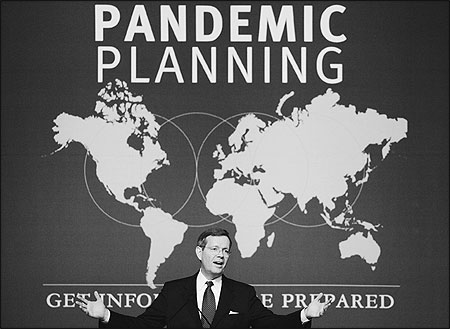

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Michael Leavitt addresses a summit of state and local officials in Los Angeles to discuss California's preparations for pandemic flue. March 2006. Photo by Damian Dovarganes/Courtesy of The Associated Press

Much has been learned about how people react and respond to disasters. From these experiences emerge lessons that can guide journalists in understanding better what they can expect to happen if pandemic flu occurs.

Dori Reissman, Commander, United States Public Health Service, and Senior Medical Advisor, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

What behavioral and social sciences can tell us about human behavior in a pandemic.

I challenge you, as journalists, to figure out how you can help us to manage fear in the public. I hope you haven't reached this point at which you either want to stick your head in the sand or run around and say the sky is falling. I hear the word "panic" all the time, and most of the time people don't panic. Panic really is about a loss of social order, a loss of internal order. Most of the time people are running around doing what they believe is self-protective. It's not panic, but it might not be social order. So let's be careful with our language and what we evoke because people have an image. When you say "panic," it evokes a feeling of being out of control. Is that what we want to evoke? Or do we want to give the message of how we can reel it in?

When we're thinking of behavioral health and emotional readiness, we don't have a ready-made framework of measures and countermeasures that are understood. That created some of the problems that we had in trying to disseminate this message. When we reach out to the different audiences, we find public trust is a big issue. If you don't have the trust, people aren't going to follow what you say to do.

The idea behind the public trust is if somebody is concerned about something and you don't address those concerns, they really can't hear your message. In government we focus on what is the right message. Can we recreate or procreate messages that are perfect to what we anticipate the issues to be? That's called push technology. We push out that message. But what if that message is out of sync to where the concerns are? What if the message has no receiver? Think about this as a football analogy, and how do you get the receiver to catch the ball if you haven't shown them how to do it?

And then what are the behaviors that you want to increase and what are the other behaviors you want to decrease in order to reduce risk? It's shaping behavior; it's not the government walking in and trying to control people. Instead, it's a sense of how people take personal accountability for their own safety in the context of the community's safety. The other part of the slippery slope is about people not coping well and making poor choices. There's a social and emotional deterioration, and with that comes dysfunction, and with that comes also a cascade of economic problems.

Human resource is the critical infrastructure. Yet we don't deal with what we house in our minds. We don't harden that. We harden our facilities, yet we really need to pay attention to this. I don't know how to obtain that kind of attention, but I know that you, as journalists, are a vector of it. You have a lot of impact, so I want to continue to challenge you.

How do we, in a noncrisis event, get the public used to and ready for critical messaging at critical times? How do we set that expectation and demonstrate it through the minor crisis that might be leading up to a more major crisis? That's where we will get a track record. In terms of trying to get people to reduce risky behavior, we aren't very good about following directions. We don't listen to our mothers. We don't listen to our doctors. So why should we listen to the government?

We've had different sets of experts get together and say what the empirical areas are that have evidence to support that good things will happen if you do them. That's what I'm going to call psychological first aid, and it has certain underpinnings — safety, calming, connection, efficacy and hope. Safety is about removing people from a threat. Calming happens when you want to lower the state of arousal so people can function, concentrate and take concrete steps towards what they need to do to protect themselves. People's basic need to connect with others and not be isolated needs to be attended to. Efficacy occurs when someone is capable of taking action on their own; when they do so as a member of a group, that's collective efficacy. The idea that the world is predicable and we will get through it, that's hope.

If journalists could take these five ideas and infuse them in their messages, I'd be very happy. Absent this, we don't have a leadership set up to handle grief. How do we manage massive grief and loss? How do we do ceremonies when you can't attend them? How do we support people who have lost a lot when you can't touch them? Continuity of operations goes way beyond business. It's continuity of life as we know it.

Sandro Galea, Associate Professor, Center for Social Epidemiology and Population Health, University of Michigan

A model of human behavior after disasters: Evidence from a systematic study of disasters during the past 50 years.

I want to offer you a framework for how to think about hazards and about what it is that shapes the consequences of these hazards and makes them into disasters.

There is no question that the first reaction to a disaster is fear and initial anxiety. People are afraid. They seek information. They do what is necessary to figure out how to save themselves. Information-seeking behavior is probably the primary modifier of what happens after these events. With the right information provided, there is a tremendous effort — usually guided by what we call pro-social behavior — to help others. That's called group preservation and represents stage two.

Stage three involves internalizing. We understand the psychological consequences much better than we do the behaviors, and many psychological consequences fall in place during this stage. With disasters, we talk a lot about emotional responses, about change in normal activities. We talk a little bit less about the notion of seeking redress and addressing vulnerabilities and strengths. After self-preservation and group preservation, this leads into efforts to try to figure out who is to blame and to do something about it by addressing the vulnerabilities and strengths that we have that resulted in that hazard becoming a disaster.

A perfect example of this is what happened at Columbine High School with the shootings there. It offered a very clear example of all four stages, including an emotional response, a change in normal activities — a change in everything they were doing in the school. Seeking redress by addressing vulnerabilities and strengths in terms of exactly what was happening in the school that resulted in this thing happening. A lot of blame was placed on everybody, ranging from violent games to the principal. And a lot of thinking went on about why this hazard — which in this case could be argued was the ready availability of handguns to these teenagers — became such a disaster.

Stage four is externalizing. This is the stage that unfortunately in this country we've become all too familiar with at this point, which is action against perpetrators, against those who are considered responsible. It's part of seeking redress. It's an effort for justice seeking. After the Oklahoma City bombing, President Clinton led the charge to seek redress. There was an epidemic of blame that followed, and then the task of addressing vulnerabilities began that, in theory, should have started preparing the country for other terrorist attacks. But one could argue that it was less effective.

Stage five is where we get the renormalization and adaptation. The group adapts to the threat. The normalizing of these new behaviors is seen as a direct response to the perceived threat.

With this synthesis of what populations go through after these hazards hit, I am hopeful it will help organize your thinking and help guide both your reporting and your questioning about these events.