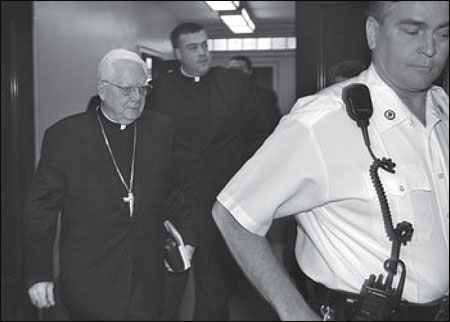

Cardinal Bernard F. Law departs Suffolk Superior Court in Boston in May 2002 after he gave his first deposition in the clergy sex abuse scandal. Pool photo by David Ryan/The Boston Globe via The Associated Press.

For the thousands and thousands of families involved, the clerical abuse scandal that exploded in Boston in January 2002 was a tragedy of unimaginable dimensions. For Catholics in America, the crisis was a massive blow to the faith and the institution they were raised to love. For journalists, it was something else entirely: a runaway freight train of a story that roared along with fierce—and sometimes frightening—momentum. Day after day, story after story, outrage after outrage, this crazy locomotive just kept tearing along. Many days, it felt like no one was in the driver’s seat.

It was a special challenge for me, a one-woman bureau assigned to cover six New England states for the Los Angeles Times. This ongoing tale of shattered trust and broken lives also gnawed at me as few news sagas have managed to do. The same month that lawyer Roderick MacLeish, Jr. produced documents detailing horrific violations of children by former priest Paul Shanley, my son Sam turned 12—the very age when so many victims of pedophile priests were stalked and savaged, physically and emotionally.

Grown men and women wept in my presence as they described alarmingly similar experiences with men who stole their innocence: men who called themselves “Father,” men who called themselves holy. My office is at home, and I share a wall with my son’s playroom. Some days, transcribing these victims’ accounts into fodder for news stories, I would hear Sam and a friend sharing the simple joys of childhood. Twelve is an age when boys boast machismo and vulnerability in equal measure. They tell dirty jokes at one moment—and, in the next, they role-play with stuffed animals. I am an old-hand reporter, so ancient that in the days of Linotype machines, I learned to read backward and upside down. I have covered dreadful stories of human atrocity. I like to think of myself as even-keeled and objective. But on these days, I wept, too.

This is how it started: For a sturdy corps of local reporters, peppered by the handful of national correspondents who call Boston their home, the year 2002 dawned in a courtroom in Cambridge, Massachusetts. A mammoth, muscular father pegged by his lawyer as a “gentle giant” was charged with beating another father to death following a dispute at a skating rink. The “hockey dad” trial, as this surreal scene soon became known, picked up its pitch and its pace each day—until finally, as the verdict was handed down, four reporters from People magazine were jockeying for seats in a minuscule courtroom already packed with news people squeezed between two families who made the Hatfields and McCoys look like kissing cousins.

This Thomas Junta trial was, in its way, a preview of coming Boston news attractions. That case ended on a Friday. The following Tuesday, in the same Middlesex county courthouse, the child molestation trial of former priest John J. Geoghan began.

Midway through the Junta proceedings, The Boston Globe published an extraordinary story. In painstaking and sensational detail, the Globe used court records to show that the Boston archdiocese knew all about Geoghan’s history as a pedophile priest. Rather than yanking him from the priesthood, local church leaders moved Geoghan from parish to parish—the “geographic cure,” as this practice is known. Rather than protecting young parishioners from a monster in a Roman collar, archdiocese officials aimed to safeguard the reputation of the church.

Let me say right here, loud and clear: Hats off to The Boston Globe. Some days—many days—it was frustrating and downright annoying to add the phrase “as reported in The Boston Globe” to stories I wished could have been fully original in content. But the Globe outran us all on this one, starting with its dogged fight to obtain damning documents the church kept hidden for decades. The Globe’s coverage was so thorough and relentless that at times I felt like a solitary runner competing in an uphill marathon against a relay team that never ran out of stamina, not to mention Gatorade.

I called my editors in Los Angeles the day the Geoghan story broke in the Globe. Heads-up, I said: Watch out for this one, it’s going to be B-I-G. Yeah, yeah, yeah, they said, barely suppressing their yawns: We have dirty priests out here, too. Besides, my editors countered, this guy Geoghan was only charged with one count of fondling a kid at a swimming pool. What kind of a scandal was that?

Just wait, I promised.

The Scandal Unfolds

Geoghan’s trial stretched through February. By March, I was writing about rumblings that Cardinal Bernard F. Law would step down. I broadened the scope to write about women in the church: How was the crisis affecting them? I went to New York to meet with some Jesuits, writers themselves, who debriefed me on the innuendoes of clericalism. I sought out victims’ groups in Boston and around the state. I stood on the frozen steps of a church in Worcester, waiting to talk to priests and worshippers there. I drove out to Leominster, in central Massachusetts, to watch a group of women charge their childhood priest with raping them as little girls. I tracked down “good” priests who were as angry and appalled as any of us. I tried to make contact with church officials and their lawyers. Call after call to the venerable Rogers Law Firm, long the counsel to the archdiocese, went unreturned.

All this unfolded in the face of dozens of other New England news stories. There was the murdered fashion writer, Christa Worthington. There were verdicts for the teenage killers of Dartmouth professors Half and Susanne Zantop. There were impending elections, Acting Governor Jane Swift’s latest antics, and the forthcoming corruption trial of Providence mayor Vincent A. “Buddy” Cianci, Jr.

But the church abuse locomotive kept steaming along. Chug, chug, chug: That was the sound of scandals breaking out in parishes all across America. Slam, slam, slam: That was the sound of the church perfecting the art of inaccessibility.

In April, Boston was the setting for what might have been a three-ring media circus. Instead it was a turning point that sped the scandal up still more. Looking every inch the circus impresario as he snapped his lapel microphone into place, attorney MacLeish filled a hotel ballroom with reporters and dozens of others who turned out to be abuse victims and their friends and family. The lights darkened and a 30-foot Power Point screen lit up. All we needed now were lions, tigers and cotton candy vendors.

But MacLeish delivered, mesmerizing the room with pictures and documents that made it clear that former priest Paul Shanley’s predilection for sex with children was no secret to church authorities. Journalists are notorious for our short attention spans. Fifteen minutes, and we start to fidget and reach for our cell phones. But what MacLeish produced was spellbinding. For almost two hours, the only movement from journalists was the furious scrawl of pens across notepads.

Never mind that my story the next day ran inside the paper. This was one of the challenges in a year-long story: making it fresh and new every day—and doing so for editors and an audience 3,000 miles away. Time after time I whispered the phrase “Page One candidate” as I pressed the “send” button to transmit the latest church-scandal offering. Time after time, I told myself: Forget about it, get this story in the paper, wherever it runs. That became my objective: advancing this amazing news organism, keeping up with it as it grew and morphed and mutated.

By the time the cardinal at last resigned on December 13th, an odd camaraderie had grown up. Journalists, protesters and counter-protesters all knew one another from gatherings outside the chancery or in front of Boston’s Cathedral of the Holy Cross. Lawyers got way too candid and victims shared black-humor jokes, along with copious quantities of tears. Rodney Ford, the father of one alleged Shanley victim, became so accustomed to my phone calls at his home that he would playfully shout to his wife, “Honey, it’s that pain in the ass from the L.A. Times!”

Under “C,” for Catholics, my contact file began to bulge. On many Sundays I went to Mass twice—once at the cathedral and once at some rebel parish. I am not Catholic, but by Advent I had memorized the responses that worshippers recite each Sunday. I knew when to kneel and when to stand. “Hum a few bars and she fakes it,” said Father Frank Fitzpatrick, a Brockton “good priest” I came to know and admire.

Now a full year has passed. The cardinal is gone, but this story shows no signs of going away, much less slowing down. Almost 500 civil claims are pending against an archdiocese that has threatened bankruptcy to avoid payment. New victims continue to pour forth. Previously confidential church documents—papers long kept locked in secret chancery files—now are entered into court records. After all this time, the shock of reading those records has not worn off, not one bit. Journalistic jadedness or battle fatigue has yet (thank heaven) to rear its weary head.

The sadness never leaves this story. These are, after all, real people. Almost universally they seem less intent on financial restitution (if such is possible) than on striving to assure that no boy or girl ever suffers the way they did. But mixed with the sorrow is the promise of transformation. All over America, Catholics are questioning their hierarchy and calling for reform. Fine, strong priests have emerged to make their profession proud.

In some ways, the clerical abuse scandal has become a journalism textbook. Consider the elements: power, corruption, intrigue, tragedy, sex, betrayal, money—and an institution that dates back 2,000 years. Faith and morality juggle with hundreds of heroes and just as many victims. The villains are despicable. Meanwhile, the proverbial quest for truth and justice—what brought us all into this line of endeavor, after all—is always at the forefront.

All these qualities and characters are crammed onto that freight train that rushed out of the Boston station more than a year ago. One thing is certain: This wild and crazy ride is nowhere close to complete.

Elizabeth Mehren is New England bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times where she has worked for more than 20 years. She is also the author of three books, including “Born Too Soon: The Story of Emily, Our Premature Baby.”