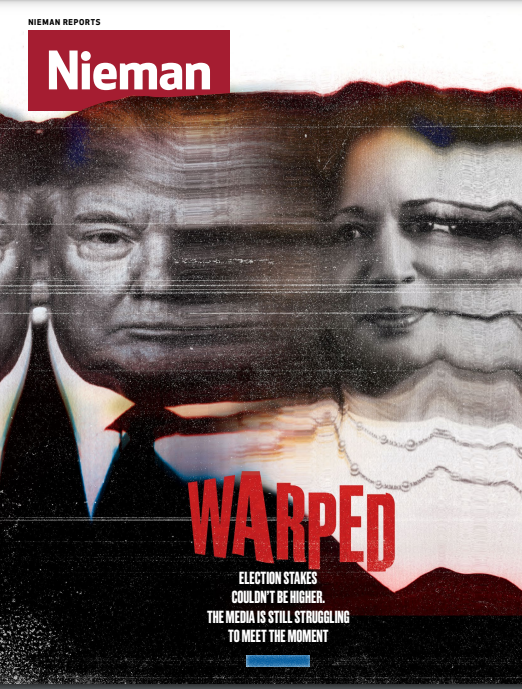

In February, just before I joined a Zoom call with Mark Graham, director of the Wayback Machine at the Internet Archive, I saw posts on social media that VICE News might shut down.

This would add to what has been a devastating time for journalism jobs. Publishers cut nearly 2,700 positions in 2023, and the cuts continued into this year. VICE reporters posted that their website might go dark within the next day. Stories spread detailing confused editors telling their teams they weren’t sure what management might do next. Freelancers posted instructions for saving pages as PDFs.

Graham’s work involves creating and keeping archives of websites. So, in the middle of our call, I brought up the rumors about VICE.

“I wrote it down, I’m on it,” he said. After we hung up, I saw the news: VICE would stop publishing to its site. Later, Graham told me his team “initiated some specific one-off archiving efforts” on the VICE website and other channels like YouTube, to save their articles and videos. This is on top of an extensive amount of archiving that’s already been done and continues to be done as part of the Internet Archive’s operations. “The fact is we have been archiving VICE all along,” Graham wrote. A visitor to the Wayback Machine can browse through thousands of snapshots of the VICE website, going back years, seeing the site as it was at various moments in time. Had the owners of the site shut it down completely, the Internet Archive would be the best — but incomplete — record of years of digital journalism.

The situation with VICE is increasingly common — not just the loss of journalists’ jobs, but the imperiling of archives at their source. When the short-lived news site The Messenger ran out of money this year, all of its story URLs redirected to a static page. The day after the VICE announcement, the owners of DCist, a local news outlet I wrote and edited for, announced it would shut down. A redirect on the website made all of DCist’s past stories inaccessible, until outcry from current and former staff (including me), readers, and several elected officials spurred management to keep the dormant site online for at least one year.

“Pretty much every place I've ever worked has dissolved,” says Morgan Baskin, who worked at DCist and previously at VICE. “Every time I publish a story I'm particularly proud of, I immediately PDF it just knowing how quickly things change.”

The closure of news sites underscores just how fragile the history of digital journalism is. Archiving wasn’t perfect in the analog days, but publishers held onto back issues for history and for reference. Baskin remembers a storage room in the Washington City Paper’s offices that held a copy of every past issue. “Somehow that is the safest and most comprehensible I’ve seen of somebody attempting to preserve the history of a publication,” she says.

Few publishers actively maintain archives of their digital-born news. A 2021 study from the Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri found that while no one was deleting their work, only seven were actively preserving everything. Most newsrooms — even those in strong financial shape — relied on their content management system (CMS) to keep stories online in perpetuity, “which is not a best practice by any means,” says Edward McCain, digital curator at Reynolds. This kind of preservation isn’t often reliable. A new CMS or a server upgrade can break links or knock years of history into the digital dustbin. Sometimes stories simply become unreadable or inaccessible as browsers and other tools for creating and viewing content evolve. “The whole first wave of news applications and data journalism was built in Flash. … All of that's been lost, basically,” says Katherine Boss, librarian for journalism and media, culture, and communication at New York University.

Even if a publisher saves everything on their website, the historical record can still have gaps. The interconnectedness that defines the web and empowers widespread sharing of stories and ideas makes the process of preservation more complex. Social media sites purge accounts or alter their architecture without warning. Embedded tweets, images, and videos are reliant on the original poster and host to stay live. A Harvard Law School study found that a quarter of the external links in New York Times stories have broken and no longer point to what they pointed to at the time of publication — a problem called link rot.

“It’s not that somebody's out there trying to get rid of the content,” McCain says. “It just happens as a function of some of the systems we developed.”

Whether they’re created by accident or not, holes in the record create openings for bad actors. A cottage industry has sprung up to buy the URLs linked to in news articles and fill them with ads. If a site closes down, its domain name can go up for sale to the highest bidder. Years after it shuttered, The Hairpin, a website led by women writers, resurfaced as a clickbait farm populated by AI-written articles. Feminist essays, humor pieces, and writing from Jia Tolentino, Jazmine Hughes, and other notable journalists have been replaced by stories like “Celebrities All Have Little Real Teeth Under Their Big Fake Teeth.”

Beyond broken links and scams, not having a record of digital journalism “is a direct threat to our democracy,” McCain says. In 2015, when Donald Trump was campaigning for president, he claimed to have seen thousands of people celebrating in New Jersey on Sept. 11, 2001 as the World Trade Center towers collapsed. Fact checkers debunked his claim by scanning local news archives. A record of reporting can be the answer to disinformation and a vital tool for accountability. “We’re not just talking at a national level, but we're talking about things like, the city council had issued these bonds for a water treatment facility and made certain promises and made certain projections. Did that work out? Do we know the details of what was told to us five years ago?” McCain says. “That's important stuff.”

In the weeks after DCist’s closure, Washingtonians shared memories of their favorite stories on social media (they couldn’t share links). There were investigations, including some into DCist’s owner WAMU, and years of day-to-day coverage of the city government — a beat that has seen fewer writers dedicated to it from other outlets. Many of the memories, though, were the features, the small slice-of-life stories. “There were stories about people's pet ducks wandering around the wharf … and the cherry blossoms and just all the little things that, over time tell the story of a place,” Baskin says. This is the power of having years of local journalism available to a community. It’s “a cumulative effect of all of these tiny stories that independently don't seem that important, but braided together, become so significant.”

A site doesn’t have to shutter for information to be lost in the routine operation of modern newsrooms. Live blogs are a standard way of covering breaking news, but updates can be overwritten and disappear forever. Social media posts are often buried by algorithms and could be deleted by the platform. Many of the dashboards that newsrooms built to track Covid-19 cases have vanished. Other times, they sit frozen at the last update. Home pages change without a record of what stories were on top, and often these homepages are customized based on user behavior, so no one sees exactly the same page anyway. In much of the country, a person can visit their local library and see what the newspaper reported in their town 100 years ago. But if they want to see how their community dealt with the pandemic two years ago, they’ll need to piece it together from a variety of sources, and there will still be gaps.

“The condition of the modern web is to be constantly disappearing. And so, in order to fight against that, you have to be not just hoping for your work to remain, but … actively working day in and day out and making choices to preserve and to protect,” says Adrienne LaFrance, executive editor of The Atlantic. (In 2015, LaFrance wrote a piece about how a Pulitzer-winning investigation from the Rocky Mountain News had vanished from the internet).

The work of digital preservation is increasingly complicated, especially compared to archiving print. In 2022, The Atlantic announced that all of its archives were available online — every issue of the magazine dating to 1857 was readable for subscribers. The magazine did this by digitizing the text of each story and loading it into their CMS. For readability, the articles are presented the same way a story published today would be. For context, each article contains a link to a PDF showing how it looked when it first ran in print, so a subscriber can see what an article written during the Civil War looked like upon publication — including what ads ran next to it and how it was formatted.

“The condition of the modern web is to be constantly disappearing.”

— Adrienne LaFrance, executive editor of The Atlantic

Every digital story The Atlantic has published is online, too, but readers can’t necessarily see them as they looked when they were first published. In 2021, for example, the magazine stopped using the software that had powered and formatted its blogs in a section called Notes. The magazine kept the text from the posts, but their appearance changed with the technology. “We don't render pages in those former layouts anymore,” says Carson Trobich, executive director of product for The Atlantic. “It would be impossible for just a casual web browser to go and see them literally in the context when it was originally published.” Each Notes post now features a message saying the page looks different from when it was first published. “We can't anticipate what some current or future reader might be searching for in our archive, so we want to give them all of the context they might need to understand what has changed,” LaFrance says. To accurately render Notes would require The Atlantic to maintain software in perpetuity. But even then, web browsers and the devices that run them change, making it even more difficult to preserve the experience of using a website.

Saving digital news is an ever-changing proposition. If an analog archive is like a bookshelf, then a digital archive is “like a greenhouse of living plants,” says Evan Sandhaus, vice president of engineering at The Atlantic and former executive director of technology at The New York Times, where he was on the team that built TimesMachine, a searchable archive of Times stories. The technology behind TimesMachine makes it possible to search for and link to words and stories inside of scans of original Times pages. It’s a vast archive with millions of pages and mountains of metadata about each page powering this interactivity. At the heart of it are images of original newspapers, which are ink on paper. An archive of digital-born news would need to work differently. Not every story was made to display the same way. Some were programmed with style sheets and code that browsers no longer support, or that render differently on new devices. Digital archives “require somebody or some team to make sure that the software is still running, is still properly serving traffic, and is still compatible with the crop of browsers that are on the market,” Sandhaus says.

Libraries' archives of newspapers, be they in their original physical form, on microfilm, or saved as digital scans, are possible because each edition of a newspaper is self-contained as a series of pages. “Where does a website start and end?” Boss asks. “Is it the main page and the first level of subpages for the site, as well as the YouTube embeds? Is it all of the pages and the YouTube embeds and a copy of the browser that the site was built to be accessed on? Is it all of those things plus the software libraries and operating system that it was built using?”

The level of preservation required isn’t something small newsrooms are generally equipped to do. Perhaps the greatest challenge the internet brought to archiving news, greater than any technological shift, is one of resources — few outlets in today’s media business have the money to keep an archivist on staff, or even a full-time web developer who can make sure links don’t break. It’s difficult enough to keep journalists paid, and keeping their work organized and archived online in perpetuity is an expense many outlets can’t afford.

“I think pinning our hopes on the publishers to solve the problems [of archiving] has clearly failed,” says Ben Welsh, news applications editor at Reuters and a self-proclaimed amateur archivist. Welsh doesn’t work in archiving at Reuters, but he has a history of preserving journalism. He organized the preservation group Past Pages, whose projects include the News Homepage Archive, a record of millions of screenshots of news homepages from 2012 through 2018, hosted at the Internet Archive. “The hope [for archiving] lies in outside efforts,” Welsh adds. Those include the Internet Archive, which uses an array of software to crawl thousands of pages — news and otherwise — and saves snapshots. Often, the archive has multiple snapshots of the same page, and comparing them offers a glimpse at how a story or a site has changed over time.

“Where does a website start and end?”

— Katherine Boss, librarian for journalism and media, culture, and communication at New York University

“They're doing the Lord's work there,” Boss says. In addition to the general crawling it does of sites, the Internet Archive hosts the records of Gawker, which shut down after a lawsuit, and Apple Daily, a Hong Kong newspaper that shut down in 2021 after the Chinese government raided its offices and arrested its editor and chief executive officer. It also holds archives of sites that haven’t been imperiled by governments or wealthy enemies, but by the vagaries of the market and the uncertainty of the industry. The Internet Archive offers a subscription service for publishers who want to maintain extensive archives, and the homepage has a “Save Page Now” button for any visitors who want to make sure the Wayback Machine holds a snapshot of a specific URL — something any journalist can do with their own work. But not everything can be so easily saved.

“Some of the technologies that drive web pages are less archivable than others,” the Wayback Machine’s Graham says. This includes interactives, such as certain JavaScript-coded visualizations, that often pull information from multiple servers. This puts archivists in a race against technology; when a new way of coding websites to display information comes along, so must a way to preserve it. On a call with Ilya Kreymer, founder of the Web Recorder Project, he shows me Browsertrix Cloud, one of the open-source archiving tools WebRecorder has released. He tells it to crawl NPR’s website, and soon, the dashboard begins filling with thumbnails of NPR stories from that day. “What it's doing is it's loading each page in the browser, it's automating browsers in the cloud, and it's archiving everything that's loaded on that page, all the elements, all the JavaScript,” Kreymer says. Once it’s done, it produces a portable file that can be saved or sent around, and that effectively emulates the website, showing it exactly how it was — allowing users to use the page as it was originally published, using the interactive features and playing most embedded media. This is called a high-fidelity crawl.

These types of tools are making it possible to save work that might otherwise be lost, but they still face challenges as web technology progresses and makes the pages that need to be saved more complex and the crawling process more difficult. “As soon as we find a way to fix one particular thing, there's this other new thing that the web can now do,” Kreymer says. On the NPR crawl Kreymer made during our interview, the cookie options pop-up appears on each page, slowing down the process. These are the kind of hurdles that tools are getting better at clearing, but that still present problems for external archiving. Paywalls are another challenge because an automated crawler doesn’t have login information. Newer tools can use an archivist’s login to save paywalled pages, the way a library might save its own copies of a newspaper it subscribed to, but this raises questions of copyright if the pages are made public. “Generally speaking, paywalls are — what's the right word? — are the enemy of archiving. Is the word anathema, is that an appropriate word to use here?” Graham says, noting that he understands the need for sites to operate as businesses. But he’d still like to ensure the work is being saved in a repository like the Internet Archive. “If I had a hope, or a dream, at this point, it would be a compromise, where we would at least be archiving the title, the URL, and an abstract and related metadata for all news, even if it was paywalled.” Other sites, like Facebook, actively prohibit archive crawls, making preservation of news outlets’ posts on those platforms more of a challenge.

Some of these problems would be solved if newsrooms took a more active role in their archives — not only allowing archive crawls, but using tools to readily preserve pages, then making those pages available. While any individual journalist can make a PDF of their work or even save a high-fidelity crawl, these files aren’t of much public value if they’re not accessible. “I simply cannot fathom a world in which it's not the responsibility of publication owners to preserve the work of that outlet,” Baskin says. “If you're not interested in preserving history, get out of the business of journalism.” It’s not clear what will happen to the DCist’s stories after the website is shuttered. The DC Public Library has expressed interest in holding them. And WAMU is owned by American University, which itself holds the papers of journalists like Ed Bliss, a producer and editor at CBS News who worked with Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite, but no definitive plans have been announced.

Archiving doesn’t have to be as costly or as time-consuming to a newsroom as it may seem. Besides the increasingly advanced and automated tools for archiving, there is outside help. Boss notes that libraries and archives have long played a role in preserving news. (It’s not as if all that microfilm came directly from newspapers.) “We have the mandate, we have the resources, we have the human resources,” she says, suggesting that newsrooms could appoint someone to coordinate with a university or library to make sure work is being saved. Some European countries, Boss notes, have laws that require publishers to save their sites — even paywalled sites — for the national library.

All of this could stop the journalism being produced today from vanishing. But still, a lot of articles have already been lost. After scanning the NPR site, Kreymer showed me a crawl he made of my personal website. As we went through the scan, I saw Browsertrix was saving everything — every link, video, and audio embed. But, when it got to my portfolio, some of the links led to 404 pages — file not found. Later, I decided to replace these links with snapshots from the Wayback Machine, provided those sites had been crawled. Fortunately, they had been, if not, there would be no way to recover them. Even the most powerful archiving tool can’t save what isn’t there.