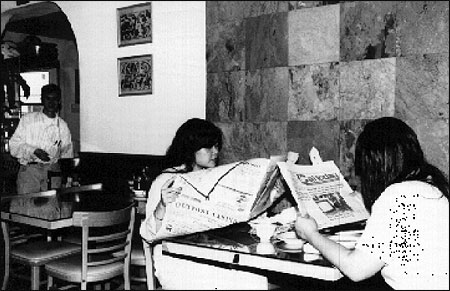

Vietnamese reading in San Jose, California’s Quang Da Café, a central distribution point for all Vietnamese papers. Photo by Blair Tindall.

A sign in the desolate parking lot identifies Calitoday. It is a three-year-old daily San Jose Vietnamese newspaper with seven staff members and an average circulation of 6,000. Editor Nam Nguyen answers the door in slippers, while columnist Hoa Pham types at one of three computers in the $500-a-month rented office. Inside, a Buddha statue, a bowl of pears, and an incense burner under a banner of Tibetan calligraphy comprise a shrine. Another Buddha, this one a lithograph, hangs over the drafting table where Nam Nguyen will finish his regular 16-hour work day by pasting up the paper at nine in the evening.

Across town the next day, Viet Mercury Editor De Tran relaxes over a cup of French roast after putting his paper to bed. Outside, sunlight dapples the San Jose Mercury News grounds. Since its inception nearly two years ago, his free weekly’s circulation has grown from 18,500 to 25,000. Tran’s 20 full-time Vietnamese-speaking staff members are employees of Knight Ridder, this country’s second-largest newspaper group, with 52 daily newspapers in 28 markets and a gross income of $3.2 billion last year.

In San Jose, some in the United States’s second-largest Vietnamese enclave regard the arrival of the Viet Mercury as a sign of its community’s prosperity. Others say the paper’s presence is killing its independent ethnic press by undercutting ad rates while its editorial content misrepresents the community’s culture and politics.

Until now, the few newspaper chains launching foreign-language papers set their sights on this country’s large Hispanic audience. Now, Knight Ridder’s San Jose Mercury News is courting another large ethnic group, in what Tran believes is a chain’s first foray into a non-Spanish-language ethnic paper. The Mercury News is taking advantage of a growing market that now makes up 10 percent of San Jose’s population: Vietnamese residents in this city have doubled since 1990 to 120,000.

The Mercury News is uniquely positioned to serve the Vietnamese. Since the U.S. trade embargo was lifted in 1994, the newspaper has had a Hanoi bureau. Also, by discounting ad rates for all three Mercury News publications (it also publishes a five-year-old Latino paper, Nuevo Mundo) the Viet Mercury is bolstered by its parent corporation while it develops a loyal advertising base.

San Jose’s Vietnamese are a marketer’s dream. Nearly a third of their households earn more than $65,000 per year and, as a community, they spend $1.5 billion each year. According to market research, San Jose’s Vietnamese read three or four newspapers per day and can choose among four local Vietnamese dailies and 10 weeklies. “At one time newspapers tended to write off immigrant populations as too small and poor to be of interest to advertisers,” said media analyst John Morton. “But the populations no longer are small, and many immigrants move up rapidly into the middle class and become attractive to advertisers.”

Reaching out to specific ethnic groups is not an entirely new publishing phenomenon. Newspapers such as The Washington Bee and The New York Age that were targeted at various black audiences were available during the 19th century. Indeed, the Ridder Group began in 1892 with Herman Ridder’s purchase of the German-language Staats-Zeitung. In 1976, Knight Ridder’s Miami Herald broke ground in the ethnic press with its El Herald, a few pages of material translated from and distributed with The Miami Herald. Today, El Herald has evolved into El Nuevo Herald, with a circulation of 100,000. The newspaper is operated and distributed separately from its parent newspaper; last year, its operating profit beat that of The Miami Herald. It is also the most rapidly growing of Knight Ridder’s 31 daily papers, according to its editor and publisher, Carlos Castañeda, and the fourth fastest growing of all U.S. dailies.

Comparing the Viet Mercury with El Nuevo Herald is only natural, says Tran. Both papers serve communist exiles who want their opinion represented in a dateline from home. Since the Vietnamese and Cubans are, as a group, wealthier and more politically powerful than many other immigrant communities, developing such markets might represent the latest niche strategy for newspaper chains to maintain their local markets.

But for these two immigrant populations, it’s become more than a David and Goliath war over attracting advertising dollars. Like many journalists who write for Cuban audiences, the Vietnamese writers brought adversarial traditions of news reporting with them, says Miami Herald publisher Alberto Ibarguen. They consider that the lack of presumed bias—the kind of objective journalism embraced by the Viet Mercury—actually presents a different kind of bias.

A vocal segment of San Jose’s South Vietnamese who, as a whole, constitute 65 percent of the city’s Vietnamese population, are upset with what they call the Viet Mercury’s glamorization of the North Vietnamese regime. “I used to respect [Mercury News publisher] Jay Harris, but now I am angry that he doesn’t respect our community,” said Tran Chi, former editor of Vietnam Family, a weekly that failed three months after the Viet Mercury’s inception. In a prepared statement, Harris asserts that the Mercury News set out to capture the Vietnamese market by creating an American-style newspaper, an approach that differs from Times Mirror’s 50 percent purchase in 1990 of the nation’s oldest Hispanic newspaper, Los Angeles’s La Opinion.

But American style hasn’t been universally accepted in San Jose. “It was friendly cooperation in L.A. They opened their hearts and doors to the community and invited them in,” said Tam Nguyen, editor of SaigonUSA. “But with Publisher Jay Harris and the Mercury, it’s slash and burn journalism.”

The Mercury News’s reporting by its Hanoi bureau chief, Mark McDonald, seems to anger just about everybody, whether they are American or native Vietnamese. “I try to keep my head down and the stories straight, and then I listen to everyone scream,” he said in an e-mail interview. Some Vietnamese, like Tran Chi, even accuse the Mercury News of editorially placating the North Vietnamese government to keep its bureau open.

Though its coverage is slanted by the ideology of its publishers, the independent Vietnamese press might have an edge in its newsgathering abilities. Calitoday’s Editor, Nam Nguyen, gets news and photos sent to him instantaneously via e-mail from correspondents all over Vietnam, whereas McDonald must request permission five days before he wants to make a trip outside Hanoi. Regions in Vietnam that are populated by ethnic minorities are completely off-limits to him.

Because of concerns such as these, a lot of Vietnamese set out to create their own news venues. And it is this voice, Tam Nguyen says, that the Viet Mercury is silencing. He blames the failure of two of San Jose’s 14 Vietnamese papers that were operating in 1998 on the emergence of the Viet Mercury. And he accuses that paper of unfairly undercutting ad prices to gain market share by selling full pages of ad space for $90 when he contends the market rate should be $400.

In a written statement, Harris defends his paper’s ad rates as competitive, saying they were not the lowest-priced Vietnamese newspaper ads available at the time. And De Tran points out that independent ethnic newspapers come and go frequently, so it is difficult to determine a direct correlation with the Viet Mercury’s success. Yet Tran Chi’s 6,000-circulation Vietnam Family shut down in the spring of 1998 after half of its advertisers defected to the Viet Mercury.

SaigonUSA still operates, but Tam Nguyen says that his publication lost 50 percent of its advertisers as its circulation dropped from 8,000 to 5,000. Total pages in SaigonUSA fell from 24 to 12, while in March of 2000 the Viet Mercury contained nearly 200 pages, 75 percent of which were advertisements. “We are bleeding,” says Tam Nyugen. “Newspapers are the single most important instrument to build a community,” he says. “We must do our job. When people in the community don’t read English, we must come to them.”

Media experts predict publishing chains will become savvier in the subtleties of connecting with ethnic markets. “I think the Viet Mercury signals a trend,” said Sandy Close, founder and director of New California Media, a San Francisco association of 140 ethnic news organizations. “Ethnic newspapers are caught between the ‘old media’ dailies looking rapaciously for niche markets and the dot-coms which increasingly threaten to replace newspapers as cable TV once did.”

Koreans, Filipinos, Malaysians and other Asian nationalities will likely bear individual scrutiny by chains. Together, Asian-Americans have a collective purchasing power of $101 billion and a rate of new business ownership nearly three times the national average, according to Kang and Lee Advertising, an Asian marketing firm. But they are not a monolithic ethnic category, and nationalities are fiercely committed to retaining their language and culture in the new world, unlike immigrants of 100 years ago, who encouraged their children to speak English exclusively. Kang and Lee find that Asian-Americans prefer to read in their native language at rates that range from 42 percent for Japanese to 93 percent for Vietnamese.

What is next? Probably not the Chinese, since Chinese-owned global media chains operating U.S.-circulated newspapers are formidable adversaries. But other Vietnamese communities in Houston, Dallas, San Diego, Oakland and Seattle, and Korean populations in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles are likely targets, says John Morton. In addition, California Filipinos and New York Asian Indians constitute substantial markets.

This language-based approach to reaching ethnic populations doesn’t always conform to the geography dailies have pursued. For example, Knight Ridder recently abandoned its Miami headquarters and headed for San Jose’s Silicon Valley, citing the necessity of staying current in the Internet economy. Now that Knight Ridder maintains 45 Web sites in various cities (each under the umbrella of its Real Cities outreach), the chain is positioned to reach ethnic communities, whether regionally concentrated or far-flung.

The ethnic press is watching closely. As director of a San Francisco-based ethnic press association, Close is not optimistic about the future. She has observed that dot-coms have not advertised in the ethnic press, and the San Francisco Chronicle’s recent list of 133 “best” Web sites didn’t mention a single ethnic Web page. But the Viet Mercury gets print subscription requests from Sydney, Australia to Biloxi, Mississippi as well as substantial hits on its Web site. Nam Pham, publisher of the failed Vietnam Family, recently spent $500,000 to develop his Web presence [vietnameselink.com], claiming this is one way to compete on equal footing with Knight Ridder.

California is now the Ellis Island for many ethnic groups. By next year, its white population is projected to become a minority, according to Mary Heim, the state’s assistant chief of demographic research. Finding ways to tap into an ethnic community’s spending power by reaching them through distribution of news is likely to be a trend among newspaper chains. But how well their coverage serves that readership, and what important voices might be silenced in the process, is an issue that ought to be moved onto the radar screens of journalists as this country’s ethnic profile changes.

Blair Tindall, a former business reporter with the San Francisco Examiner, is now an arts reporter for the Contra Costa Times in Walnut Creek, California.