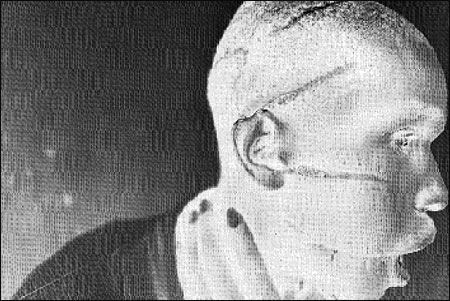

A Hutu man who did not support the genocide had been imprisoned in a concentration camp, starved, and attacked with machetes. He managed to survive, and after he was freed was placed in the care of the Red Cross. © James Nachtwey/courtesy Phaidon Press.

“There’s a tension between the objective and subjective in reporting. The feelings you have about what you’ve witnessed—anger, disbelief, compassion—those feelings have to be channeled into your photographs. In front of you are objective facts, but photography is a process of selection: how you perceive the light, what you leave out of the frame. These are all factors in creating a certain effect, and I want to create an effect.” — Nachtwey

“I deal with raw evidence, but I want it to have a sense of deeper emotion. Compassion is the uniting force in this book—compassion in the face of injustice, struggle, tragedy and loss.” — Nachtwey

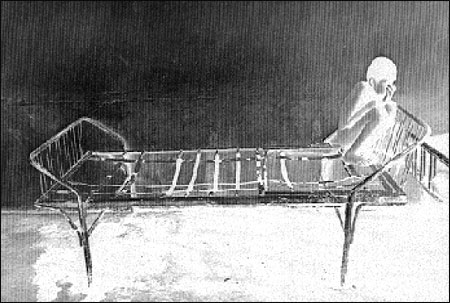

Romania, 1990. Inside an institution for “incurables.” © James Nachtwey/courtesy Phaidon Press.

“If I cave in, if I fold up because of the emotional obstacles that are in front of me, I’m useless. There is no point in me being there in the first place. And I think if you go to places where people are experiencing these kinds of tragedies with a camera, you have a responsibility. The value of it is to make an appeal to the rest of the world, to create an impetus where change is possible through public opinion. Public opinion is created through awareness. My job is to help create the awareness.” — Nachtwey

“I don’t want to let people off the hook. I don’t want to make these pictures easy to look at. I want to ruin people’s day if I have to. I want to stop them in their tracks and make them think of people beyond themselves.” — Nachtwey