The process of dissecting the human body during Gross Anatomy class forces medical students to face death, all in the hope of better understanding life. This introductory experience is considered a major transition in the training of physicians. And how medical students emerge from their training sets the tone for the relationships they will form with their patients.

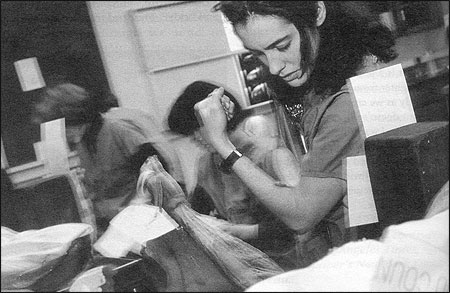

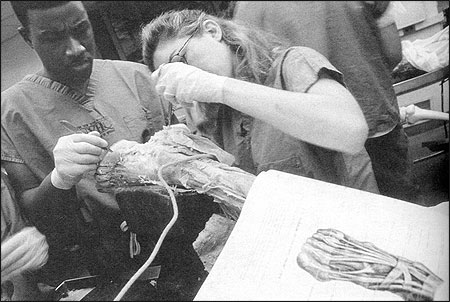

“Anatomy of Anatomy,” a book and traveling exhibition, combines my photographs of a group of first-year medical students during their anatomy class with excerpts from journals they kept. During the past decade, I have focused my camera on issues of health and social welfare, observing the delivery of health care from the patient side. Over time, I became curious about the unique skill-set required of physicians, as well as the intensity of their training.

This led me to Cornell University’s Weill Medical College in the spring of 1998. There I sought out a small group of medical students willing to collaborate with me on a project that would document their anatomy course. We worked in the basement lab, at the library and in dorms, recording the struggle of these doctors-to-be as they learned the innermost workings of the human body. All of this was made possible because of the generosity of individuals who, in death, donated their bodies to medical education.

We discovered that the dead can teach us in many ways. With honesty and openness, these students wrote about their experiences and their relationships to their cadavers, or as one student wrote, her “own really live dead body.” The students’ words help provide “Anatomy of Anatomy” with a clear narrative framework.

As these words and images have traveled to 13 exhibition sites within the medical education arena, I’ve worked closely with educators and students, organizing panel discussions to explore the complex journey of moving from patient, to medical student, to physician.

Meryl Levin is a social documentary photographer based in New York City. “Anatomy of Anatomy” and its traveling exhibition were made possible by the Open Society Institute’s “Project on Death in America.” More information about the book and exhibition can be found at www.ThirdRailPress.org.

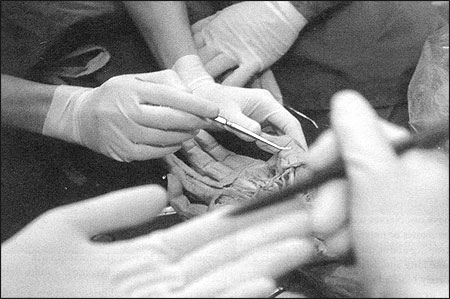

I have finished my dissection of the wrist and hand. It is 3 p.m., and I have to pick up my daughter from school. I hold her hand tightly as we cross the street. She notices, but doesn’t say anything. Her hand is soft and warm despite the January cold. This is what life feels like, I say to myself. I have learned something about the human touch. I will never hold someone’s hand the same old, ignorant way again. —Rajiv

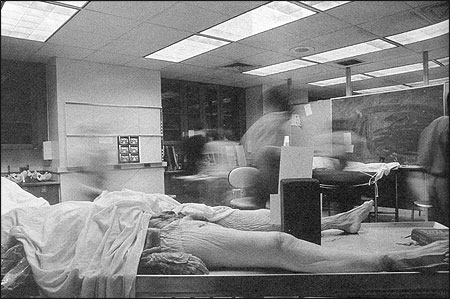

It happened so fast. One minute I was running to class finishing my cup of coffee, the next minute I’m in front of a chalkboard, watching the teaching assistant explain the subject area to be covered today. No different from any other day—a teacher, a bunch of students gathered around. But lying on the metal table right next to me was a real, live, dead body. Well, not really. But a dead body ….

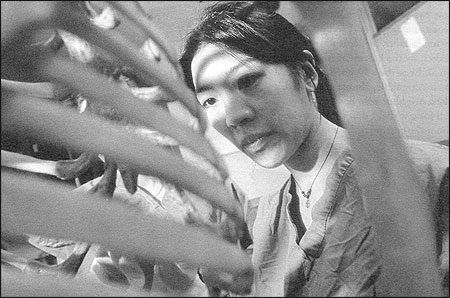

From the minute I laid eyes on my own anatomy cadaver, I looked for clues that would help me piece together her life. I don’t know why that was important to me. I wondered why she decided to donate her body to science, and then I wondered if I could make that same decision. Did she know what was in store for her when she signed the consent form?

As I looked around at all the blades and scissors and other sharp metal utensils strewn around the room, I wondered if I knew what was in store for the both of us. —Hilary

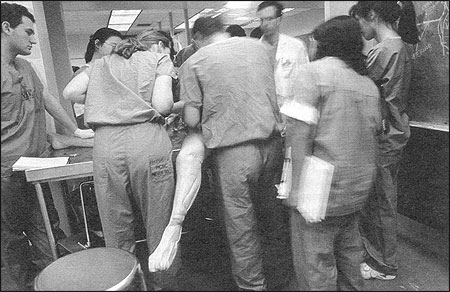

Thirteen outstretched arms greet me. The bodies on which we have worked for the last two weeks are all covered under a white sheet except for the neck, the shoulder, and the arm.…

Professor Weber explains how the [test] is going to work. We will get a minute and a half to view whatever needs to be identified and then move on to the rest area next to the body to write our answers.

A bell rings, and it starts. Fifty-two living circle around the 13 dead. We bend down over the little tag, trace the thin black string that emanates from it, stare for a minute and a half at the body part tied to the string, and then move on. Nerves on edge try to recall the names of nerves that have stopped stressing about the trite and the mundane long ago. Most of us have completely blocked out the body attached to the part in question ….

In this macabre game of musical chairs, with music replaced by timed silence punctuated by a ringing bell, I make my way to my cadaver. Even though I can only see a part of his forearm, I have no trouble discerning that he is mine …. —Rajiv

The room was both a morgue and a classroom. At the beginning of anatomy, I had a hard time separating the idea of a morgue from my mind whenever I entered the room. The cadavers were not yet classroom learning tools, but only dead bodies. This caused me to view my own body in a different light. In a way, I was repulsed. I looked at my naked body in the shower and thought of hers. Though her aged lifeless body did not hold a close resemblance to my own, I couldn’t help but think that the life-giving blood that coursed through my vessels was transient and would some day stop—and that I would become like her. —Hilary

In preparation for today’s first lab of the lower limb, I felt nothing. It may be that after the grit and awe of handling his heart and lungs, the viscera of his abdomen and his urogenital organs, my cadaver’s anterior thigh was not very inspiring. I think I felt that there were no more secrets left to move me. I was wrong. It was the most profound day yet.

After seeing the prosection, I knew what I wanted to work on. I felt a powerful need to dissect out his right greater saphenous vein. I took my time and slowly cleaned it of all of its attachments to the surrounding tissue. I felt obliged to dissect it out beautifully, in homage to my cadaver, “Stanley.” The task was soothing. When I was through, it glistened perfectly, a milky blue from the upper thigh all the way down to the medial knee. I backed away from the table and started to tremble. I thought of my father, who is still alive after two cardiac bypass surgeries. His own saphenous veins from both legs are miraculously part of his damaged heart’s circulation. They are his vessels of life and are the reason he saw me graduate from high school, from college, get married, and have two children.

Today, I became aware of how close I was to losing my father and how miraculous it is that he is still alive. For this, in addition to all that I’ve had the great privilege to learn, I am most grateful to Stanley. —Michael

The power of habit is incredible. It is now two-and-a-half months since we began anatomy, and I feel unstartled by my cadaver, by all of the dead bodies, by the basement room, and the ritual. Even the oily smell which coats me is acceptable, almost unnoticed, like a neighbor who has lived down the hall for a while. I don’t think twice about the cutting or having lunch afterward. I no longer draw silent comparisons between my cadaver’s subcutaneous fascia and my son’s unblemished face. Gross Anatomy has become one of the routine workings of my life and, by some sad equation, I am now wondering less about my cadaver’s life, his routines, his visions, his loves, and his thought process that ultimately brought him to the anatomy lab. —Michael

Strangely, my most emotional responses to anatomy have been in retrospect. While reflecting on the course, I’ve allowed my emotional side to be involved in a way that I could not do previously. During the course, it was like a survival mechanism took over: Repress all sentiment, the thing in front of you is, indeed, a thing, not a person, not even something that once was a person. But I think about the cadaver now not as a thing, not as “my cadaver,” but as Alice.

We, the six people in my group, always referred to her as “Alice.” And we were proud of her. She was a good cadaver. She did not smell. Her organs had not decayed. Somehow, I think I believed that this preservation phenomenon was attributable to Alice herself. …

The dissection was a collaboration between Alice and me, between Alice and the six of us who had been assigned to her. —Katie