In 2001, the Star-Gazette in Elmira, New York, embarked on publication of a yearlong project examining how cancer affects our community and its residents. The idea for this project emerged out of an event that happened in early 2000, when a small but vocal group of parents sent a letter to the Elmira school board to demand an investigation into a seemingly high number of cancer cases among current and former students and faculty at Southside High School.

Southside High, built in 1978, is on a site that was home to industries since the late 1880’s. The parents’ letter told of 13 cancer cases among students since 1997—including six students who were then at the 1,100-student school. By mid-summer, the number of reported cases had risen to 40.

These parents sent a similar letter to state and local health departments, sparking a New York State Department of Health investigation. But as the probe went on, few clear answers were being found, and the community’s frustration was growing. As we reported on this investigation, members of our staff were learning more about cancer. By August 2000, with stories about the school cancer probe appearing nearly every week but with no clear link established, we decided to launch a project examining the impact cancer was having on families and on our community and, in turn, become a vehicle for giving residents more information about how this disease can be caused.

Why We Did This Cancer Project

Former Managing Editor Mark Baldwin wrote in our grant application to the Pew Center for Civic Journalism, “The Star-Gazette is embarking on a yearlong public journalism project aimed at encouraging residents of our community to take control of their own health by reducing their risk of cancer.” While the state couldn’t prove a link between cancer and the school, we felt we could at least arm our readers with information vital to their health. We approached our Elmira TV partner, WETM Channel 18, an NBC affiliate, and the area PBS TV and radio affiliate, WSKG Public Broadcasting in Binghamton, New York. Both wanted to join us in working on this project.

Our approach would bring a bit of a twist to the traditional civic journalism model. In this case, rather than setting out with an expectation that we could help people to stop or cure cancer, we’d simply inform them about steps they could take to possibly prevent cancer. The goal for us became educating the public on the various kinds and known causes of cancer and looking at how various types are treated, including the cost and consequences of this disease.

As we began, we had several decisions to make:

- Determining how to involve the local cancer community in this project.

- Learning how much people in our community already knew about cancer and its causes.

- Deciding how we’d tell the stories we found in the community.

- Figuring out where to begin our reporting.

The Star-Gazette is a 29,000-circulation paper with a staff of about a dozen reporters who cover small municipalities, schools, cops and businesses. We don’t have medical writers or science writers, though in the process of reporting these stories, many of our reporters became quite knowledgeable about this disease. And even though we had done civic journalism before, we’d never taken on a project of this magnitude.

How We Reported the Stories

On September 21, 2000, staff from the Star-Gazette held an informal dinner meeting at the American Cancer Society’s office in Elmira. A group of reporters, editors and producers filled our plates with fresh fruits and salads, and we sat among cancer patients, nurses, physicians and cancer educators. During the next two hours, we listened and took notes, and by the time our get-together ended, we’d found plenty of story ideas. Included among them were: defining cancer, coping with cancer, paying the bills, smoking and cancer, diet and cancer, environmental concerns, and educating children. These ideas became the spine of our yearlong project.

Every month we focused on one topic, such as cancer and the environment that we featured in May. Our main story that month was about brownfield sites, properties where use or development might be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant or contaminant. We reported on former industrial sites in our community and their legacies. On two inside pages, readers found an interview with Jan Schlichtmann, the lawyer whose legal work in the Woburn, Massachusetts case was featured in the book and film, “A Civil Action.” He talked about how Hollywood has glamorized the complexities of environmental cancer cases with movies such as “Erin Brockovich.” Another sidebar focused on environmental laws that a new steel fabricating company moving into our area needed to meet. Readers were also given shorter stories and locations on a map of the United States of communities—including Elmira—where people are trying to or have established a link between industry and cancer or disease.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Alcoholism: Its Origins, Consequences and Costs" (Spring 2003)

- Eric NewhouseThe group we’d met with in September also became our advisory board. Often, reporters and editors called them to help find local sources or to clarify medical terminology. And, when we needed journalism advice, the Star-Gazette newsroom met with Eric Newhouse, projects editor for the Great Falls (Mont.) Tribune, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 2000 for a project on alcoholism. Advisory board members also helped us establish what I’ll call the “furniture” of our monthly print packages. Each month there was a Question & Answer section between a reader and expert (in May, the question was “How much cancer is caused by environmental factors?”), a list of area support groups, and a spotlight on a respected cancer-related Web site, such as the American Cancer Society, Harvard University’s cancer risk calculator, and the New York State Department of Health. These features provided a steady stream of information that we were able to bring to the community as well as resources where they could search for more.

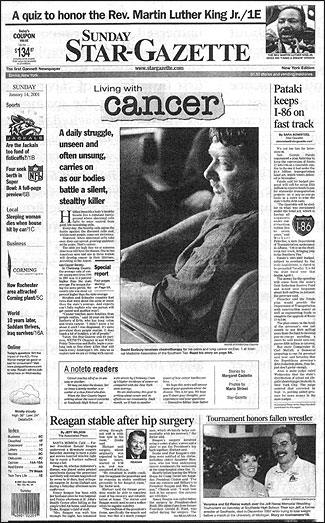

By late 2000—with assistance from the Pew grant—many on our staff were immersed in cancer reporting. An editor, reporter, photographer, designer and graphic artist were working on the first installment of “Living With Cancer.” Following the example of how Newhouse approached his coverage of alcoholism at the Great Falls Tribune, our opening day installment would profile a day-in-the-life of cancer in our community. We also worked with Zogby International, a polling firm based in Utica, New York, to develop questions for a community-wide telephone survey on cancer.

Reporters and editors were surprised at the outpouring of community support that came as soon as the project began. During the telephone survey, nearly everyone contacted agreed to allow the media to get in touch with them again for future articles. Local physicians, who are usually hard to reach, returned phone calls and offered to make themselves available for interviews for future articles. Support groups began calling to ask how they could contribute to our reporting; when we focused attention on ways of coping with cancer, hearing from support group members was invaluable. In response to this outpouring of interest from the community, the Star-Gazette created a “source form” for groups to distribute to their members.

Lessons Learned

As I look back on this reporting project, there are lessons we learned that would be of value for news organizations considering such a project:

- Find and cultivate community support. We couldn’t have attempted this project without full community support. We found this support as soon as we let our readers and viewers know—through an interview broadcast on Channel 18— that the project was beginning. And the help offered by the local and regional offices of the American Cancer Society proved to be invaluable: They gave us permission to print cancer quizzes from the organization’s Web site and put us in contact with experts for the monthly Q. and A.’s. Any fears we had about finding sources disappeared quickly. With the support of the area medical community, our reporters were given access to two cancer treatment centers. A visit by Star-Gazette reporter Margaret Costello and staff photographer Maria Strinni provided some of the series’ most poignant words and images. We knew we needed to tell about cancer through the voices of area people. These early experiences of our reporter and photographer solidified that approach. During the year, we revisited the people we originally profiled and updated their conditions. We cheered with one patient as he was cleared of cancer and mourned when he died a week after a doctor told him the cancer had returned. By the end of the series, three cancer patients who were part of the series—including one who served on our advisory board—had died. A fourth source died in early 2002.

- Show your hand. The community can help tell a story if you let them know what story it is you are trying to tell.

- Be willing to adapt story selection. When we started the project, we knew which stories we intended to do and when. We didn’t share the story order with the public, but we did share it with our media partners and advisory board. Members of the board advised us to swap the dates of two installments so that they would coincide with tobacco awareness month and skin cancer prevention screenings that were scheduled.

- If your news organization is going to create an advisory board, keep them in the loop and listen to them.

- Schedule a mid-month run date. Don’t plan on running a monthly package on the last weekend of the month; other news might bump it off your front page.

- Get each installment done early. Relying on advice from Newhouse, we set early deadlines and stuck to them. Stories, photos and graphics were due early to allow for good editing; designers got the packages on time to ensure inspired design. As the main editor on the project, I edited story drafts at my kitchen table and took packages with me on vacations. Often I was in the office on quiet Sunday mornings to read stories and write cut lines. This extra work paid off, too, when editors and reporters didn’t have to scramble to finish their work on this project when a breaking story demanded their full attention. And, with a small staff, retaining this kind of flexibility is essential. In February 2001, when a student entered Southside High School—the same high school that started the project— armed with guns and bombs, we were able to give that story its full coverage even though it occurred four days before the second installment of the cancer project was scheduled to appear. And in September 2001, with our cancer project installment scheduled to run September 16th, it was fully edited by Sunday, September 9th. After the terrorist attacks on September 11th, our paper stayed with reporting on the terrorism story and the cancer project publication date was moved to September 23rd.

- Create a concrete plan with partnering news organizations. The most complex part of this project was ensuring that each news organization found ways to fully participate. The newspaper took the lead role in shaping and reporting the project, but several times during the year “Living with Cancer” was featured on the NBC affiliate’s local Sunday news show. This series was also the subject of news and call-in shows on the local PBS affiliate; in one instance, a local PBS producer wrote a first-person article about his colonoscopy, which was also featured on a locally produced PBS TV show. The Star-Gazette and Channel 18, the NBC affiliate, each promoted the series in advertisements, articles and promotions. The local PBS affiliate directed viewers from its Web site to the newspaper’s site for more on the series. In retrospect, this partnership could have been stronger. The newspaper was immersed in the project while the other news organizations were on the outside, with little direct involvement in shaping the content of the story. To improve this process, better plans need to be drawn up at the outset. To do this, one person at each news organization should be put in charge of securing commitments about how much each will contribute to the project. Then, as the work is ready for publication or broadcast, these people work to find ways for each entity to draw attention to the combined work.

- Think about the future. If we had to do this all over again, we would have included in our initial grant application a request for funds for a follow-up community survey. Results from it could have told us if and how our reporting efforts influenced members of the community. Also, because reporter turnover is high at small-market newspapers, it is important to develop expertise among a mix of reporters, both new and veteran, as a way of ensuring that the stories will all be told with the same depth, detail and care.

“Living with Cancer” provided our readers and viewers with a compelling report about cancer. By reading it, they could explore in very personal ways how their neighbors were coping with the disease and learn about resources to lessen the chances they would have to deal with cancer. But there are still many families in our community dealing with cancer’s unknown origins.

The cancer investigation at Southside High School that instigated our project has yet to conclude. Last fall the Star-Gazette reported that the school district’s survey of high school alumni wasn’t complete, and no deadline for its completion had been set. The state health department reported that tests of soil around the school showed it was safe. But further investigation efforts were diverted to handle the aftermath of September 11th. We continue to follow the story, but news has slowed to a trickle after three years.

And a little more than a year after “Living With Cancer” ended, we continue to give Page One presence to news about cancer discoveries. However, we tend to be more probing and critical in our reporting about these medical studies because of what reporters and editors learned in doing this series. The Star-Gazette plans a follow-up story this summer in which we hope to learn through our community sources if and how our series affected how people care for their health.

Weathered articles reminding people how to eat a more healthy diet hang on residents’ refrigerators. We know that some people underwent cancer screenings—such as having a colonoscopy—after reading newspaper articles. Even now, 15 months after the project was put to bed, Internet surfers still come across the package on the Star-Gazette Web site and send us e-mail. We can’t be certain of the long-term effects of our effort, but we can be certain we touched lives.

Lois Wilson is deputy metro editor at the Star-Gazette, in Elmira, New York. Prior to joining the Star-Gazette as an editor, she was a reporter at the Palladium-Item in Richmond, Indiana from 1991-1997.