As technology assumes an ever-increasing presence in our lives, deep reporting on technology and nuanced critiques of technology become more important, too. This excerpt from "Toward a Constructive Technology Criticism" by Sara M. Watson, a research fellow at Columbia Journalism School's Tow Center for Digital Journalism, is a critique of technology criticism and recommendations for improving it. For an examination of the current state of technology reporting, see "Access, Accountability Reporting and Silicon Valley" by Adrienne LaFrance in Nieman Reports. Read the complete Tow Center report, style guide for technology writing, and annotated syllabus here.

Despite the possibilities for a critical stance that transcends the progress/anti-progress duality, why do negative associations still drown out the potential for more considered and skeptical forms of criticism when it comes to technology? In part, this is because the criticism that major media outlets elevate is so often riddled with problematic styles, tactics, assumptions, and ideologies. Matt Buchanan laments: “It sucks that the word ‘criticism’ has been ruined.” And there are a number of ways mainstream criticism and Critics have failed us so far.

Traps of Styles and Tactics

Most Critics perpetuate negative associations by using unexamined assumptions and ideologies. In this section, I list common fallacies and follies present in much contemporary, mainstream technology criticism. In doing so, I aim to both surface hidden patterns in the writing of current technology criticism and to empower future technology critics to avoid these traps. Further examples of common framing problems and clichés found in technology writing are provided in the style guide in Appendix B.

| Style and Tactic Traps | Questions to Ask of the Critics |

|---|---|

| Controversy and Counter-Narrative | Is this a real concern, or is the easy takedown of a trendy topic? |

| Missing People | What do actual users think, and how do they use the technology? |

| Generalizing Personal Gripes | Is this representative of a larger concern? |

| Cults of Personality, Bullying, and Misrepresentation | Does focusing on this one person make us miss the bigger picture? |

| Preaching to the Choir | What audience is this trying to convince? |

| Deconstruction Without Alternatives | If this is the problem, what can we do about it? |

Style and Tactic Trap: Controversy and Counter-Narrative

Ironically, mainstream technology criticism is itself a product of the internet and media conditions it seeks to criticize. Contrarian views are clickbait. They lead to totalizing headlines like “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” Critics have often fallen into the trap of the vacuum-filling, counter-narrative strategy to remind readers why they should all be worried.

Critical writing, particularly in the quick cycle of hot takes, has to garner attention. They rely on sensationalizing tactics, akin to those of cable news, as law professor and contributor to The New Yorker Tim Wu puts it in his review of Evgeny Morozov’s book. Morozov’s vindictive personal attacks and counter-narrative arguments grab attention, and he’s successful because such controversy and contrarian headlines result in clicks.

Henry Farrell dissects how contrarian and controversy tactics undermine critics’ messages, using Morozov as an example: “Morozov’s success shows how trolling can be a viable business model for aspiring public intellectuals . . . [Critics] work within the same system as their targets, in ways that compromise their rejoinders, and stunt the development of more useful lines of argument.” Morozov himself acknowledges this fact: “I’m very conscious of what I’m doing . . . I’m destroying the internet-centric world that has produced me. If I’m truly successful, I should become irrelevant.” While these strategies may draw attention to the problems that Critics raise, they end up doing more harm than good by clouding the argument and incensing their targets to the point of ignoring the message.

Style and Tactic Trap: Missing People

More than just missing the social and political factors that bring a technology into existence, Critics of technology often fail to address the people for whom the technology is made. In his review of Morozov’s To Save Everything, Alexis Madrigal points to the missing users: “Without a functioning account of how people actually use self-tracking technologies, it is difficult to know how well their behaviors match up with Morozov’s accounts of their supposed ideology.”

Critics also tend to write in the idiomatic royal “we” without representing real users’ interests or perspectives. Madrigal again articulates the importance of talking to people: “It is in using things that users discover and transform what those things are. Examining ideology is important. But so is understanding practice.” Criticisms that don’t take people into account—either users themselves or the social systems in which they live—are functionally useless to readers, policymakers, and the creators of these technologies.

Much mainstream criticism also fails to understand the development cycle within technology companies. Most tech writers have not spent time working within a technology company, and they usually don’t gain access to developers, engineers, and designers within the company without careful mediation through corporate PR. So while Critics might be capable of writing more nuanced critiques that take into account the human side of technological development and management, this would require a greater degree of access and mutual trust between tech companies, reporters, and critics. For example, greater understanding of software development would lend more credibility and efficacy to outsider critiques.

Style and Tactic Trap: Generalizing Personal Gripes

Another common mode in mainstream technology criticism is for the Critic to generalize personal gripes about technology into blanket judgments about technological progress. This is the mode used by Franzen when he complains about Twitter, a technology that threatens his livelihood by distracting him from his writing practice and changing the way his readers consume media. It can also be seen in Morozov’s description of the safe in which he locks his internet router so he can write his damning screeds without distraction. Lanier has issued similar laments about the lost analog range in lossy, compressed music. And Carr has expressed his own wistful longing for the stick shift with which he learned to drive.

In this mode of mainstream criticism, Critics seem to worry about the collective present and future on our behalf, but they are actually worried about themselves. Morozov recognizes this, and so he has headed back to the academy to add further credibility to his gripes: “It is easy to be seen as either a genius or a crank. If you have a Ph.D., at least you somewhat lower the chances that you will be seen as a crank.” But even a Ph.D. can’t generalize the personal gripes that some Critics project onto the broader culture. Picture the Critic, sitting in his leather office chair, stroking his chin and milling over his analysis of society without evidence beyond his subjective experience. This is an association a number of my interviewees cited as a deterrent to being known as a Critic.

Style and Tactic Trap: Cults of Personality, Bullying, and Misrepresenting Ideas

Though it is important to understand the ideological positions of the titans of the tech industry, some technology Critics unduly focus attention on individual personalities in isolation from their contexts. Profiles and takedowns of Silicon Valley moguls like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Mark Zuckerberg, and Tim O’Reilly make for compelling (anti-)hero narratives, but they often miss the details of the larger system and the labor that surrounds them. These profiles also perpetuate the mystique of ownership and power attributed to these Silicon Valley leaders.

Morozov, in particular, is guilty of personal, vindictive, intellectual bullying of his targets, no matter what side of the argument they represent. Whether it’s commentators like Jeff Jarvis, Tim O’Reilly, and Clay Shirky, or the heads of technology companies, Morozov punches up, down, and sideways. One of Morozov’s mentors, Joshua Cohen, lifts the veil: “I don’t think he has written anything yet that withstands the kind of close critical scrutiny that he gives to other people’s work.” And despite his close attention, Morozov ends up “distorting their arguments (sometimes to the point of intimating that these people are saying the opposite of what they do say) . . . In ways that are both offensive and extravagantly wrong, Morozov tempts these intellectuals to respond in public.” And, Farrell argues, this continues the cycle of the clickbait attention economy.

Though a narrow focus on personalities can miss important context, this kind of criticism can also be an important corrective for the hero narrative so common in technology circles. For example, in writing for Valleywag, Sam Biddle and Nitasha Tiku took a tabloid approach to the industry, holding the industry to account for its hypocrisies, excess, and thinly veiled ideologies. Clearly critical, snarky, and often mean in the way many early Gawker network bloggers were, John Herrman and Elmo Keep both said they missed Biddle’s devotion to “slash in every direction.”

Style and Tactic Trap: Preaching to the Choir

Mainstream critical writing performs well because it appeals to readers’ established positions and biases. Incendiary posts target skeptical readers likely to forward on these pieces to their family members. As Tim Wu puts it, “Because of its hostile and abstract air, the main audience for Morozov’s work won’t be Silicon Valley readers, but tech-hating intellectuals warmed by his attacks because they already despise Google, Twitter, and maybe just the West Coast in general.” These arguments do little to change minds. They dig deeper into an entrenched position, and they fall on deaf ears, thus minimizing their potential for impact.

Style and Tactic Trap: Deconstruction Without Alternatives

One of the most widely recognized Critics of technology has made it his mission to destroy the industry and everyone associated with it. Writing against what he calls “solutionist” thinking, i.e. that all problems are potentially solvable (and often with technology), Morozov facilely avoids offering alternative solutions. “Morozov insists that his refusal to be useful is its own kind of usefulness---and even, as he recently wrote in one of his essays for German newspapers, an intellectual duty.” Senior editor at The Nation Sarah Leonard acknowledges that Morozov’s tactics have their place: “Some people are just born critics. They’re not going to come up with the answers. That’s fine. If their critiques are sharp and intellectually productive, that’s great.” Heffernan adds of Morozov, “He put so much heavy twentieth-century pressure on these seemingly fragile forms.”

Madrigal acknowledges, “It’s a lot to ask of a critic to both demolish the existing ideology of technology and replace it with something better, but Morozov has never had small ambitions.” Morozov’s critique of solutionism conveniently inoculates him from providing solutions or alternatives to the current state of technocratic thinking. Perhaps he offers different ways of thinking about technology and its capabilities for influencing and producing change, but these are little more than tools for thinking and certainly not tools for construction.

Traps of Ideology and Unexamined Positions

Though they are willing to deconstruct the logic and assumptions of their targets, Critics are sometimes opaque about their own biases, ideological positions, and disciplinary blind spots. This section attempts to lay out the traps of ideology and unexamined positions that underlie much contemporary criticism.

| Traps of Ideology and Unexamined Positions | Questions to Ask of the Critics |

|---|---|

| Technological Determinism and Progress | Does this technology coerce and limit users? Or are there alternative uses? |

| Fear Mongering, Sensationalism, and Moral Panics | How likely is this to happen? And haven’t we always worried about these concerns? |

| Dualisms and Zero-Sums | Does it have to be either or? Does this oversimplify the issue? |

| Defeatism of the Critical Stance | What is this criticism trying to accomplish? |

Ideology Trap: Technological Determinism and Progress

Is technological determinism making us stupid? Or just making us write bad headlines? Technological determinism is a common blind spot in much of contemporary criticism. While addressing important questions, much criticism falls toward a determinist stance, blaming technologies’ social impacts on the design or the device and leaving less room for more subtle investigations of use and adoption practices. The idea that technology has a teleology, that there is an inevitability to its development and effects, removes all human agency from the equation, both in the consumption and the production of technologies.

It is compelling to think that technology does things to us. Doing so acknowledges the power dynamics at play in sociotechnical systems. Technologies do embed coercive potential in their default designs, but determinist framings perpetuate the myth that technology is the driving force shaping behavior and diminish the importance of the “socio” in sociotechnical systems. While these framings pose simple questions that generate clicks, they do little to further readers’ understanding of the complexity of the interactions between humans and human-built systems. Morozov recognizes this problematic position: “The very edifice of contemporary technology criticism rests on the critic’s reluctance to acknowledge that every gadget or app is simply the end point of a much broader matrix of social, cultural, and economic relations.”

Ideology Trap: Fear Mongering, Sensationalism, and Moral Panics

The most sensational forms of criticism offer alarmist, fear-mongering warnings about a loss of humanity. Most of what Critics put forward in opposition to technological trends does little more than appeal to readers’ existing anxieties.

It can be hard for critics, who have to clarify what is at stake in their writing, to avoid overstating their concerns. In The Glass Cage, Carr chastises the “alarmist tone” of Critics warning of a near future where robots take our jobs, yet Carr himself does not hesitate to use the buzzwords of moral panic. He points to the ills of depression, suicide, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder that plague our age, and he ties them back to the effects of a frictionless, automated existence.

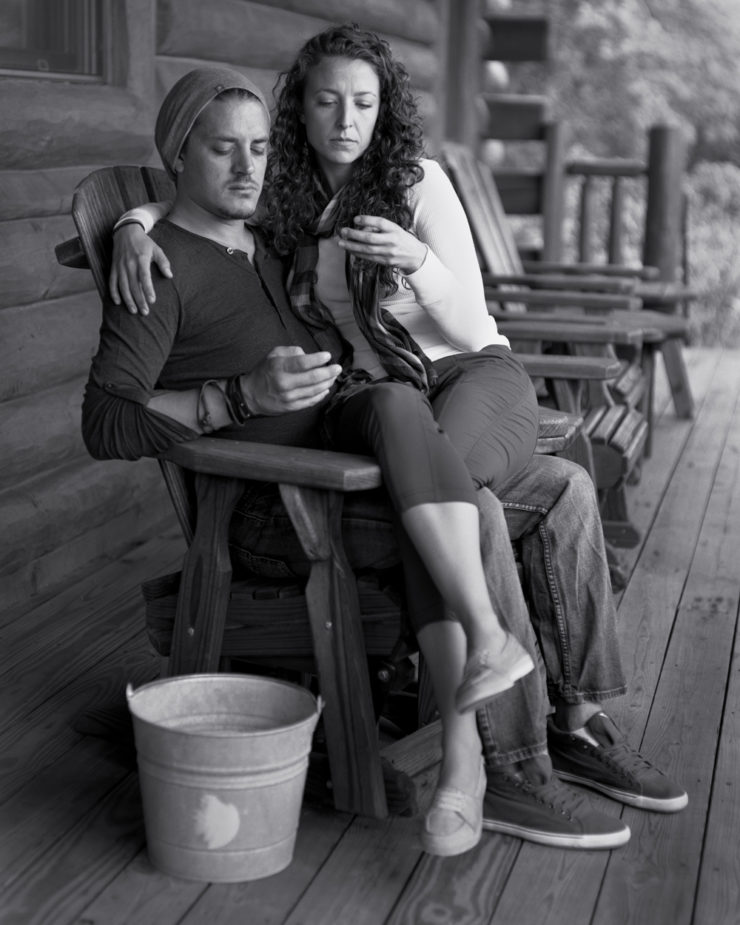

Similarly, Sherry Turkle worries for the sake of our children, about their ability to have conversations in the traditional face-to-face sense: “One teacher observed that the students ‘sit in the dining hall and look at their phones. When they share things together, what they are sharing is what is on their phones.’ Is this the new conversation? If so, it is not doing the work of the old conversation. The old conversation taught empathy. These students seem to understand each other less.”

Throughout history, commentators have worried about the effect of technologies on vulnerable populations, namely women and children. Genevieve Bell, an anthropologist at Intel, has identified factors that prime us for moral panics: technologies that change our relationship to time, space, and each other. Deputy editor of The Economist and author Tom Standage has collected numerous examples of technologies that evoked strong cultural concern upon their introduction, from the novel, to the railroad, to the photographic camera. Throughout history, dramatic change has evoked this response, manifesting as moral panic narratives and sensationalized worst-case scenarios.

Ideology Trap: Dualisms and Zero-Sums

Mainstream criticism of technology can also tend toward polarities, thereby mimicking the either/or binaries of the technologies they examine. Technology is either making people smarter or making people dumber (see Carr’s “Is Google Making Us Stupid?”). People are either technophobes or technophiles (Evgeny Morozov and Kevin Kelly, respectively, by Carr’s estimation), shilling utopian or dystopian visions for the future of the world. The most contrarian technology Critics lead readers to believe that we can’t have it both ways.

Many Critics are guilty of romanticizing the past or fetishizing the real. Carr exclaims: The screen is but a “shadow of the world.” “We’re disembodying ourselves, imposing sensory constraints on our existence. With the general purpose computer, we’ve managed, perversely enough, to devise a tool that steals from us the bodily joy of working with tools.” Turkle similarly poses a zero-sum-game between digital communication and face-to-face conversation. She has recently turned her attention toward the ways technology damages interpersonal relationships by removing the ability to communicate with each other, but her work skirts over the fact that communication technologies connect people who may not share physical space. Her work today privileges the real rather than exploring the possibilities of the virtual as she has done in the past. These Critics’ arguments end up favoring the status quo, which is why it is all too easy to dismiss their critiques as conservative and anti-progress. They romanticize the past, perpetuating a dualist binary between life before and after the selfie, or between the real and the virtual.

Dualist criticism also drives readers toward binary questions rather than critical thinking. This kind of criticism offers either utopian or dystopian narratives of the near future. Author and activist Astra Taylor aptly describes it in the introduction to The People’s Platform: “The argument about the impact of the internet is relentlessly binary, techno-optimists facing off against techno-skeptics.” She unpacks an example in an article with technology and art writer Joanne McNeil:

In the current framework, the question posed by TheNew Yorker panel, “Is Technology Good for Culture?” can be answered only with a yes or no---and plotted as it is along the binary logic of 1s and 0s, it chiefly serves to remind culture critics that the Silicon Valley mindset has already won. Though they appear to stand on opposite sides of the spectrum---unapologetic utopian squaring off against wistful pessimist---the Shirkys and Franzens of the world only reinforce this problem: things will get better or worse, pro or con.

As early as 1998, technology writers have been making the case for more nuanced rather than polarized writing about technology. A manifesto drafted by Andrew Shapiro, David Shenk, and Steven Johnson on Technorealism.org argued for moving beyond framing technological change as either good or bad. They warned: “Such polarized thinking leads to dashed hopes and unnecessary anxiety, and prevents us from understanding our own culture.”

Writing today, Virginia Heffernan resists the reductive binaries that publications so often employ in headlines. Technology is both good and bad, makes us smart and stupid, connects us and separates us. For Heffernan, the internet is Magic *AND* Loss. Her aesthetics of the internet leave room for both possibilities, often at the same time. Rather than directing us to a binary conclusion, she encourages us to explore the murky spaces in between.

Ideology Trap: Defeatism of the Critical Stance

In his defeatist salvo, Morozov never answers his own opening question, “What can technology criticism accomplish?” He laments, “Disconnected from actual political struggles and social criticism, technology criticism is just an elaborate but affirmative footnote to the status quo.” If popular discourse about technology and society is dominated by this small set of Critics currently standing for mainstream technology criticism, then Morozov’s concerns are founded: “Contemporary technology criticism in America is an empty, vain, and inevitably conservative undertaking. At best, we are just making careers; at worst, we are just useful idiots.”

There is a place for the radical, deconstructive type of criticism Morozov practices and calls for, and he can be credited for his prolific contributions where a dearth of skepticism in the discourse about technology once existed. But intellectual, politicized work naming the neoliberal technological determinism of Silicon Valley only offers language to describe the present state, and “doesn’t provoke a lot of further development,” suggests Sarah Leonard. Writers like Morozov and Carr end up leaving readers only with the sense that we should worry and think twice about adopting emerging technologies. This is not a practical or productive criticism of technology.

A Diverse Technology Discourse

My aim in outlining these traps of problematic styles, tactics, ideologies and unexamined positions is to illustrate how they influence our wider understanding of what technology criticism is, what it does, what its aims and audiences are, and how effective it is. If these tactics stand in for what technology criticism means to most people, how can writers reach the readers who aren’t willing to abandon their smartphones or the engineers whose livelihoods depend on the continued success of the industry?

Alexis Madrigal relates that there’s space for all tactics and approaches, that even the most problematic strategies contribute to the conversation and force the issues into the public consciousness. He advocates for a mixed-methods, intersectional approach to criticism that leaves room for all these approaches. Madrigal takes a more open stance to critical work that wants to produce change:

"[You] need people who are super radical, anti-technology, anti-capitalist. You also need people inside the companies who are just barely more ethical than the next person. Also you need people who try and connect the big ideas of technology companies with the ethical standards the country at least nominally sets out for itself. You need all those different things. You need people who are completely uninterested in the ideological battles that are super into reporting the dirt on these companies. Exactly how things are going. You need all of those different components, I think, and I would just say, in my more humble moments, that I realize I’m just one lever."

Still, as a result of these tactics, many journalists and bloggers are reluctant to associate their work with criticism or identify themselves as critics. And yet I find a larger circle of journalists, bloggers, academics, and critics contributing to the public discourse about technology and addressing important questions by applying a variety of critical lenses to their work. Some of the most novel critiques about technology and Silicon Valley are coming from women and underrepresented minorities, but their work is seldom recognized in traditional critical venues. As a result, readers may miss much of the critical discourse about technology if they focus only on the work of a few, outspoken intellectuals.

If technology criticism is to be useful, to accomplish something, then it has to acknowledge and include in it a suite of strategies, positions, approaches, and voices. Through my interviews and reading, I find that a wider circle of journalists, bloggers, and academics are contributing to a critical discourse about technology by contextualizing, historicizing, and giving readers tools for understanding our relationship to technologies in our everyday lives. And yet these writers are reluctant to be associated with “criticism” because of the negative connotations and destructive tactics described above.

Even if a wider set of contributions to the technology discourse is acknowledged, I find that technology criticism still lacks a clearly articulated, constructive agenda. Besides deconstructing, naming, and interpreting technological phenomena, criticism has the potential to assemble new insights and interpretations. In response to this finding, I lay out the elements of a constructive technology criticism that aims to bring stakeholders together in productive conversation rather than pitting them against each other. Constructive criticism poses alternative possibilities. It skews toward optimism, or at least toward an idea that future technological societies could be improved. Acknowledging the realities of society and culture, constructive criticism offers readers the tools and framings for thinking about their relationship to technology and their relationship to power. Beyond intellectual arguments, constructive criticism is embodied, practical, and accessible, and it offers frameworks for living with technology.

This research was funded by the Tow Center through a gift from The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. For more on this argument for a constructive technology criticism, read the complete Tow Center report, style guide for technology writing, and annotated syllabus here.