In the past decade, the rise of what is called “transitional justice” has been a significant phenomenon in foreign affairs and human rights. Today there is hardly a conflict situation where the quest for justice and the need to bring those who have committed mass crimes against civilian populations to task for what they did is not being advocated by humanitarian organizations or pushed forward by the United Nations. Setting up international criminal tribunals and stimulating national trials or truth and reconciliation commissions has become a common feature of the international community’s response to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Not surprisingly, Africa has become the main field of experimentation for international justice proponents. Deadly civil wars where civilians have been the main target of murderous armed groups have multiplied on the continent since the end of the cold war, prompting the international community to set up an unprecedented number of peacekeeping missions or humanitarian interventions. Weak and highly dependent states might have also provided “interventionists” with easier options than elsewhere in the Middle East, Asia or Central America. Thus, in the past 10 years, there is almost no transitional justice mechanism that has not been tested in Africa.

Following in the footsteps of post-apartheid South Africa, there have been truth commissions, either national or semi-international, in Ghana and Sierra Leone. Ethiopia’s “Red Terror” and then Rwanda’s genocide have led to mass national trials. It also resulted in the creation of a U.N. International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1994, following the one established a year earlier for the former Yugoslavia. Currently Sierra Leone is experimenting with a “mixed” court that has been hastily brandished as the “new model” for international justice. [A mixed court is comprised of both international staff and nationals.] And one can be reassured that the African continent will keep its leading position in this field as the newly created International Criminal Court (ICC) will probably take its first cases from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda.

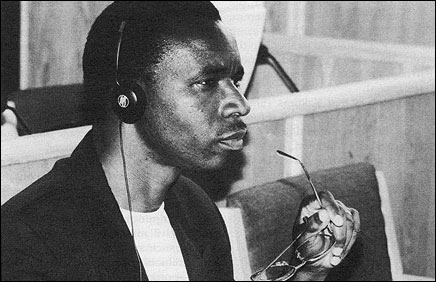

The founder of Radio RTLM, Ferndinand Nahimana, was sentenced to life imprisonment by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Photo courtesy of Intermedia.

Filling the Information Gap

Press coverage of these important judicial processes in Africa raise several concerns. The U.N. International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), which is based in Arusha, Tanzania, provides a particularly interesting case study. It is well known that the pace of justice is largely ill-adapted to that of the mass media. The ICTR’s serious mismanagement, excruciating slowness, and geographical isolation have only heightened this problem. In addition, there has been a constant (and not so hard to explain) diminution of interest in Africa among mainstream Western media. As a consequence, the ICTR has never been under close independent scrutiny from the mainstream international media. At the same time, local media have lacked the skills, the interest, or the means to organize such coverage.

In such a context, a new phenomenon occurred: To fill this information gap, international nongovernmental organizations (NGO’s) have assumed the role of independent, private media companies. Three of them, whose headquarters are located in the United States (Internews), Switzerland (Fondation Hirondelle), and France (Intermedia) have provided coverage of the ICTR since the beginning of the trials in 1997. Since 2003, only the Swiss one is still operating on a daily basis in Arusha while the American one has essentially moved to Kigali.

Such a situation, in which NGO’s, dependent on donors’ financial support, are in charge of reporting on trials with a highly political dimension, raises questions about their independence and the role they are playing as a watchdog. After several years of observing this coverage, it appears that, for the most part, the NGO reporting has proved to be seriously lacking in investigative, analytical and critical approaches. Notwithstanding a commendable effort to turn people’s attention to these trials and to transmit information back to the Rwandan population (living hundreds of miles away from Arusha), the reigning editorial policy has been driven more by a “project” mentality, common to NGO’s, than a journalistic one.

Yet there doesn’t appear to have been any pressure on these NGO’s from their Western donors, which are primarily governments. Obviously, these organizations have faced pressure from Rwandan authorities and, more disturbingly, from the tribunal itself. But whenever they gave in, it wasn’t due to pressures from those who were funding them. Thus, to a large extent, these organizations are engaging in what borders on self-censorship, deriving either from their principled reluctance to be seen as “troublemakers” (neutrality rather than impartiality is the key word for most NGO’s) or their possible interest in developing other projects elsewhere, including in partnership with organizations or powers that have stakes in these international tribunals.

While it may seem churlish to criticize these NGO’s for filling the information vacuum left by mainstream media’s withdrawal from these issues and regions, it is important to remember that their agenda is not the same as traditional media companies.

Sierra Leone provides a slightly different situation. Unlike the ICTR, which has enjoyed some specialized journalistic coverage, the Special Court here, whose trials started in June 2004, is only covered, on a permanent basis, by local media. Surprisingly, no information-focused NGO like the one in Arusha has opened any project in Freetown relating to the court’s activities. In a country where the local press suffers grave economic and ethical problems, as well as a lack of journalists trained in court reporting, the Special Court—which is principally funded by the United States, The Netherlands, Great Britain, and Canada—lacks any independent international watchdog. Only one international NGO, the International Center for Transitional Justice, has been closely monitoring the Special Court workings from the beginning. But it doesn’t aim at providing a public and independent journalistic coverage of the trials. Thus it cannot replace the press as a watchdog.

Lack of Democratic Control

This situation in Sierra Leone highlights a more serious problem facing the development of international justice on African soil. In the absence of a professional and independent press putting these tribunals under constant and consistent scrutiny, there is a lack of necessary democratic control. The experience of the ICTR and the Special Court for Sierra Leone show that these tribunals, like any bureaucratized and political institution, can become authoritarian, abusive, or corrupt once they realize that they have limited accountability.

Indeed, these courts differ from judicial systems in democratic societies by the fact that judges—not a legislative body—write the rules of procedure and can amend them at will. This has led to some rather unchecked practices that would be seriously questioned in democratic legal systems. With no counterbalancing legislative body, with state donors focused mainly on budgetary issues, and with human rights organizations reluctant to criticize institutions they helped create, there is an obvious need for independent press scrutiny to hold these tribunals accountable. This is perhaps more likely to come in an efficient manner from a combination of specialized international media and training programs—giving practical tools to investigate the workings of a court—for local journalists covering such institutions that deal with their own history.

Thierry Cruvellier, a 2004 Nieman Fellow, is the editor of International Justice Tribune (www.justicetribune.com). He covered the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda between 1997 and 2002 and the Special Court and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Sierra Leone in 2003.