Bodies in the lake. Bodies on top of the mall. Bodies hidden by city officials in a locker somewhere outside of town.

None of those rumors, which emerged in the wake of the April 27, 2011 tornado that hit Tuscaloosa, Alabama, killing 53 people, turned out to be true. But that didn’t stop them from spreading and, in some cases, being picked up and perpetuated by other media outlets.

During times of crisis, news organizations often find themselves up against a wall, balancing the demands of speed with a commitment to truth. That balancing act has never been more important—or more difficult—than now, when the competition of 24-hour news channels and the instantaneous nature of social media tools like Twitter and Facebook make newsgathering harder to do thoroughly and accurately.

Before the tornado, The Tuscaloosa News had been like many other small- to medium-sized newspapers in its use of social media. We had held at least one session, led by our own online staff, on the basics of using Twitter and Facebook to disseminate information. While our sports reporters were already proficient with Twitter, using it to update fans in real time on everything from game scores to player comments, only a handful of news reporters had Facebook pages or Twitter accounts. Several flat-out refused to use the new technologies, maintaining that the loss of privacy was not worth the effort.

But while most of us understood the usefulness of social media in the abstract, those methods were not seamlessly integrated into the newsroom’s operations and were used only sporadically, usually during breaking news events or to find sources for stories.

Emergency Drill

Two weeks after we held our first social media session, the tornado hit. It was a true test of how well we absorbed that recent information. With cell phones unable to connect calls and electricity down all over the city, including in the newsroom, the public had few ways of getting accurate information except through smartphones.

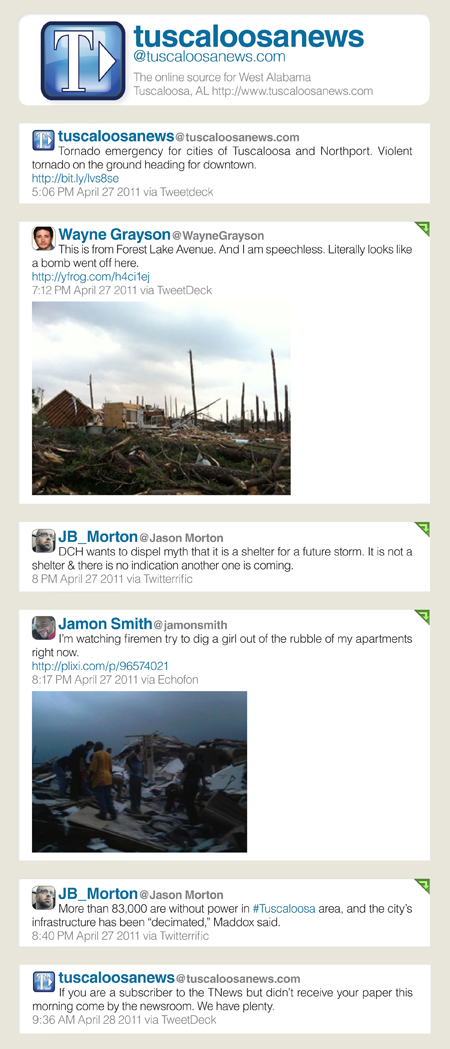

We discovered that a disaster is ready-made for social media tools, which provide the immediacy needed for reporting breaking news. Our reporters and photographers were on the street within minutes of the storm, tweeting and posting photos of the devastation.

The simple eloquence of a photo or a two-sentence tweet cannot be discounted: One reporter whose apartment was destroyed tweeted that fact, as well as a photo of firefighters digging a girl out of the rubble of what used to be his home. That stark detail brought home to readers—and to others in the newsroom—just how much the disaster had affected us all.

It was obvious that we were one of the few available media outlets that was both on the ground and could accurately fill the information hole. Reporters’ tweets and photos were aggregated to the paper’s website and Facebook page so people could see a continuous stream of information in the minutes immediately after the storm hit. Within the first 24 hours, we also created a Google Docs spreadsheet on the website to allow readers to post their own information, whether they were seeking missing loved ones or hoping to reassure their families that they were safe.

Such immediate information was also a service the public needed. People knew where the destruction was, what streets to avoid, and where to go for help. National Guard officials told editors afterward that they relied initially on the Twitter feed on The Tuscaloosa News website to show them where to deploy first responders.

After a deadly tornado, The Tuscaloosa (Ala.) News found that Twitter and other social media provided the immediacy needed for reporting breaking news and dispelling rumors.

The Debunking Blog

But while reporting the basics of a disaster—the number of dead, the streets that were impassable, available emergency services—is an easy task for skilled reporters, one issue cropped up that we could not immediately get a handle on: rumors. People seem to find it easier to believe rumors that they wish were true or that seem to fulfill a desire to hear the worst. That might explain why people continued to insist, days after the storm, that the city was hiding hundreds of bodies in a secret cooler even though the list of missing grew smaller each day, and, as the police chief repeatedly said, the city had no reason to hide the dead.

To that end, News editors created a blog to probe some of the more persistent rumors, tracking where they might have originated and talking with officials to get the facts. The format fit the nature of the story well. Tracking the rumors, with their ever-changing details, in print would have been slow and awkward, and the blog allowed us to update quickly. We also had the freedom to adopt a more casual tone to dispel some of the more ridiculous rumors, which made for more entertaining reading.

The blog format also gave readers a space to weigh in with their own evidence, which proved very useful. One of the more persistent rumors claimed that several children died while attending a party at a local Chuck E. Cheese’s that was destroyed. A manager at that restaurant was able to debunk the rumor by posting on the blog that she herself had closed it hours before the storm.

In the year since the tornado, News staffers have learned how to more actively incorporate Twitter and Facebook into their jobs. Reporters now tweet from meetings at City Hall with periodic updates on council members’ votes. They link to stories on Facebook to solicit feedback from readers.

Several times each day, we post advance versions of stories on the website, which allows us to take a more analytical, second-day approach with the versions of those stories for the print edition the next day. Our public safety reporter maintains a crime blog that she updates several times a day with reports of criminal activity. It has become one of the most widely read features on our website.

Incorporating social media and new technology continues to be a learning process for a news organization that still relies heavily on print to convey information. Like most other media outlets, we are still having conversations about how best to use these tools to enhance our newsgathering and how to handle the unique challenges that almost-instantaneous dispersal of news can pose.

But newsroom resistance to using these tools has largely died down, now that we have been confronted with stark evidence of how useful they can be to the newsgathering process and to readers who are increasingly ingesting news in untraditional ways.

Katherine K. Lee is city editor of The Tuscaloosa (Ala.) News. The paper won a 2012 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Reporting for its coverage of the tornado on April 27, 2011.