The idea was simple. If the Pentagon was embedding journalists with military units in the invasion of Iraq, why couldn’t it apply the same principle inside the nation’s largest military hospital? This was the essence of the pitch that Tamara Jones, a fellow Washington Post reporter, and I made to the commander at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

The war was seven weeks old when Tamara and I, both feature writers for the Post, decided to team up to report a story about the war wounded being shipped home from Operation Iraqi Freedom). Working at the Post, we had the benefit of geography: Almost all military casualties funnel through either Walter Reed or National Naval Medical Center in nearby Bethesda, Maryland. Our loose idea was “St. Elsewhere” in wartime. We’d locate ourselves inside a military hospital to explore the physical and psychological aftermath of war. We wanted a counterpoint to the ongoing stories and imagery of tanks rolling toward Baghdad and Pentagon officials pointing at maps. It was time for a gut check. The casualties were starting to come home.

In its ambition, the story was a straightforward feature. But to report it required special access. Aside from a few brief interviews, no journalists had been given prolonged access to soldiers at Walter Reed since the war started. To make matters more difficult, Pfc. Jessica Lynch had recently been admitted, and the hospital was in a tighter lockdown than normal. The final hurdle was HIPAA, a new federal patient privacy law that had just taken effect and would seriously limit our ability to even be near patients.

We met with Major General Kevin Kiley at Walter Reed to make our request. We brought clips and offered references. We promised nothing except fairness and sensitivity. Driving home from that meeting, Tamara and I put our chances at 50-50. Why would the government let us write about the realities of war? Working in our favor was the fact that the embedding concept was generally viewed as successful. After two long weeks, we received the green light, with one disappointing caveat: We would be shadowed at all times by either a public affairs officer (PAO) or a judge advocate general (JAG) officer. We agreed. The second blow came on our first day of reporting. President Bush announced that major combat operations in Iraq were over. But what seemed like terrible timing for this story actually turned out to be a haunting theme. Though major combat operations were over, the casualties kept coming.

Embedded at the Hospital

Walter Reed is a 147-acre compound. To have tried to write about the whole hospital would have diluted the potential impact of the material. After a few days of reporting, we decided to locate our entire story on Ward 57, the orthopedic ward where amputees are treated. There is probably no other place in the hospital that reveals with more nakedness the after-tremors of war.

At 5:30 each morning, we began making rounds with doctors. Most of the soldiers had lost a leg to landmines, rocket-propelled grenades, or sniper fire. Some were having additional surgeries for a higher amputation due to infection or to prepare the stump for a prosthetic. Bandages had to be changed daily, often with the help of a morphine injection. These initial few days of reporting involved a lot of quiet observation out of respect for the soldiers’ privacy. While we gave the soldiers plenty of space early on, we hounded the doctors and nurses with numerous questions.

After meeting a dozen soldiers, we narrowed our focus to three, each distinct in personality, rank and resolve. First Lt. John Fernandez was a West Point graduate and newlywed who’d lost both legs in a rocket attack. Pfc. Garth Stewart was a ground-pounder who loved combat and philosophy. Pfc. Danny Roberts was a bookish reservist who had the most trouble dealing with his injury.

As with all reporting—but especially narrative reporting—it was crucial to witness firsthand as much as possible. We had the good fortune, too, of having Post photographer Michael Lutzky work with us. As time went by, the three of us roamed unaccompanied through most of the hospital, unencumbered by the PAO or JAG officer. We had either earned their trust or outlasted their stamina.

In many ways, Walter Reed was like any hospital. There were moments of human suffering, peak drama, and numbing boredom. The main difference was that these patients were linked to each other by the same brutal circumstance. They had crossed the sands of Iraq as whole men and they had come home physically compromised. Now they were all lying under the same fluorescent lights on the fifth floor at Walter Reed, with CNN flickering live from Baghdad. The parallel worlds were always toggling.

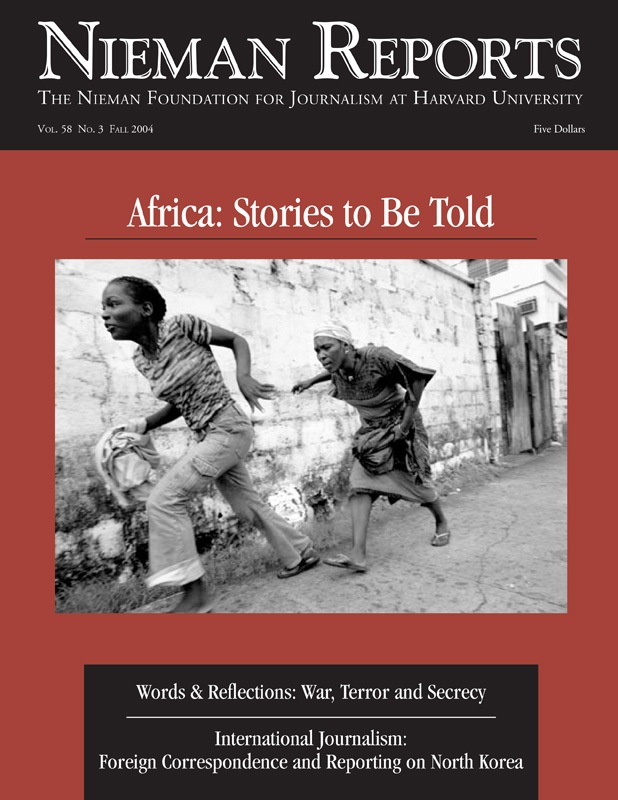

Garth Stewart shows his buddies his new leg after they returned home to Fort Benning from their tour in Iraq. Photo by Michael Lutzky/Courtesy of The Washington Post.

Interweaving Layers of the Story

We expected the soldiers to have some bitterness. We found mostly the opposite—a generation of enlisted professionals grossly inconvenienced by their injury. The army was their vocation, and the American flag was their company logo. They had been trained and went willingly, even eagerly, and these were the consequences. Sometimes we struggled to understand this mindset. Here was Lt. Fernandez, a former lacrosse captain at West Point, who came home from Iraq with bandaged feet but, 12 surgeries later, both legs were amputated. Nurses on Ward 57 broke hospital rules by slipping a cot into Fernandez’s room so that his new wife, Kristi, could sleep next to him. As Fernandez got stronger, he moved from a bed to a wheelchair. He expressed only stoicism. We reminded ourselves that we were witnessing the first phase of a long journey. Maybe anger would come later, maybe it wouldn’t.

During the 15 days we spent at Walter Reed, Tamara and I tried to pierce through the “Band of Brothers” mentality that seemed to inhabit this ward. I now believe many of the soldiers were still in some form of shock. The one place you could see them confronting their new limitations was physical therapy. Some cried. Some yelled in agony. Some just lay on the tables and stared at the ceiling.

We consciously wanted to avoid either extreme of hyper-patriotism or ironic cynicism. But some truths were hard to ignore. The White House talked of a decisive victory in Iraq while the planeloads of wounded kept coming. Every day at Walter Reed, we watched members of Congress and other government officials make the rounds on Ward 57, at times waking soldiers up to shake their hand so that a photograph could be taken. Soldiers combed their hair for Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s visit but it was Jim Mayer, a double-amputee from Vietnam, in whom they really confided. As young as the soldiers were, their radar was acute enough to sniff out frauds and glad-handers. They saved their confidences for other soldiers.

Ward 57 had plenty of humor. One soldier, newly dosed with morphine, asked if any Playboy bunnies were in the house. When Hulk Hogan visited the ward, he looked down at a young private who’d lost his foot to a land mine and growled, “They’ll fix that flat tire and get you runnin’ again.” Such logic from a man with orange skin was much appreciated. The soldiers’ jubilation over the ridiculous was a profound reminder that most of them were just 19 or 20-year-olds.

No soldier was willing to publicly criticize the United States or the decision to go to war. Our reporting took place before the mission became so messy and prolonged and before the various reports on the flawed intelligence that led the United States to invade Iraq. Returning to Ward 57 now might yield a different story.

Publishing the Soldiers’ Stories

After our three soldiers were discharged, we did some follow-up reporting and then spent three weeks writing the story. We struggled to find a unified voice between two writers. We disagreed over what emotional trigger points were important or not. Editor Mary Hadar kept the train on the tracks. Our story ran as a two-day series on the front page of the Post, accompanied by wrenching photos. The Post received a lot of mail. Veterans wrote to say thanks for paying respect to our nation’s warriors. Those who opposed the war wrote similar notes of gratitude. Both “sides” felt that their “truths” had been aired.

A closing note: When our story was published in July 2003, Walter Reed had treated 650 battle casualties from Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). As I write this essay, Walter Reed has just released its weekly bulletin, dated August 30, 2004, with its number of OIF casualties treated: 3,403.

Anne Hull, a 1995 Nieman Fellow, is a national correspondent for The Washington Post.