“Beyond the Moment: Irish Photojournalism in Our Time” is the title of a fine slab of a book recently published by the Press Photographers Association of Ireland. This is Ireland as observed by the press photographers who live and work there: the insider’s eye on a country that has changed more times during the past 17 years recorded in this book than the mercurial weather it is famous for.

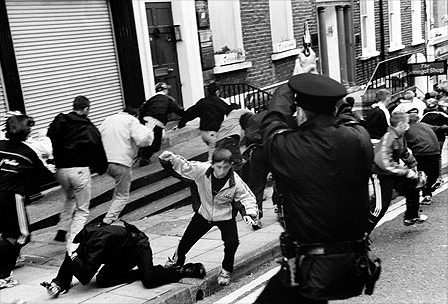

“Beyond the Moment,” introduced by Booker Prize-winning novelist John Banville, is an unsentimental, thought provoking, and revealing examination of the big public moments and the smaller, quieter moments that make up the texture of daily life in Ireland. There are images from political events that made international headlines, such as rioting on the streets of Northern Ireland—and Dublin—both before and after the Good Friday agreement of 1998. But in contrast there are also many glimpses of the more esoteric ways in which the business of politics is domestically conducted. Irish Times photographer Frank Miller’s portrait of the returning officer in a small boat with a ballot box, sheltering under a cloth from the rain while returning with two votes from one of the offshore islands that traditionally ballot some days before elections, is a striking reminder of the truism that all politics are local.

You won’t find pictures of Ireland’s famously quaint, picturesque pubs in “Beyond the Moment,” but you will find gritty, unflinching images of the ever-present role that alcohol continues to play in Irish life. Such as in Kenneth O’Halloran’s important series about the aftermath of a night out, which include a depiction of a dazed-looking woman dressed as a fairy trying to flag a taxi down with a magic wand at 4 a.m. and other images of people gathered like secular tableaux round the prone figures of friends too drunk to remain standing. There are images of familiar Catholic traditions, such as the annual pilgrimage of climbing the holy mountain of Croagh Patrick. But there are also images that show how Ireland is changing, as its immigrant population finally rises, in photographs of a funeral at a Dublin mosque and the baptism of a member of the Eternal Sacred Order of Cherubim and Seraphim Church Noah’s Ark in a swimming pool in the west of Ireland. And there is the irony of a black immigrant, covered in blood, attacked while attending the first-ever antiracism rally in Dublin, which his assault in the preceding days had prompted. All these images tell stories, fragments of the larger narrative that has been going on through the years that saw the Celtic Tiger live and die.

The crazed property overdevelopment that is now hanging like an albatross around the neck of Ireland’s economy is recorded here, too. A mound of mud in County Kildare with a sign that advertises show homes on view optimistically marks the site of a planned new housing development in 2006—perhaps the most relevant statement about the current state of the property market.

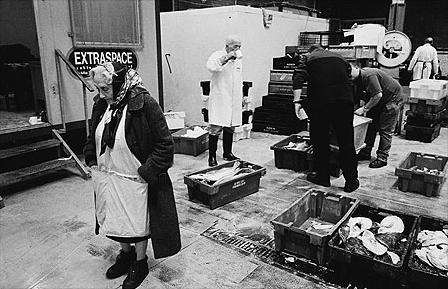

Sometimes, the date on the photograph seems extraordinarily at odds with the subject, such as Lar Boland’s picture of an exhausted-looking elderly woman, a study of work that is reminiscent of the 1950’s, taken at the Dublin Fish Market in 2005, which closed that year. This is real Ireland. So is Mark Condren’s compelling bird’s-eye view, biographical picture of the chaotically bleak one-room flat occupied by a County Leitrim bachelor, also taken in 2005. So also is the image of a backyard in County Clare, taken in 2002, where two undertaker brothers prepare a coffin for a funeral while the wife of one of them calmly hangs the family washing on a line over the coffin.

Thankfully, no matter how grim the times are—and in 2009 they are as bad as the black days of recession in the 1980’s were—Ireland has always been able to laugh at itself and see the humor that flashes through more serious situations. And so we see Gerry Adams spontaneously throwing a snowball in Matt Kavanagh’s campaign trail picture and Colin Keegan’s eye-catching portrait of former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, as he appears to float surreally and saintlike above the freak flood waters that poured down on his Dublin constituency in 2002.

For me, the real spirit of Ireland is in Joe O’Shaughnessy’s picture of the woman he found sunbathing on a Galway wall. Represented only by her bare knees and abandoned shoes as she lies back unseen from the camera, this is perhaps the most entertaining picture in the book, capturing a philosophy all Irish people will recognize—when the sun shines, stop everything and live in the moment.

Rosita Boland, a 2009 Nieman Fellow, is a features writer with the Irish Times. “Beyond the Moment, Irish Photojournalism in Our Time,” is edited by Colin Jacobson and published by the Press Photographers Association of Ireland in association with that organization’s AIB Photojournalism Awards. Images from the book can be seen at www.ppai.ie/books.