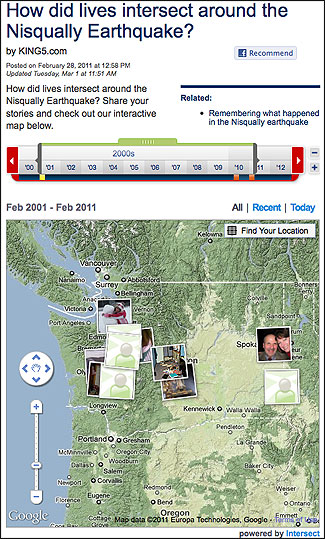

Seattle NBC affiliate KING-TV (www.king5.com) invited people to share their earthquake stories on Intersect.com.

When floodwaters rose in the Ozarks on April 25, the Springfield News-Leader in southwest Missouri tweeted: "Our photographers are running all over the area right now. Here are some of the pictures they’ve sent in."

When the recipients of this tweet clicked the link, they went to an interactive map on news-leader.com. Once there, they found thumbnails of flood photos tagged with places and times. Clicking a thumbnail revealed a panel with information about what other stories connect to this same time and place. These images—offered in this broader context—told a valuable story and they did so more powerfully than if each had been seen disconnected from the others. Glancing through the photos, readers could quickly learn whether any pictures were of their neighborhood or taken in a place where friends or loved ones lived.

They could watch the story as it was being told and in the ways they wanted to see it; the map gave them the ability to go to places of their choosing and be there in the time they wanted to be.

Stories put into context are more meaningful and are therefore more likely to be compelling. Context frames a story and imbues it with meaning. Amid a torrent of social media and with location-aware cameras, opportunities abound to be inventive in how context is conveyed and communities are formed. Interactive sites like one that I founded, Intersect.com, trace the contours of a story’s growth through the flow of time and place and offer viewers the chance to embed their stories into those being told by other members of this community.

I got the idea for Intersect while watching my daughter play lacrosse. It struck me that the best photos of her game might be taken by parents from the other team, none of whom I knew. I could try to exchange e-mail addresses, but that would be a burden to everybody—and it would do nothing for the parents who didn’t make it to the game but might enjoy seeing photos of it taken by strangers. It made me wonder if we could use the Internet as a place to share our photos and the stories behind them—and in doing so, create a sense of our shared place and time.

Intersect as Social Media

Tantalizing hints alert us to the great potential that digital media hold for journalists—and for journalism—in forming a wide variety of online communities. At The Washington Post, Michael Williamson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer, shows the effects of this country’s listless economy through illuminating photographs and accompanying short narratives. He took photos as part of his "Recession Road" project; the rest of the pictures are contributed by people who are participating in this online pictorial storytelling. People can view what Williamson describes as a "photocasting" journey across the United States as a website or as an interactive map.

These two interactive maps—Williamson’s "Recession Road" and the News-Leader’s Ozarks flood—were generated by Intersect, a digital storytelling platform my company created that enables people to form online communities based on experiences they’ve shared directly or indirectly. It does this by giving news organizations and others the tools to put stories into the context of place and time and develop chronological storylines.

It’s a form of social media, yet when content is placed on Intersect it sticks around. What a person contributes doesn’t vanish—stories from the past are brought back to life by anyone who wants to move through space and time to rediscover them. When I was in Philadelphia in mid-April I posted a story to Intersect about visiting the Liberty Bell as a tourist. When I clicked to see if any stories intersected with mine, I found out that Williamson had recently posted his own photographs from just across the Delaware River in Camden, New Jersey.

When someone comes to Intersect and wants to see stories done in April or stories from the Philadelphia area (or both), my Liberty Bell story will be there, as will my personal "storyline," which is a chronology of all the "public" stories I’ve published on Intersect. (If you are an Intersect member and I know you, then certain stories I’ve marked as private are yours to view.) Williamson’s story and storyline are there, too, with our coincidental overlap of time and place linking us at this intersection near the Delaware River. Even though we’ve never met, we can learn about each other by seeing our stories grow over time.

Having the ability to see this growth should be as important online as it is in our daily lives. In interactions we have with people and institutions, we form our judgments about them as we come to know and understand their stories over time, learning what they’ve done, where they have been, and with whom they interact. Intersect attempts to bring this dynamic to the Web.

The Washington Post uses Intersect as part of its social media engagement effort. Community members are invited to submit their own "Recession Road" stories and photos. The first time the newspaper extended such an invitation was during the Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert rallies on the National Mall in October 2010. That day, more than 100 people, including several Post reporters outfitted with the Intersect iPhone app, sent their photographs and stories to the Post site.

These days Williamson uses an iPhone to take pictures, with the option of immediately uploading them via this app, or he can use his laptop and connect to Intersect.com. An Intersect map can be embedded on a news site, similar to YouTube videos. This is the route taken by news-leader.com, along with King5.com, the website of Seattle’s NBC affiliate. For two mapping efforts, the King 5 newsroom invited sports fans to share stories around an NFL playoff game and then encouraged people to send in their experiences with earthquakes.

Digital media excel at mapping stories and at having people be able to locate themselves in them. News organizations employ them as visual ways to tell stories about events. The Associated Press put together a map and photo galleries about the end of April tornadoes that demolished parts of the South, while The New York Times mapped the path that the tornadoes took that week.

Intersect differs from these news organizations’ approaches since stories on any topic are created on it and they can be put there by anybody. (All of this happens without any cost to the producer.) Unlike custom maps, handtailored by a news organization for stories it covers, those generated by Intersect in response to photos and other stories are self-service. People are free to create a storyline on Intersect, invite people to share their photos and stories, and embed a map of the resulting collaborative storytelling experience on a website. These photos and stories can be tagged with the name of the publication, topic or a company name. Speaking of companies, when editors at the Springfield News-Leader decided to use Intersect, they just went ahead and embedded the Intersect code on their website. Only after they were up and running did we find out.

Intersect has been in development by a team of 10 for more than three years; it has been open for anyone to use since December. How it evolves will depend, to some extent, on the ways that journalists and others interested in creating communities use Intersect to further this purpose. As its developers, we imagine Intersect being a site where people move through time and places when they are drawn to a particular topic or story around which community has formed. It can also be a way for publishers—commercial and individuals—to get word out about their visual content by sharing with the community links to stories on their websites.

Yes, we imagine being surprised, too. With a place like Intersect, there will likely be ways we can’t think of now that people will find to cross paths with people they don’t yet know but with whom an experience creates a bond. Much is as unclear as it is exciting. Context matters, we know. Beyond this certainty, we are eager to discover how people will form communities around the core of what journalists do—tell stories.

Peter Rinearson, founder of Intersect, won a Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing for stories he wrote while on staff at The Seattle Times. He is a former Microsoft vice president who co-authored "The Road Ahead" with Bill Gates.