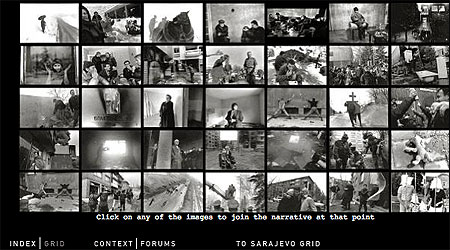

Photographs create a navigational grid for the Bosnia project.

Context. Layered information. Voice. Movement. Transparency. Photographer as “author.” Subject as “storyteller.” Image as “instigator.”

Words and phrases that even a few years ago were not used to describe the practice of photojournalism surface today with hesitant certainty. Where the digital road is leading those whose livelihood relies on the visual portrayal of our contemporary lives might not be entirely clear. By adapting to technology in shooting their images and in how they publish and distribute their work, photojournalists are constructing roads that are already taking them in new and sometimes unanticipated directions.

It was more than half a century ago when an American publisher placed an abstract painting by Matisse and an unforgettable phrase onto the cover of a portfolio of 126 photographs taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson. That title—“The Decisive Moment”—defined for the last half of the 20th century what photographers set out to capture. That the book’s French edition carried the words “Images a la Sauvette,” which translated is closer to “images on the run,” didn’t seem to matter nor did the different treatment of images and words; his French edition had captions, while the U.S. one did not.

A few years later, in an interview with The Washington Post, Cartier-Bresson observed: “There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative. Oop! The moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever.”

Today high-definition video cameras can create high-resolution images at a rate of 30 photographs a second, eliminating the need to know when to click the camera. With audio in the mix, the decisive moment yields to the visual voice. An image, still or moving when shot, will inevitably appear on a screen accompanied by the voices of the photographer and subject telling the story. This task was once left for a single immovable image to do.

In this Spring 2010 issue of Nieman Reports, photojournalists explore the new pathways that their images travel in the digital age. Those at photo agencies share ideas about online business strategies designed to give photographers the time and resources their work requires. Few photojournalists receive what David Burnett refers to as “magic phone calls” from photo editors, the ones sending them with pay and expenses on lengthy assignments to distant lands. So the need to find new revenue streams in a marketplace saturated with images rests heavy on their minds.

Photojournalism’s destination and audience, once pre-ordained by the news organizations that paid the cost of doing business, are now in flux. Digital possibilities are limitless, but what is now required of photojournalists are an entrepreneurial mindset and a facility with digital tools.

On the Web, photographs now act as gateways to information and context, to stories told by participants and conversations held by viewers. Illustrative of this are two examples, separated by 10 years. One was created in 1996 as a portrayal of the Bosnian conflict, at a time before most journalists considered the Internet as being about much more than e-mail; the other, published more recently, provides a glimpse at the Web’s potential as subjects in photographs come to life through flipbook-style animation.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

“Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace,” is archived at www.pixelpress.org, a Web site examining possibilities in digital media, directed by Fred Ritchin. Read his case history of this Bosnia project »In “Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace,” an early Web photojournalism project by The New York Times, Gilles Peress’s photographs serve as links guiding viewers along a narrative trail of their choosing to background material about Bosnia and into discussion forums. Primitive by today’s multimedia standards, this project was prescient in providing context with a click and in recognizing the expanded role of photographer as author.

Today photojournalists constantly consider which form and what venue will work best for optimum engagement with an audience. To display an uplifting visual story of daily life in Iraqi Kurdistan, photojournalist Ed Kashi partnered with MediaStorm to weave thousands of his photographs into a flipbook-style digital animation. The result is an emotional journey told through photographs that gradually change to simulate motion, as music paces the visual ride. An index of images on the site leads viewers to captioned photographs for deeper context.

Multimedia. Motion. Music. Maximizing impact. Measuring influence. Even words like “meta-photograph”—seeing the image as a digital entryway to revealing layers of content and context—sneak into the photojournalist’s vocabulary today. In this issue, photojournalists write about pushing through the digital disruption to find inventive uses of digital media—ways they hope will pay.