“See all the Chinese out there?” says the gift shop girl to her co-worker in the Shangri-La Hotel, “the security people have arrived!”

RELATED ARTICLE

"White House Redfines Tiananmen Square"

- Philip CunninghamIt’s been a while since the presence of Chinese in a Western-style hotel would be cause for comment, but then again, Beijing’s five-star Shangri-La is serving as the nerve center for the White House traveling press office, temporary home to the hundreds of journalists assigned to cover President Clinton in China. Plainclothes Chinese officers in the lobby lounge outnumber the jet-lagged visitors, most of whom will spend their time in Beijing in the air-conditioned comfort of this hotel. An important part of the job of public security men is to monitor and minimize contact between locals and foreigners, especially journalists.

Ruthless deadlines, commercial ratings and the desire not to be outdone by rivals certainly puts pressure on journalists these days. But it was disheartening to see some of America’s best-known journalists spend the entire day in the hotel, going from briefing room to dining room, picking up handouts and going back to their desks and filing their stories on June 27. No time to dig, no access to primary participants, no luxury to question official sources too deeply or look around the fringes for other views. Instead the print and television reporters unwittingly served as scribes and fashion cameramen for scripted summit photo opportunities and press conferences. Being abroad on unfamiliar turf in which the national aspirations and pride of two countries were put on the line had the effect of transforming normally skeptical American reporters into co-conspirators of American officialdom spreading the word as spun by the White House.

To get into the White House traveling press headquarters, one had to pass a Chinese security guard who checked for photo identification and then run the gauntlet past two somewhat more subtle American gatekeepers who greeted familiar faces with a smile and unfamiliar ones with a “may I help you?” Although not part of the officially credentialed press, I got inside the restricted area without the requisite laminated photo ID merely by walking straight in (that bold tactic worked only once).

It was like crossing the Pacific in a single leap, for all of a sudden I found myself back in America, where the press enjoys being spoon-fed.

The press hospitality room featured half a dozen dining tables covered in white tablecloths and a long buffet table offering self-serve hot entrees, desserts, coffee and tea. Even with the air-conditioning on full blast, it was warm there, so the two coolers stocked with mineral water and sweet bottled drinks got the most action.

The newsroom was a cavernous, windowless function room, with rows of chandeliers above and long banks of phones and jacks for laptop computers below. Desk space was tightly rationed, identified by name of publication. Near the entrance, a makeshift office complete with secretarial staff and high-speed copy machines churned out transcripts of speeches and news updates. A USIA information table offered news updates called “Afternoon Wire Stories.”

Other tables had information on where to buy “chinoiserie” and sign-ups for trips to the Great Wall and the Forbidden City for journalists not included in the pool but invited to follow the President’s sightseeing forays.

Televisions were dispersed throughout the hotel press center. Cramped venues where Clinton spoke, such as Chongwenmen Church and Beijing University Auditorium, necessitated strict pool coverage, which meant that the hotel ballroom was as close as some reporters got to the action.

Orville Schell, a China-watcher and Dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California at Berkeley, was among the anointed members of the press, White House press ID dangling from his neck, who watched the Clinton-Jiang press conference on television. Eyes glued to the screen, he told me Clinton’s comments about Tiananmen were an exciting development.

Given the popularity of Schell’s writings on China, his reaction would be watched closely by those new to the China field who were not sure of what they were seeing and hearing. Ditto for television people who often tuned to CNN to see what was “happening.” Put a hundred journalists in a room and certain ideas will become reinforced, amplified and adopted as fact simply because an opinion leader has said so.

There was a buzz of excitement as Clinton politely disagreed with Jiang Zemin on the significance of Tiananmen and the Dalai Lama. But nothing could compare to the gleeful boasts of the White House spin team who declared the televised press conference a resounding victory for the U.S.

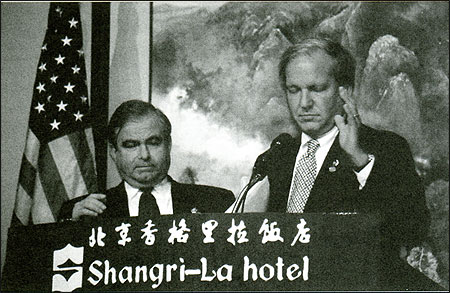

National Security Advisor Sandy Berger arrived at the press center shortly before four with Press Secretary Mike McCurry to summarize the day’s events. How convenient! First watch the press conference on TV, follow it with a “live” meeting with two top Clinton aides. The result? A ready-made story that could be zapped by modem back to the U.S. without even leaving the hotel.

Standing in front of a bank of TV cameras and rows of earnest journalists jotting notes, Berger gushed with child-like enthusiasm, saying the “historic press conference” provided a “powerful discussion beaming across China” that was the “first time for a leader to address Tiananmen so directly.”

Better-known correspondents like Sam Donaldson, Ann Compton and Wolf Blitzer got most of the attention during the briefing . Yet even the “big” journalistic personalities on a first-name basis with “Sandy” and “Mike” had little or no access to the President in China.

If the press felt ignored, except at feeding time, they weren’t alone. The dissidents who asked to see Clinton, from Ding Zelin to Xu Wenli, didn’t get close. China’s high-priority guest was ensconced in a gilded cage known as Diaoyutai State Guest House. Guarded under the tightest possible security by legions of wuzhuang jingcha (Chinese People’s Armed Police), Clinton’s entourage could hardly entertain the idea of meeting dissidents. Originally the China World Hotel was proposed as the Presidential residence, but the Chinese side balked, ostensibly because it is not grand enough for an important foreign guest, but in fact because it is a building over which the government has less than total control.

An embassy official told me that the topic of a dissident meeting was discussed before the summit. “The Chinese went ballistic!” he said. “I think it’s obvious they preferred letting Clinton talk on live TV.”

Clinton’s pointed remarks on human rights were beautifully composed, but not matched in action, symbolic or substantive. Furthermore, there was a scripted, rehearsed feel to the whole exercise where Jiang and Clinton gave long rambling answers to a few short questions. Jiang, in particular, seemed to be reading from notes.

“I listened very carefully to what President Clinton said just now, and I noticed he made mention of the political disturbances that happened in Tiananmen in 1989 and he also told the history of Tiananmen...” Jiang said, segueing smoothly into the party line, pronouncing the crackdown as necessary for stability.

Clinton expressed his talking points with more verve and little or no reference to notes, highlighting his gift as a public speaker. Meanwhile Jiang held his own in the gentle exchange of rhetoric, and even bettered Clinton when it came to policy concessions. Clinton reiterated support for the Communist party line on Taiwan and Tibet as integral parts of China. He kept completely silent about alleged Chinese interference in American elections. In return, Jiang permitted him to make some oblique criticisms about a bloody crackdown that took place nine years ago. Never once losing his avuncular smile, Jiang introduced a note of humor, wondering out loud why it was that otherwise civilized and educated Westerners showed such an interest in the theocracy of Lamaism. Good question.

Each leader skillfully played to his own constituency, converting the question and answer session into a public relations exercise.

Jiang anticipated Clinton’s “controversial” comments with uncanny accuracy, as if he had been primed in advance. The Chinese leader has shown a limited willingness to face questions before, most notably after his speech at Harvard University on November 1, 1997, even though his handlers insisted, and Harvard complied, that questions be submitted in writing in advance. Jiang’s occasional candid comments raise an interesting question: Is he trying to say something not permitted by his government’s party line or just rising to the challenge of the American style Q. and A.?

In any case, the little gust of free expression on Chinese TV on June 27 did not go far. The following day the People’s Daily, Guangming Daily, and smaller papers such as the Beijing Youth News, parroted Xinhua News Agency’s orthodox interpretation of the event, saying that the two leaders “stated their respective views on human rights and Tibet.” The story was then dropped.

With so many news-hungry journalists frustrated by lack of access to Clinton, unable to speak the native language and restricted in their movements (taxi drivers were ordered not to take non-official traveling press to Beijing University and the Great Wall, for example), White House press-handlers tossed breadcrumbs of information that were lapped up. At the same time, it was not in the interest of the White House to tell all. If Berger and his colleagues had knowledge that Clinton and Jiang had rehearsed the press conference, they didn’t let on.

During the Q. and A. session that followed, I asked Berger if the White House shared President Jiang Zemin’s denial of the alleged Chinese campaign contributions to U.S. politicians as “absurd, ridiculous and sheer fabrications.”

He answered that President Jiang had conducted a thorough investigation and found no wrong-doing, as if that should be the final word on the matter. When I pressed him on this, he said, as for the U.S. side, “leave it to the courts.”

The overblown idea that Clinton’s candid comments on live TV constituted an important chapter in China’s history was circulated among the press corps and by and large accepted before a single Chinese listener had been consulted. The White House hyperbole shot from “historic” to “600 million Chinese” without any basis in fact. (The press office later admitted this to be a guess based on the number of TV’s in China. The gross overestimate of audience size failed to take into account the off-peak hours of the unannounced broadcast.) Whether or not the novel experience of hearing two presidents quip back and forth on live TV left a deep impression on the Chinese nation is difficult to measure.

A Reuters report filed on June 28 reflected the giddy mood at the Shangri-La generated by the imagined significance of Clinton’s remarks: “A broadcasting milestone,” wrote L. McQuillan. “The news conference was the talk of the nation.” The same Reuters report also gave new life to the old canard about the Great Wall being the only man-made structure “visible from outer space.” The Great Wall is hard to see from airplanes and far less visible from above than an ordinary highway. A similar misconception that appeared in reports of the traveling press was the alleged name change from Peking to Beijing in 1972 as reported in The Boston Globe and elsewhere. (There was no name change for China’s capital city, only a new orthography adopted by The New York Times around the time of the Nixon visit.)

ABC News, trying to assess the impact the Clinton-Jiang press conference had on the people of China, resorted to quoting a Chinese American in New York City who said it “was quite exciting for them.”

Even the veteran press corps based in Beijing, eager to test the impact of Clinton’s words, could do little better than to quote a taxi driver or acquaintance. As for the White House press, few could even communicate with their taxi drivers.

To be fair to correspondents in the field, some mistakes are added by the home office. Take the words attributed to former New York Times Beijing Bureau Chief Nicholas Kristoff, in The International Herald Tribune of June 29, in which the Chinese President’s given name is mixed up with his family name: “When Mr. Zemin met with Mr. Clinton in Washington last fall.”

When I got back to Cambridge, I thumbed through back copies of my hometown paper, The Boston Globe, to see how it covered Clinton in Beijing. First the front page headlines:

“Clinton hits mark in China, aides say.”

“White House sees goals realized.”

“In China, Clinton calls for freedom.”

And then the sources:

“An important moment in the transformation of China,” says Mike McCurry.

“Profound reverberations,” says the State Department’s Stanley Roth.

“Surprised by the degree of success,” says Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

“A step forward,” says David Lampton, White House consultant.

“Boffo summit performance in Beijing, say aides.”

“In Washington, analysts said...”

“Billed by aides as the centerpiece...”

“White House officials said.”

“Aides and analysts said…the most important victory came in the image of Clinton, beamed to a potential audience of some 600 million viewers.”

It wasn’t just The Globe. For the next two days, most American reports were full of White House-spun praise for Clinton. There were exceptions, of course, including the more sober accounts of Asia-based correspondents out in the field who dug for stories and interviewed Chinese wherever possible. The Globe’s regional correspondent Indira Lakshmanan did a good job of this, shadowing the presidential itinerary without becoming hostage to it.

American journalists have been criticized much in the past year for being judgmental about unproved allegations in the “gotcha” attitude of their work. Ironically, some of those who tried and failed to “get” Bill Clinton to come clean about his personal peccadilloes, such as Sam Donaldson, found themselves engaged in a new game of “gotcha” with the Chinese. “China is still a police state,” Donaldson reported just hours after arriving in Xian. And as I observed the press on June 27 in Beijing, there was something close to universal approval in the ballroom of the Shangri-La Hotel, where the American President was viewed as shoving a dose of “free speech” down China’s throat in a televised performance.

The White House Travel Office charged media organizations upwards of $15,000 to send each journalist on the trip. For that price journalists won the privilege of speaking in authoritative tones about Clinton’s “historic” reception—as seen on TV from a luxury hotel and without a shred of reporting on the streets of Beijing, let alone the provinces.

Please Take Me To a Dissident

The White House press center made available bilingual crib sheets to help restless reporters daring enough to leave the hotel on their own. Without speaking a word of Chinese, they could communicate with a taxi driver by pointing to the appropriate line:

“Please take me to:

Shangri-La Hotel

Diaoyutai State Guest House

China World Hotel

American Embassy”

Additional entries for the more adventurous at heart:

“Please take me to:

Beijing Zoo

Hard Rock Cafe

Silk Alley”

That’s expatriate Beijing in a nutshell. And for those Americans homesick for “real” food:

“Please take me to the nearest

McDonald’s

KFC”

Translated instructions were written next to an empty clockface. It was left blank so one could draw the minute and hour hands to express pickup time to one of Beijing’s taxi drivers.

Finally the indispensable:

“Please stop where we can go to a restroom.”

Philip Cunningham, a 1998 Nieman Fellow, studied Asian politics and culture at Cornell University and the University of Michigan and has studied and taught in India, Thailand, China and Japan. From 1983-89 he worked in China as a tour guide and interpreter for film and television crews, with credits including “The Last Emperor,” “Empire of the Sun,” NBC’s “Changing China” and BBC’s “Panorama.” From 1990-97 he worked in Japan as a producer at NHK and wrote for The Asahi Shimbun and Japan Times. His freelance interviews with Chinese dissidents have appeared widely in print and in documentaries, including “Gate of Heavenly Peace.” Currently a Research Associate at Harvard’s Institute for East Asian Studies, he is preparing for publication “Reaching for the Sky,” a memoir about everyday life in Beijing during the student uprising of 1989.

Philip Cunningham, a 1998 Nieman Fellow, studied Asian politics and culture at Cornell University and the University of Michigan and has studied and taught in India, Thailand, China and Japan. From 1983-89 he worked in China as a tour guide and interpreter for film and television crews, with credits including “The Last Emperor,” “Empire of the Sun,” NBC’s “Changing China” and BBC’s “Panorama.” From 1990-97 he worked in Japan as a producer at NHK and wrote for The Asahi Shimbun and Japan Times. His freelance interviews with Chinese dissidents have appeared widely in print and in documentaries, including “Gate of Heavenly Peace.” Currently a Research Associate at Harvard’s Institute for East Asian Studies, he is preparing for publication “Reaching for the Sky,” a memoir about everyday life in Beijing during the student uprising of 1989.