Look back 23 years to the day when President Ronald Reagan was shot to find out why there are so many fewer staff editorial cartoonists today. When word reached cartoonists, they got to drawing so they could share the shock and outrage with readers in the next day’s newspaper. Back then, I was freelancing with the Daily Breeze, a suburban daily in the Los Angeles area, so I called to ask if they wanted a cartoon. And, of course, they did. Had they waited to use a syndicated cartoon, it wouldn’t have been published for at least two days, assuming they paid the Federal Express overnight rate.

Leap many years forward to the day when terrorists flew planes into the World Trade Center, Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania. Newspaper editors didn’t need a freelancer; they didn’t even need a staff cartoonist. A stream of editorial cartoons arrived via the Internet almost before the cartoonists’ ink was dry. And the editor had a large number of images to select from since newspapers often “subscribe” to receive the syndicated work of many cartoonists. One thing was certain: Whatever image was selected, the same cartoon would appear the same day in the cartoonist’s own newspaper and potentially in other papers in which editors also decided to “buy” the right to publish it.

Today, with the syndication market in editorial cartoons becoming saturated with cheaper products, cartoonists are still pining for national exposure and going the route of syndication to achieve it. This is understandable; they grew up seeing their role models published in the pages of their local newspapers as well as in the weekly round-ups. So the lure of syndication holds strong sway with cartoonists, even though their potential base salary as a staff cartoonist would far outstrip income they can make with syndication and reprints.

The Local Connection

Given these market-driving dynamics, editors of newspapers don’t have much motivation to keep an editorial cartoonist on staff. Yet the argument can—and should—be made that it is the newspaper’s best interest—editorially and commercially—to provide its readers with a connection to local issues, not only with reporting but also with the cartoons it carries. No syndicated cartoonist has the ability to tap into local issues or a community’s mindset.

If the role of a cartoonist is viewed as being like that of a columnist—some-one whose work truly engages readers—then local cartoons are essential. As a staff cartoonist with The Birmingham (Alabama) News, my cartoons provide another opportunity to carry on a conversation with the people who live here. And if I don’t cartoon about the foibles and squabbles over local and state issues, who will?

The late Pulitzer Prize-winning editor of the editorial pages of The Birmingham News, Ron Casey, used to half joke, “Cartoonists are expensive, and they’re a lot of trouble.” Thank goodness Ron and the rest of the management of this newspaper believe the expense is worth the trouble.

Each morning I read the newspaper to see if there is a local story that warrants a cartoon. Only when I decide there isn’t do I move on to national and international issues. This is not to argue that local news always trumps the use of national or international events. On September 12, 2001, it would have looked darn stupid if the cartoon on The Birmingham News editorial page was about a sewer bond issue.

At the end of each year I make two stacks of my cartoons: one contains national issues, the other holds the local ones. With the exception of 2001, every year I have worked for The Birmingham News the local stack is at least 20 percent higher.

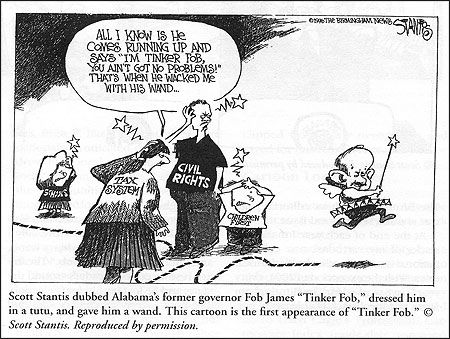

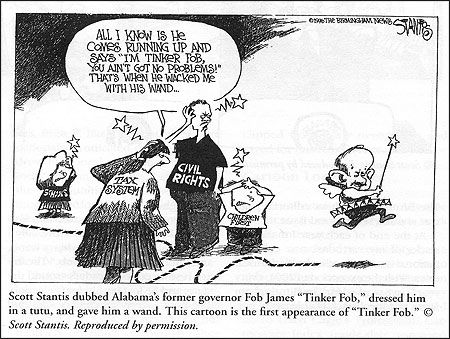

When our former governor, Fob James, became more and more silly I dressed him in a tutu, gave him a wand, and dubbed him “Tinker Fob.” The image resonated with readers around the state, and he lost his bid for reelection. The next governor’s chief of staff told me the “Tinker Fob” series had much to do with James’s defeat. That is the highest praise for any editorial cartoonist to receive.

As with so many things, there’s a middle road on which cartoonists can travel. Through the Copley News Service, my cartoons are syndicated to more than 400 newspapers, and I also do one cartoon a week for USA Today. I like to think I have something of a national reputation as an editorial cartoonist. I cherish this. But even more important to me is the reputation I have among my newspaper’s readers in Alabama.

Scott Stantis is editorial cartoonist for The Birmingham News, a weekly contributor to USA Today, and a syndicated cartoonist with the Copley News Service. His new political comic strip Prickly City was recently launched by Universal Press Syndicate. He is a past president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists.

Leap many years forward to the day when terrorists flew planes into the World Trade Center, Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania. Newspaper editors didn’t need a freelancer; they didn’t even need a staff cartoonist. A stream of editorial cartoons arrived via the Internet almost before the cartoonists’ ink was dry. And the editor had a large number of images to select from since newspapers often “subscribe” to receive the syndicated work of many cartoonists. One thing was certain: Whatever image was selected, the same cartoon would appear the same day in the cartoonist’s own newspaper and potentially in other papers in which editors also decided to “buy” the right to publish it.

Today, with the syndication market in editorial cartoons becoming saturated with cheaper products, cartoonists are still pining for national exposure and going the route of syndication to achieve it. This is understandable; they grew up seeing their role models published in the pages of their local newspapers as well as in the weekly round-ups. So the lure of syndication holds strong sway with cartoonists, even though their potential base salary as a staff cartoonist would far outstrip income they can make with syndication and reprints.

The Local Connection

Given these market-driving dynamics, editors of newspapers don’t have much motivation to keep an editorial cartoonist on staff. Yet the argument can—and should—be made that it is the newspaper’s best interest—editorially and commercially—to provide its readers with a connection to local issues, not only with reporting but also with the cartoons it carries. No syndicated cartoonist has the ability to tap into local issues or a community’s mindset.

If the role of a cartoonist is viewed as being like that of a columnist—some-one whose work truly engages readers—then local cartoons are essential. As a staff cartoonist with The Birmingham (Alabama) News, my cartoons provide another opportunity to carry on a conversation with the people who live here. And if I don’t cartoon about the foibles and squabbles over local and state issues, who will?

The late Pulitzer Prize-winning editor of the editorial pages of The Birmingham News, Ron Casey, used to half joke, “Cartoonists are expensive, and they’re a lot of trouble.” Thank goodness Ron and the rest of the management of this newspaper believe the expense is worth the trouble.

Each morning I read the newspaper to see if there is a local story that warrants a cartoon. Only when I decide there isn’t do I move on to national and international issues. This is not to argue that local news always trumps the use of national or international events. On September 12, 2001, it would have looked darn stupid if the cartoon on The Birmingham News editorial page was about a sewer bond issue.

At the end of each year I make two stacks of my cartoons: one contains national issues, the other holds the local ones. With the exception of 2001, every year I have worked for The Birmingham News the local stack is at least 20 percent higher.

When our former governor, Fob James, became more and more silly I dressed him in a tutu, gave him a wand, and dubbed him “Tinker Fob.” The image resonated with readers around the state, and he lost his bid for reelection. The next governor’s chief of staff told me the “Tinker Fob” series had much to do with James’s defeat. That is the highest praise for any editorial cartoonist to receive.

As with so many things, there’s a middle road on which cartoonists can travel. Through the Copley News Service, my cartoons are syndicated to more than 400 newspapers, and I also do one cartoon a week for USA Today. I like to think I have something of a national reputation as an editorial cartoonist. I cherish this. But even more important to me is the reputation I have among my newspaper’s readers in Alabama.

Scott Stantis is editorial cartoonist for The Birmingham News, a weekly contributor to USA Today, and a syndicated cartoonist with the Copley News Service. His new political comic strip Prickly City was recently launched by Universal Press Syndicate. He is a past president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists.