A blog about intelligent design written by Jeff Bruce, editor of the Dayton Daily News.

As I dropped my son off at school the other day, I spied one of those plastic fish affixed to the back of a sedan in front of me as we sat queued in the parking lot. This one had the word “Truth” inside a big fish devouring a smaller fish labeled “Darwin.” It served as an ironic counterpoint to a similar fishy display on my own dashboard, another big fish eating a smaller one with the words “Reality Bites” inside.

Our dueling fish are emblematic of the debate raging across the country over efforts to instill “intelligent design,” or I.D., into public school science curricula. Intelligent design is the controversial challenge to the theory of evolution being pushed by some social conservatives who seek to offer an alternative to Darwinism that is more compatible with the biblical story of creation. Intelligent design advocates argue the universe is so complex it can only be the consequence of an intelligent, guiding influence. Critics call I.D. mere creationism costumed to sneak past First Amendment prohibitions against church-state commingling.

As this article was being written, the state school board in Kansas was nearing adoption of a plan requiring that opposing views to the theory of evolution be taught. A federal court was hearing an intelligent design lawsuit in Pennsylvania, and in my home state of Ohio, where I am editor of the Dayton Daily News, the state board of education has already mandated that 10th graders be taught about the “evolution debate,” including competing ideas such as I.D.

I have been especially interested in the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania trial where 11 parents in the Dover Area School District filed suit in federal court to block the inclusion of intelligent design in the ninth-grade biology lesson plan. While a ruling in that court would have no direct bearing in Ohio, the judge’s decision could inform other courtroom battles as they erupt, which seems inevitable.

Reaction to the I.D. Coverage

I called Bill Toland, a reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, who has covered the trial, as part of my research for this article. I was interested in the feedback he received from his readers. Toland said he has postulated a new theory governing the speed of news as a result of his experience. “I call it the First Rule of Journaldynamics,” he told me. “The speed at which a story moves over the Internet is directly proportional to the number of times you mention ‘gun rights,’ ‘evolution’ or ‘liberal’ in your story.”

Like many newspapers, including mine, the Post-Gazette publishes reporters’ e-mail addresses and phone numbers with their stories. During the first few weeks of the Harrisburg trial, Toland was getting calls and correspondence from around the world. “It’s just remarkable the geography of the feedback,” he said, confessing “there were some days” when it occurred to him it would not be a “bad idea to drop the tag lines.”

While one might expect the majority of feedback to have come from I.D. proponents, Toland said he heard from both ends of the debate. His stories were dissected for liberal bias by the Discovery Institute, the Seattle, Washington think tank proselytizing I.D. as part of its “wedge” strategy that seeks to displace Darwin with “a science consonant with Christian and theistic convictions.” But he was also taken to task by liberals who objected that “paying attention to the I.D. crowd at all” falsely elevated the legitimacy of their arguments.

That matches our own experience in Dayton, where letters to the editor and e-mails have poured in from readers during the past several years as the state board of education debated whether science lessons plans should include challenges to Charles Darwin’s theories of the origin of life. The board finally settled on a compromise proposal to “teach the controversy.”

“Ohio is now ground zero for the explosion of creationism that is sure to follow,” warned Patricia Princehouse, a Case Western Reserve University evolutionary biologist, when the new lesson plans were adopted. Princehouse is an organizer of scientists opposed to teaching “intelligent design.” Given recent events, her warning seems prophetic.

Some background: It has been 80 years since the so-called monkey trial in that other Dayton—Dayton, Tennessee—where John Scopes was convicted for teaching evolution. That ruling was later overturned by the Tennessee Supreme Court, and in 1968 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it is unconstitutional to ban the teaching of the theory of evolution. You might think that would have settled the matter. Think again. When I Googled the phrase “intelligent design” in late October, I found 61,900,000 entries. Impressive. Not even Jesus Christ has those numbers (26,600,000), or Genesis (32,200,000). God, of course, is well represented on the Internet with 170,000,000 listings, but even He is overshadowed by “evolution” at 227,000,000 Google hits.

The idea of science trumping God in any setting sets some people’s teeth on edge. It underscores the arguments and courtroom battles playing out over whether “intelligent design” has a place in public school classrooms. Already bubbling, the issue heated up even more earlier this year when President George W. Bush was asked by a reporter if intelligent design should be taught. His answer, I thought, was nuanced. “I think that part of education is to expose people to different schools of thought,” he said. “You’re asking me whether or not people ought to be exposed to different ideas, the answer is yes.” But his words ignited a firestorm of commentary online and in the letters columns of newspapers.

Coverage Stirs the Debate

I blogged about Bush’s comments on my newspaper’s Web site, figuring it would be a natural to stimulate comments from readers. Little did I know. The debate my observations sparked among my blog’s commenters raged for four weeks and sometimes got ugly. A sample:

Spirilis: “The entire debate is about your faith, Jen. We simply want it kept out of the science classroom. I personally don’t care if you believe that space aliens originated life on earth but you have no right to teach your silly beliefs in a tax-supported institution. Worship whatever books you choose just quit trying to turn your fiction into my fact. I can accept that someone could want to remain ignorant but what is the benefit in keeping the future in darkness? Why do you hate the children so? ….”

Jen: “Awww, Spirilis! I expected more out of you than that! I gave you the debate you wanted and you ended it with a desperate attempt to attack my faith and my personal life; did you run out of things to say? What I gave you is science, accept it! Everything I said is true, you know it. If you think I am wrong, PROVE IT! You can’t. … Spirilis, you pick only specifics about what you want to hear, only when it supports what you want to believe, but then you ignore all other evidences, facts and truths that discredit your precious evolution …. As for your personal attack on me, I refuse to even dignify that with a response; that was just pathetic on your part. Great debate, Spirilis.”

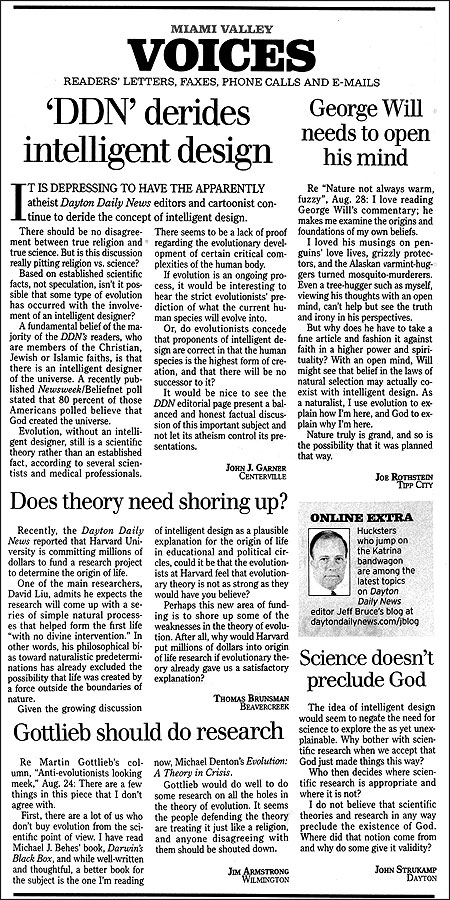

The I.D. debate also filled the letters columns of the Dayton Daily News. Some samples from just one day, September 2nd:

John Garner: “It is depressing to have the apparently atheist Dayton Daily News editors and cartoonist continue to deride the concept of intelligent design…”

Thomas Brunsman: “Recently, the Dayton Daily News reported that Harvard University is committing millions of dollars to fund a research project to determine the origin of life …. Given the growing discussion of intelligent design as a plausible explanation for the origin of life … could it be that the evolutionists at Harvard feel that evolutionary theory is not as strong as they would have you believe?”

John Strukamp: “The idea of intelligent design would seem to negate the need for science to explore the as yet unexplainable. Why bother with scientific research when we accept that God just made things this way? … Where did that notion come from, and why do some give it validity?”

Opinion vs. News Pages

The contention, raised by that last letter writer and echoed by reporter Toland’s liberal critics, that in an effort to be fair and balanced we risk distorting the picture by giving undue credence to I.D., is a slippery one. It presupposes a judgment of illegitimacy that most journalists would feel uncomfortable making for the news pages. The opinion pages, though, are another matter. We publish Leonard Pitts, Jr.’s syndicated column, which our readers rank among their favorites. Here’s his take on the question of whether students have a right to be exposed to all sides of the evolution issue, from his September 30th column:

“… for that argument to hold water, you must have more than one side. Where science and the theory of evolution are concerned, you do not. It is the overwhelming consensus of the mainstream scientific community that Darwin had it right. So pretending there is another ‘side’ to the question makes about as much sense as pretending there is another side to the Klan. It reeks of false equivalence, no-fault scholarship, judgment-free education, the bogus notion that all points of view are created equal and are equally deserving of respect.”

Irrespective of intelligent design’s legitimacy as a scientific theory, at some point numbers matter when it comes to news coverage. And proponents of I.D. know how to draw a crowd. This movement is arriving at a time when those of us in the news media are acutely aware of the public’s perception of liberal bias. We’re familiar with the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press study showing two-thirds of Americans agree that “in dealing with political and social issues, news organization tend to favor one side.” Moreover, a 2004 Gallup Poll found that 45 percent of the American people think human beings were created by God “pretty much in their present form” sometime during the past 10,000 years, a timeline that closely parallels the Old Testament story of creation but is at wild variance with the scientific fossil evidence.

Our newspaper’s instinctive response is to be careful, to be especially mindful of the need to be balanced. But Pitts’s objections of “false equivalence” are compelling. At what point in our efforts to be neutral in our news coverage do we risk becoming misleading? This is especially challenging with the First Amendment on the line and the role newspapers have carved out for themselves as protectors of the Bill of Rights.

Even when we strive for balance in our news columns, the passionate views expressed on our opinion pages can carry over to color perceptions of the overall newspaper. Earlier this year, the Dayton Daily News hosted a roundtable meeting with members of the community to explore their concerns about liberal bias. We followed the format established by the Associated Press Managing Editors (APME), which has pioneered the program. Steve Sidlo, the newspaper’s managing editor and a member of the APME board, and Assistant Managing Editor Jana Collier organized the conference. The feedback from participants, who were a self-selected group of critics, clearly showed that spillover from the opinion pages tinted their perception of the paper.

Interestingly, many of these critics admitted they “shopped” the paper for signs of bias, betraying their own foregone conclusions. Still they scored some hits—a headline here, a phrase in a story there—that those of us observing the discussion agreed added legitimacy to their criticisms. The presidential election, as well as hotly debated social issues (abortion, prayer in schools, gay marriage), was among the topics that fueled their perceptions of the paper’s prejudices. We left the roundtable discussion with a renewed determination to police ourselves more vigorously, understanding how easily we can undercut our authority with even the smallest lapses in diligence.

The good news is that our readers expect us to tee up controversial topics for discussion and that newspapers and their Web sites can and do provide useful and provocative forums for these conversations—with us and among our readers. In a world of multimedia competition, it is crucial that we position our newspapers and online sites as the ideal place for such debates to rage. In so doing, though, we should be mindful that while clearly distinguishing news and opinion in our print products is standard operating procedure, the lines can blur in the blogosphere. We need to be cognizant of this and the implications for the newspaper’s overall credibility. And we need to be mindful, as Toland discovered, that our audience is now worldwide, meaning, among other things, that there are more eyes than ever before examining us and holding us accountable.

For myself, I’ve taken that fish off my dashboard. There was a time when these sorts of decals could be viewed as friendly jousting. I think those days are gone.

Jeff Bruce, as editor of the Dayton Daily News, is in charge of the newspaper’s newsgathering and opinion page staffs. His weekly column is published on the News’s Sunday editorial page, and his blog appears at daytondailynews.com/jblog.