|

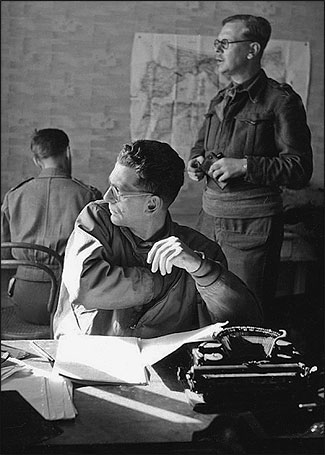

| Ed Kennedy, center, and an unidentified AP staffer react to the bombing at Anzio beachhead in 1944. Photo courtesy of Louisiana State University Press. |

Ed Kennedy’s War: V-E Day, Censorship & The Associated Press

Edited By Julia Kennedy Cochran

Louisiana State University Press.

201 pages. It should have been the apex of his illustrious career. But in some ways, it was the beginning of the end for Edward Kennedy.

The "scoop of the century"—Kennedy’s exclusive May 7, 1945 report on Germany’s unconditional surrender and the end of World War II in Europe—commanded front pages and radio reports around the world. It triggered celebrations everywhere.

But Kennedy, then Paris bureau chief for The Associated Press (AP), was swiftly suspended and months later quietly let go.

He stood accused by the Allied military of breaking an agreed-upon embargo, thereby causing a security risk.

His colleagues who had agreed to the embargo accused him of the biggest double-cross in journalistic history.

Kennedy stood tall against the charges all of his life. He contended that he had never put any life at risk nor had he double-crossed anyone. Instead, he said, he had done his duty as a journalist: He had stood up against political censorship.

Now we have his posthumously published memoir explaining it all in cool detail, how he did it, why he did it and why, finally—after all these years—the AP was moved to issue an apology this past May. Instead of standing up for a reporter who had performed to the highest journalistic standards, his bosses at the AP not only abandoned him, they fired him.

"It was a terrible day for the AP. It was handled in the worst possible way," said Tom Curley, the agency’s president and chief executive officer, in making the apology. Kennedy, he concluded, had done "everything just right."

The former foreign correspondent ended his days with his pride and journalistic principles intact, putting out a small, high-quality newspaper in Monterey, California.

Already suffering from cancer, he died in 1963 after being hit by a car. He went out doing what he loved to do.

"We can sell these pieces of dead trees only by creating the illusion that they are alive," he wrote in his final editorial. "This we attempt to do, with varying degrees of success, by headlines that grip the eye and written material that clutches the heart and soul of man."

Kennedy was attempting to do just that when, after six long years of war in Europe, the military was trying to muzzle the media—not for security reasons, but for politics.

News that would grip the very heart and soul of a world yearning for peace was being withheld.

Deal Breaker

The powers in Washington and London wanted to delay the announcement of war’s end for 36 hours to allow the Soviet Union to stage its own signing ceremony in Berlin and make people in its sphere of influence believe that it had delivered the death blow to Nazism, with contributions from other, lesser parties.

But Kennedy brought his signature alertness, sound judgment, and considerable spine to do what every good reporter should have done that day.

Kennedy had learned that while he and 16 other correspondents had agreed not to report the surrender they had witnessed at General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s headquarters until given the green light, a German radio station in Allied-occupied territory had broadcast the news—with Allied approval.

The embargo broken, the news out, Kennedy approached the military, demanding an explanation. Getting none, he paused to consider, then moved swiftly.

He called a colleague in the AP’s London office and told him the news: "Germany has surrendered unconditionally. That’s surrendered unconditionally. That’s official. Make the date Reims, France, and get it out."

He dictated about 300 words before the connection broke. Then he turned to his colleagues and said, "Well, now let’s see what happens."

All hell broke loose. The AP was bullied by the military, its operations in the European Theater shut down, and it quickly backed down—even before it had obtained the facts from its own reporter.

Military leaders weren’t the only ones to condemn Kennedy. The New York Times, which had used Kennedy’s story on its front page with multi-stacked headlines announcing the end of the war, also attacked him, decrying Kennedy’s report as a "grave disservice to the newspaper profession."

It was, of course, no such thing. It was one of the AP’s and American journalism’s finest moments and might well have saved lives.

"The war was over; there was no military security involved, and the people had a right to know," Kennedy told reporters when he landed in New York on June 4.

As his memoir recounts in telling detail, Kennedy knew the difference between censorship for political reasons and censorship for security concerns. As an AP correspondent for a decade, he had traveled across war zones in Spain, Italy, the Middle East, and Europe, and had operated regularly under the military censor’s blue pen.

But after careful consideration, he knew that military security was not involved. He and his colleagues had been hoodwinked for political purposes.

Today, in an age when government manipulation of information appears to be growing, when the shameful spinning of tales like those about soldiers Pat Tillman and Jessica Lynch are wrought from whole cloth, we need inspirational stories like Edward Kennedy’s more than ever.

As Kennedy reminds us, truth need not be the first casualty in war, nor the last.

All journalists owe Edward Kennedy a debt for distinguished journalism under fire.

Bill Schiller, a 2006 Nieman Fellow, is a foreign affairs writer for the Toronto Star.