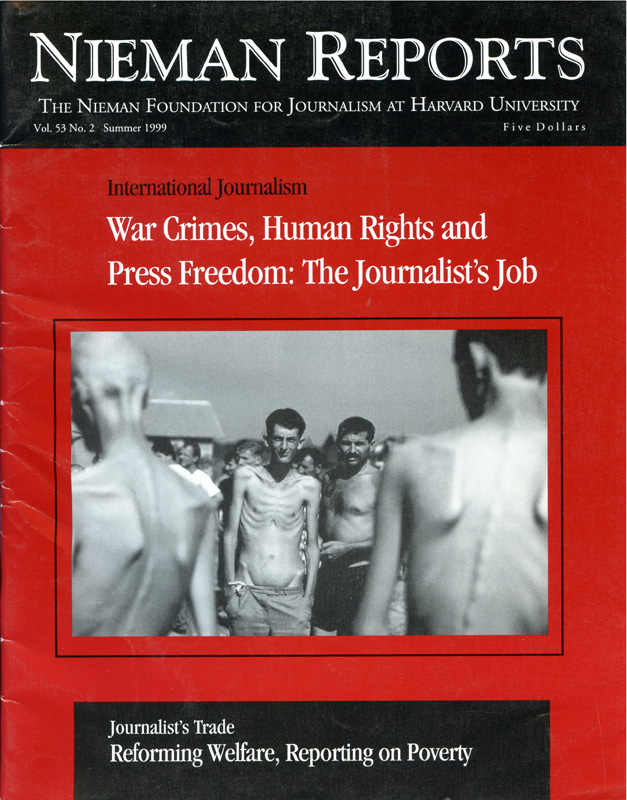

An elderly ethnic Albanian woman from Kosovo comforts a small girl in a school in Bob, a village some 50 kms. south of Pristina, as another weeps, Tuesday, March 2, 1999. The UNHCR evacuated some 350 people off of a mountainside after they fled their village two days ago because of fighting between the Kosovo Liberation Army and Serb police and armed forces. Photo by David Brauchli/The Associated Press.

Journal Excerpts

Photographer David Brauchli is documenting the Kosovo crisis for news organizations, as he did during the Bosnian conflict and in other war zones, such as Chechnya. As he works to visually convey what is happening to the people who are victims of these wars, Brauchli keeps a written journal. It is his way of trying to absorb all that he and other journalists observe and confront as they tell the stories of war.

By David Brauchli

“Paranoia had been gripping Pristina, capital of Kosovo, since U.S. negotiator Richard Holbrooke walked out of a meeting with President Slobodan Milosevic and announced that he had failed to secure a peace deal. Actually, since the OSCE pulled their monitors out of Kosovo, the situation had rapidly deteriorated, but it was possible to still the paranoia and work. But when Holbrooke left, it became impossible.

“Wade Goodard, a freelance photographer for Newsweek and The New York Times, and I were walking down the street. A bread line had formed as people, both Albanian and Serb, realized the air strikes, threatened for so long, were about to become reality. I wanted to shoot the people standing in this bread line, not a difficult thing, but I couldn’t work up the courage to raise my camera. There was an evil in the air, an uneasiness, paranoia. I couldn’t tell who was Serb, who was Albanian. I got Wade to stand in front of me and banged off a few frames on a long lens and then ducked behind a truck.

“Wade, on a shorter lens, went up to the crowd, but as he started to shoot, a man yelled at him, ‘Hey, what do you think you’re doing?’ And a woman started to yell, ‘What are you taking pictures of?’ We scurried away from the line, the accusing looks, the wicked, evil feeling.

“But the feeling didn’t abate. It grew. And more rumors fueled the paranoia.”

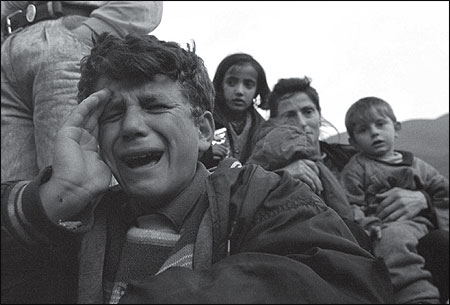

Vebi Regigoi, from Kacanik in southern Kosovo, Yugoslavia, cries after being expelled from his home by Serb army and police forces after arriving in Albania at the Morini border crossing on Monday, March 5, 1999. He and his family were expelled from their homes and bused across Kosovo to Albania by Serb police. Photo by David Brauchli/The Associated Press.

“Walking through the roadside camps, I am overwhelmed. I have been to many of the towns and villages where the refugees are from. I understand their attachment to their ancestral homes, to the land and to the beauty that is Kosovo. I empathize with the dispossessed. I feel bad as I see them queue desperately for bread and milk. I think it is demeaning for these people to queue for food. It’s awful to watch as children eat prepackaged rations that are meant for soldiers in a war. It is the humiliation, or worse, of one race by another.

“When I see a small child wait, a mother silently weeping, a man too shaken to string together a coherent sentence, his hands shaking as he grips his tractor’s steering wheel, I am appalled and saddened. And yet, when I tell that same man that I am from America, his face lights up, hope gleams in his eyes, his hands steady and he asks me, ‘When are the troops coming?’ When, indeed?”

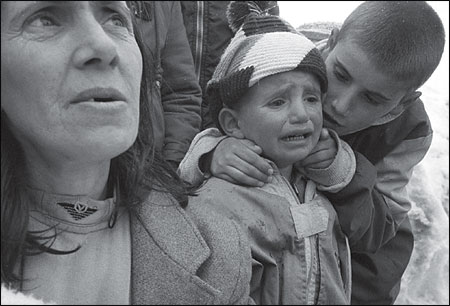

A young Kosovar boy comforts his brother crying for his father after walking out of Pec along a snowy road which goes to neighboring Montenegro on Wednesday, March 31, 1999. Thousands of refugees continue to flood out of the embattled province towards the Montenegran border on foot, by tractor or in cars. NATO said it was expanding its bombing campaign in Yugoslavia as Western powers rejected a peace bid by Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic. Photo by David Brauchli/The Associated Press.