In 2009, Grossman was part of a Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting team that created “Heat of the Moment,” a multimedia project on Climate Change. Listen to his hour-long radio piece here, and view additional reporting on climate change here. Researchers have known for more than a century that carbon dioxide released into the air when coal, oil and other fossil fuels are burned could trap extra heat in the atmosphere, causing the planet to heat up. But it is only in the past decade or two that scientists have accumulated convincing evidence that the planet actually is getting warmer and that humans are a (if not the) major cause. Today, no credible scientist questions that humans are warming the earth. Far less is known about what warmer temperatures will mean for earth’s inhabitants, human and otherwise. I have devoted the last several years to accompanying scientists to some of the research sites where they are studying the impacts of climate change. Much of this research takes place near earth’s poles, since the Arctic and Antarctic are heating up faster than anywhere else. Felicitously, such distant, inaccessible places have a grip on the popular imagination that I believe attracts greater attention to my writing than would reporting from less exotic sites.

Mary Manning in her garden. Photo by Daniel Grossman.

When Flowers Bloom

In 1965, Mary Manning, a schoolteacher from Norwich, England, noticed that daffodils in her backyard were blooming well before Easter. Her mother, this teacher then realized, used to think it a rare blessing if these harbingers of spring blossomed in time to decorate the church for the Easter service. Ever since that year, Manning has been recording the first blossoming dates of aconites, crocuses, snowdrops and many other flowers in her garden, as well as the presence of migratory birds. She says she hasn’t failed to observe her garden for a single day. “It’s not the jolliest thing to do,” she says about making observations on frosty December mornings, “but its got to be done.”

Climate researchers say such extended observations of the timing of plant and animal behavior (a kind of study known as phenology) help reveal how global warming is affecting ecosystems. Few scientists collect such long-term data, especially since the 19th century, when experimental research began to overtake observational studies. So contributions from amateurs like Mary Manning are welcome. Tim Sparks, a researcher at Great Britain’s Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, has collected records from about 100 such “closet phenologists.” In one paper he published using Manning’s 40-year-long nature journal, he showed that five plants were flowering more than five days earlier per decade. Primrose, the record holder, flowered 10 weeks earlier during the 1990’s than it did between 1965 and 1980. Sparks is worried because if different members of plant and animal communities that interact with each other change at different rates, ecosystems could literally come undone. “The communities, the types of woodlands,” he says, describing the impact he expects to result from these changes in timing, “will not be similar to those that we have now.”

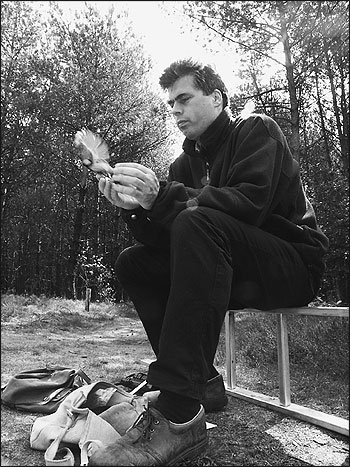

Marcel Visser with the bird he studies. Photo by Daniel Grossman.

When Ecosystems Decouple

Marcel Visser of The Netherlands Institute of Ecology oversees a 50-year-long study of a bird known as the great tit. Visser’s research, in the De Hoge Veluwe National Park in the middle of the Netherlands, is one of the world’s few studies to examine how a cascade of changes caused by global warming can ripple through an ecosystem.

In early spring, breeding tits feed voracious hatchlings highly nutritious caterpillars. The caterpillars, in turn, nourish themselves by feeding on tender, newly opened leaves of oak trees. Twenty years ago these three organisms—the oak trees, the caterpillars, and the tits—passed the phases of their life cycles in synchrony like the choreographic feats of ballet dancers who twist and leap together in time to a rhythmic beat. But today, like performers dancing to slightly different rhythms, the members of this short food chain are becoming, as Visser puts it, “decoupled.” It appears that each of the three organisms is responding differently to global warming. Spring temperatures in De Hoge Veluwe Park have increased by about two degrees Celsius in the past 20 years. The birds’ behavior has remained virtually unchanged: They lay their eggs almost exactly when they did in 1985. The caterpillars, in contrast, seem to have responded to increased temperatures by hatching earlier. Today the peak availability of caterpillar flesh occurs about two weeks earlier than in 1985. As a result, by the time the tits hatch, their food is already on the wane. Now only the earliest chick gets the worm.

Oak trees are also waking up from the winter earlier in the spring. But, in contrast to the caterpillars, the leaves of oaks open only 10 days earlier than they did 20 years ago. So the caterpillars, which used to synchronize their lives with the arrival of the oak leaves, now have to wait for food for an average of about five days extra. Apart from small declines in caterpillar numbers and changes in tit-chick health, Visser has yet to show that the ecosystem is actually suffering from the changes. However, in a system where “timing is everything,” he says “it only a matter of time before we see the population come down.”

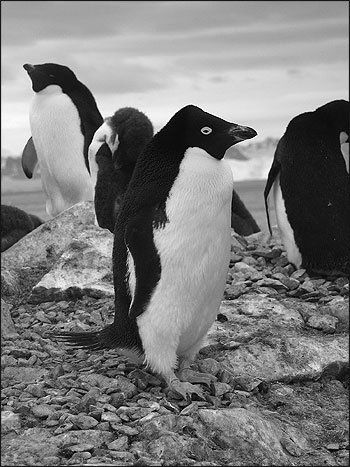

Adelie penguins in the Antarctic. Photo by Daniel Grossman.

When Penguins Breed

Bill Fraser, an ecologist from Montana, says that Adelie penguins near America’s Palmer Station research base on the Antarctic Peninsula are being wiped out by global warming. In the approximately 30 years since Fraser first visited Palmer Station, the number of Adelies there has dropped by about 70 percent. Winter temperatures in the Antarctic Peninsula have warmed a remarkable six degrees Celsius in the past 50 years. As a result, sea ice, which covers the ocean for hundreds of miles for much of the year with an impermeable cover, is less extensive than it used to be. That means more water vapor can evaporate into the atmosphere and return to earth as additional rain or snow. And so, counterintuitively, global warming has increased snowfall along the Antarctic Peninsula, which Fraser says is reducing breeding success of these penguins.

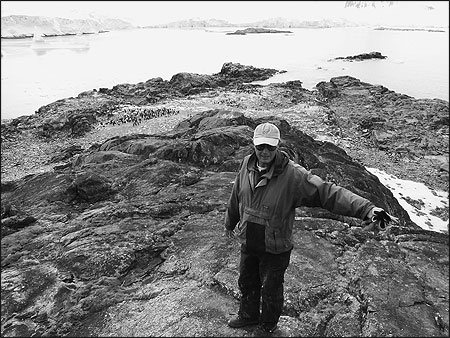

Fraser shows how the spatial pattern of Adelie declines provided him with essential clues. The scientist discovered that Adelie colonies at the base of south-facing slopes had been hit worst. In the photograph below, he points to one such hillside, where the prevailing winds of winter storms deposit snowdrifts. In the southern hemisphere, southern slopes get less sunlight and thus are the last to become snow-free in the spring and summer. Increased snowfall has left these areas snow-covered much later than in the past (a small drift is seen just behind Fraser’s outstretched hand in the middle of the Antarctic summer). Adelies cannot breed successfully until their gravel nest sites are snow-free. Sometimes impatient birds will try to nest on top of the snow of late-melting nesting sites. However, their nests flood and their eggs are destroyed when the sites finally clear. When Fraser began his surveys, the entire flat base of this island was covered with Adelies. Now all that remains of the once-teaming colony is the handful of birds seen in the background to the left of Fraser’s head.

Fraser says he expects the colonies around Palmer Station to be completely gone within a decade. The researcher, who has spent his entire professional career studying the decline of these birds, mourns their disappearance. Nonetheless he says he is gratified at the thought that their loss might, by alerting the world to the threat of global warming, be a gain for animals elsewhere. “The Adelies,” he says, “are an honest barometer of global changes.”

Melting sea ice near the Antartic Peninsula.

Bill Fraser points to a snowy hillside. Photos by Daniel Grossman.

Researchers believe that reduced sea ice caused by global warming could create problems for polar bears who normally live and hunt on pack ice. Photo by Daniel Grossman.

When Drift Ice Melts

On the fringes of North America, Asia and Europe, ringing the top of the world like the collar of a hand-knit sweater, is a fragile ecosystem known as the high Arctic. Conditions there are hostile, possibly at the limit of what complex organisms on earth can endure. For months at a time the sun never rises. Winter temperatures commonly drop to tens of degrees below zero Celsius. And so little precipitation falls each year that this polar region is considered a desert. Nonetheless the high Arctic is home to a diverse collection of birds and mammals, including the polar bear, arctic fox, muskox, lemming, snowy owl, plover and falcon.

Zackenberg Station, located in the high Arctic of northeast Greenland, is the second most northerly research base in the world. It is the only place in Greenland, and one of the few on earth, where very long-term observations are made of a broad range of attributes of the environment, including plant and animal life and climate, river, soil and snow conditions. The station, operated by Denmark since 1995, was founded on the principle that in order to truly understand the impact of climate change on earth’s plants and animals, data must be collected for 50 years or more.

Hans Meltofte, Zackenberg’s founder, says it is too early to draw any conclusions about the impact of climate change on the station’s high-Arctic habitat. However, he says that in the decade since the base opened, researchers there have made discoveries that raise serious concerns. For instance, climatologists predict that drift ice, the rivers of densely packed Arctic icebergs that steam down Greenland’s coasts, will become less extensive as temperatures rise. This ice is like a lid on the sea, reducing evaporation and keeping snowfall low. Less ice could thus mean more snow, and more snow, in turn, could mean birds that require bare ground after the winter’s snows have melted to nest will have to wait until later in the season to lay eggs. Their chicks would have less time to mature before migrating, threatening their survival. Alternatively, if breeding birds try to stay on schedule by nesting in less optimal areas, eggs could be more vulnerable to predators like foxes. Warmer temperatures could also cause ice crusts to form on snow, making it difficult for the muskox to forage. In other parts of the world, ecosystems might be able to respond to warming by moving north. But at the top of the world, the high Arctic has nowhere to go but the Arctic Ocean. Asked if the plants and animals here could be exterminated, Meltofte pauses then says, “It is a hard word to say for an ecologist. But it is not unlikely.”

Danish scientists are trying to discover how warmer conditions, which are expected to cause more snow accumulation, will affect vegetation like the cotton grass and wildlife that depend on it.

Hans Meltofte works in the high Arctic of northeast Greenland. Photos by Daniel Grossman.

Daniel Grossman is a radio producer and print and Web journalist whose reporting focuses on science and the environment. His radio documentary, “The Penguin Barometer,” won the 2004 Media Award for Broadcast Journalism from the American Institute of Biological Sciences and an award from the Society for Environmental Journalists for outstanding in-depth radio reporting. His Web site on Madagascar won the 2005 Science Journalism Award for online media from the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Grossman’s work can be seen and heard at www.wbur.org.