“Facebook is a bit like that big dog galloping toward you in the park,” said the late New York Times journalist David Carr, bemoaning the influence the social media giant has had on publishers’ distribution—and, in turn, monetization. “More often than not, it’s hard to tell whether he wants to play with you or eat you.”

Now, Facebook has an even bigger, faster-encroaching dog for publishers to grapple with: messaging.

Facebook’s Messenger and WhatsApp products now process a combined 60 billion messages a day worldwide. As an emerging medium, messaging is bigger than even Facebook. It’s the most widely used smartphone feature in the U.S., and it’s already taking a bite out of social media. As of the beginning of this year, according to Business Insider’s Intelligence Reports, the top four messaging apps—WeChat, Viber, Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp—have already eclipsed the top four social networking apps—Twitter, Linkedin, Facebook and Instagram—in their aggregate monthly active users.

This rapid growth is also poised to leave the rest of the mobile app ecosystem in the dust. According to eMarketer, more than 1.4 billion consumers were using messaging apps by the end of 2015; that’s 75% of all smartphone users and an increase of 31.6% over the previous year. And that number has grown rapidly since. As of this week, Facebook Messenger has already amassed 900 million users on its own. At a time when most smartphone users download zero apps per month and a quarter of all downloaded apps are abandoned after a single use, users are spending an average of 200 minutes a week on WhatsApp.

So, this is clearly a medium we should pay attention to. But how should publishers and news organizations play with it? To answer that question, we need to grasp what it is about messaging that’s allowed it to become pervasive, so that we can gain a better understanding of how content could fit comfortably on it.

Why Messaging Is Different

Text messages—the ubiquitous kind that are primarily used by consumers on their mobile devices—more aptly mimic the fluidity of human communication than other digital forms. The technology embedded in text messages sits in the background versus in your way. For instance, you can respond to a text message immediately or whenever is most convenient for you. It doesn’t require conversing parties to be available simultaneously, as a phone call or video chat does, nor does it assume that people would rather correspond asynchronously, as with email.

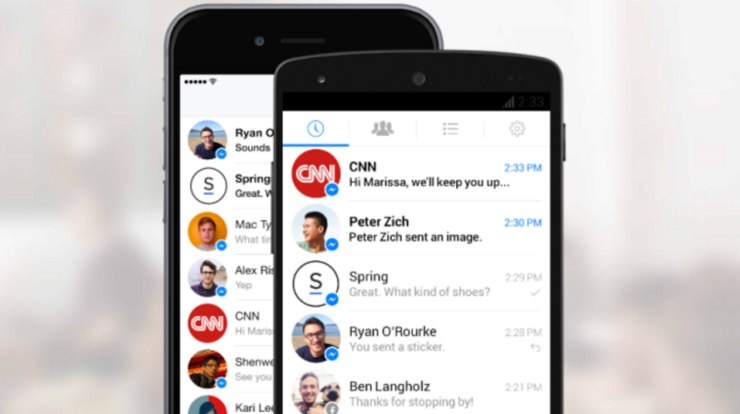

Text messages also offer a better representation of a person’s relationships by focusing on long-term conversations. Messages are typically organized in a list form that is automatically updated every time you interact with it. The people you talk to most frequently and recently at any given moment surface at the top of that list. You don’t have to manually program and repeatedly update the list in the way you may have back when you added your friends and family members to phone-based speed dial, or in the way you need to tell Facebook which friends are closer to you than others, a status that can change from time to time.

Also, in the context of the text message thread, a message you receive carries the expectation that you will engage with it. In this fundamental way, messaging differs from push notifications or alerts, which instead serve to simply broadcast information. The expectation with an alert is that as soon as you interact with it, it goes away. As soon as you interact with a text message, it sits at the top of your messaging list.

This focus on fluidity and conversation allows text messaging to more adequately fit the demands of our dynamic circumstances and relationships than other forms of digital communication. To successfully engage with the medium, therefore, publishers should harness these unique features that have made messaging powerful.

Cost Center or Revenue Stream?

Publishers will also need to know if messaging offers a clear path—or at least a dimly lit one—to monetization in order to see how widely they can experiment and whether this new outlet will represent a new cost center or revenue stream. While it's too early to tell, there are a few unique related aspects that are potentially promising.

By virtue of it living on your phone messaging is a natural access point to both your social and mobile data.

By virtue of it living on your phone, natively harnessing an ongoing memory of your conversations and serving as the best digital representation of your relationships, messaging is a natural access point to both your social and mobile data. For instance, Facebook Messenger is aware of your identity, social graph, location, conversation history and more. This ongoing memory—coupled with the fact that users are already becoming increasingly comfortable with making payments on their mobile devices—positions in-messaging payment services as potential facilitators of paywalled content. Once they set up their relationship with a service like Stripe or Facebook Messenger’s native payments feature, users can theoretically convert to paying subscribers with a quick text versus detailing their personal and financial information at every point of sale. This could make payments via messaging more effortless than they are to facilitate via websites.

This unique access to data also allows for messaging to support personalized and perhaps more appropriate user interactions with sponsors. As opposed to simply serving banner ads that may feel disruptive to the conversational experience, messaging apps have the potential to serve offers based on a user’s preferences. In this vein, Facebook Messenger revealed that it will be experimenting with sponsored messages.

Since preserving a personal tone is essential to the messaging experience, publishers and advertisers will likely explore this area cautiously, so we will hopefully see more intuitive exercises in commercialization using this new medium. For instance, since Facebook Messenger may already know of some services and companies you “like” via the data you have fed the parent platform over time, it will probably prioritize facilitating messages between you and those companies you already trust and may want to hear from. On the flip side, if an advertiser gets too noisy or feels irrelevant, you can easily block them from messaging you again.

Editorial Experiments

Before monetizing it, publishers need to test the medium itself. The most obvious, lowest-friction way to experiment within messaging platforms is to simply focus on them as new distribution points for content that’s already been created. Predictably, many big publishers have dipped their toes in this way; for instance, The Economist and Buzzfeed both experimented with the messaging app Line to push out news alerts that include links back to their respective publications for the full stories. Setting up this type of experience is similar to using Twitter to alert users; simply create an account on a text messaging app, allow users to subscribe to that account and either manually send out notifications or set up automated news alerts.

While easy and cheap to fulfill, this use case renders an experience that's closer to that of a billboard than a conversation, which is why The Economist deemed the exercise a “brand building initiative.” Since the user can’t really interact with the message, at best this experiment’s results will be commensurate with the effort, and at worst, they may mirror punishment by way of a slow release of the entire works of Shakespeare over text.

In taking a step towards experimenting with the conversational aspect of messaging, some publishers have run efforts like live editorial commentary. In this paradigm, a publication’s staff members chat amongst themselves—for instance, discussing a news event—and the subscribed audience can follow the conversation as it unfolds and maybe even participate in the discussion.

The Guardian hosted a WhatsApp chat alongside the GOP debates in December, and The Huffington Post ran a similar effort around various news topics on Viber. Another related use case involving editorial conversation is acting out a script. The BBC recently used Viber to tell the story of a real kidnapping in Mexico by having its editorial staff role play using actual quotes from people involved in the case.

As in the news alert use case, for this type of experience publishers need to create accounts on messaging platforms and build their subscriber bases. But this experiment also calls for extra time commitments from editorial staffers to write scripts and/or run the live chats. It can also require an outside trigger event, like a debate, to be happening concurrently on another screen that chat subscribers are also tuning in to.

Chatbots

While potentially engaging, hosting live conversations on messaging apps is resource-intensive and limited in its interaction with end users, as editors can’t scale themselves to respond to every user’s question or comment. This problem has prompted publishers to experiment with chatbots to allow users to interact with the news.

In the context of text messaging, a bot is an account operated by software in place of a person. Given a pre-prescribed set of rules a human editor makes, a bot can theoretically respond to a user in a way that mimics a human response. Quartz recently released a news app that sends a user a blurb about a story and employs a bot to ask the user to select between reading more about that specific story or moving on to the next story.

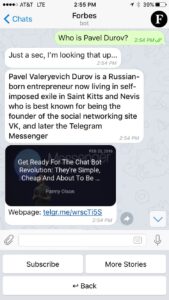

CNN created a similar bot on Facebook Messenger using the just-released Send and Receive API, and publications like Forbes and TechCrunch have created bots on the messaging platform Telegram using bot creator Chatfuel. Purple is yet another similarly powered bot that texts users with election news, allowing them to delve deeper into a subtopic within a message by texting back a pre-designated keyword (e.g., “Kasich”) contained within that original bot message. Powering these experiences relies on a diligent, combined effort of developing a bot (frequently via a third party) and dedicating editorial resources to writing short, conversational prose out of published stories.

In its current state, the news bot is a novelty that more closely mimics the experience of interacting with an automatic phone teller than talking to a human journalist. The seemingly endless loop of repeatedly hitting buttons or expressing keywords in order to get a response to a specific question can leave a user quickly fatigued. The underlying problem is that bots are essentially formulas created to handle a limited set of scenarios within a pre-defined framework, and they haven’t gotten to the point where they can manage massive banks of scenarios smoothly enough to handle every-day decisions.

This problem isn’t so different from why, with self-driving vehicles, “We’re clearly pretty close to making a car that can handle highway driving with no human input, since the range of possible events is pretty small,” says Benedict Evans, a partner at the venture capital fund Andreesen Horowitz. “But driving in central Rome or Moscow is an entirely different matter that needs an entirely different level of decision-making: What does that hand gesture mean?”

To handle the multitude of scenarios presented in an open-ended system like chat, we need a far more sophisticated bot that can scalably and quickly run decisions based on all potential user inputs, a form of artificial intelligence (AI) that can more holistically mimic human conversations.

The current limitations of chatbots haven’t stopped messaging platforms like Telegram, Kik and Facebook Messenger from launching their own bot ecosystems, nor have they hindered publications like The Washington Post from creating their own homegrown bots. The promise of true AI—an interaction framework that would allow news providers to offer each of their users a bespoke conversational experience at scale—is far too meaningful to give up on. That’s why, in tandem with releasing its limited-scope Send and Recieve API for bot creators, Facebook has also released Bot Engine, a system based on machine learning that can pave the way for more complex scenarios, like handling different variations of the same user questions.

AI-powered News

Looking to the future, you can imagine an AI-based chatbot that truly comprehends intention behind language, a bot that you can have long-term discussions with about the news the way you would with a well-informed friend. This intelligent bot could also fulfill the promise of voice-based products like Apple's Siri or Amazon's Alexa. It would both learn who you are and understand the content within stories enough to surface news you’d likely be interested in, whether or not you explicitly told it you were—or perhaps before you even knew you were. This type of bot would be promising in the sense that it may change the current rut we are in with digital news, a relationship which Twitter’s co-founder and Medium founder Ev Williams aptly describes as “stuck in … the idea that [the media people consume] is what they want.”

Will writers soon share the kind of power and influence over creating digital user experiences that graphical designers now have?

While we don’t currently have AI-powered news, we can start paving the way for it by crafting the right type of conversation-based frameworks for it. What’s exciting about this for writers and journalists is that the archetype text messaging is based on—broadly described as conversational user interface (UI)—is largely driven by exposing functionality through language; ‘designing’ a killer chatbot, therefore, relies at least as much on using the right kind of language as it does on a creating a great graphical user interface. Will writers soon share the kind of power and influence over creating digital user experiences that graphical designers now have?

Unlike websites and mobile apps, which rely heavily on navigational design and buttons to express breadth of coverage and direct users to the content they may be interested in, with chatbots “all of your features need to be reachable solely through words—so picking the right thing to say, and the tone of your dialogue with the user, is crucial,” explains Matty Mariansky, who created MeeKan, a calendaring bot for enterprise messaging platform Slack. This new role of language can empower writers to design experiences for messaging-based services. For instance, Mariansky hired dedicated scriptwriters to come up with more than 2,000 sentences to handle a meeting request.

Related Articles

Automation in the Newsroom

by Celeste LeCompte

With an interface that looks like a chat platform, Quartz wants to text you the news in its new app

by Joseph Lichterman

The New York Times’ new Slack 2016 election bot sends readers’ questions straight to the newsroom

by Laura Hazard Owen

While Mark Zuckerberg argues that the best messaging experiences will combine conversational and graphical UI rather than rely on words alone, the role of language as a form of user experience design becomes even more important when we start designing our bots to be flexible enough to work with both text and voice. When the bot is stripped of a screen altogether, as with services like Siri and Alexa, language is the user experience.

It wouldn't be far-fetched, therefore, to imagine a scenario in which journalists extend their writing skills and editorial judgment to not only cover stories, but design the channels through which these stories are distributed. These writers may also be critical to the development of an entirely new bot-influenced lexicon, introducing new words and phrases into our vernacular and, through them, new ways for users to interact with the news.

This type of shift—the ability for writers and publishers to design digital experiences with the same skill set used to hone their journalistic craft—could profoundly change their current shaky relationship with digital products and news distribution and, in turn, with their monetization streams and readers. Journalists don't have to sit back and watch this bot story unfold. There are no definitive paradigms yet, so we can help write the book on creating the most engaging experiences.