So voters better shape up and get with the program.” From another reader: “I want to thank Jim Bettinger for explaining to me why I voted ‘yes’ on the recall and for Schwarzenegger as governor. I believed I was doing the right thing, but it turns out I was just plain too stupid to understand what the Los Angeles Times, the Mercury News, and other ‘Progressive’ newspapers were trying to tell me.”

Near the end of the campaign came the Los Angeles Times’s investigation into six women’s allegations that Schwarzenegger had groped them. When given a chance to respond to the women before the story was published, the Schwarzenegger campaign ignored the specifics and instead portrayed the women’s accounts as a tool of the Davis campaign. (After all, earlier they had successfully laid the foundation for this kind of a response.)

The campaign took on the newspaper, challenging its decision to publish the story five days before the election. After a loose and unspecific apology from Schwarzenegger on the day the story ran, the Schwarzenegger campaign made scourging the Times its message of the day. Maria Shriver, the candidate’s wife and a TV reporter herself, called the detailed and exhaustive story “gutter journalism.”

It was a tactic aimed at people prepared to believe the worst about the news media. And it seemed to work. Despite the swinish details, Schwarzenegger supporters whom I heard calling talk-radio programs took every opportunity to explain away the allegations. Others congratulated him for his apology, saying it made them more certain of their vote for him. For some, the very fact of publication seemed to prove to them that their candidate was an upright man who threatened the establishment; the problem wasn’t Arnold, it was the press.

The Impact of This Anger

Some intriguing consequences have emerged in the aftermath of the recall. One is that a lot of people got very turned on by the campaign. A survey by the Public Policy Institute of California found that people were paying attention to the recall in numbers and intensity similar to the September 11th terrorist attacks. About half of them said they were more interested in politics as a result and nearly half said they were more enthusiastic about voting. Indeed, about 1.675 million people more turned out to vote in the recall election than had voted in the regular election less than 12 months earlier. Noting this, at least eight California television stations are considering reopening their state capital bureaus. Journalists in other sections of the country might find this amazing, but not since 1988 has a local television station had a Sacramento bureau.

My own thinking about the recall has shifted since the election. I’ve gone from being opposed on principle to a more ambivalent view. All the reasons to have opposed the recall are still there. But, I ask myself, if that many people are that upset about the way the state is being run, is it good government to deny them a political voice for that anger for three more years?

Serious journalists should have similar ambivalence about what happened and what they’re going to do about it. Yes, Schwarzenegger’s image ran roughshod over nuanced and critical coverage in this election. Yes, this was the clichéd “perfect storm” of an unpopular governor, an international icon, and a short campaign. And yes, rabid dogs and shouting are exactly not what many of us got into journalism to cover.

But the fact remains that a significant segment of the public believes— to a moral certainty—that mainstream media work from an agenda of actively promoting liberal political goals and that they work in tandem with the traditional political system. As journalists, we need to figure out ways to connect with these angry voters and disentangle ourselves from the political establishment, rather than dismiss this new political force as crazies who just aren’t like us.

Jim Bettinger is director of Stanford University’s John S. Knight Fellowships for Professional Journalists and a former newspaper editor.