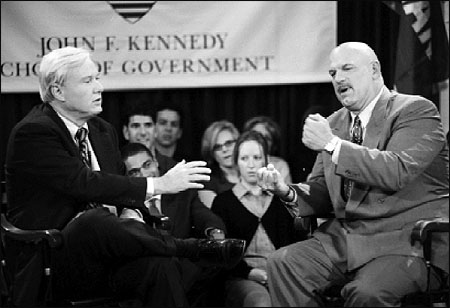

Minnesota Gov. Jesse Ventura (right) punches the air as he talks with CNBC television talk show host Chris Matthews at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government in October 1999. Photo by Jon Chase/Harvard News Office.

When Minnesota Governor Jesse Ventura gave a speech to the Minnesota Society of Professional Journalists last May, he said he wanted to call it “I Hate the Media.” But the title wasn’t quite right, joked the governor, so he changed it to “How I Hate the Media.” The reporters in the audience laughed, but for the dozen or so journalists who cover the governor regularly as part of the Minnesota capitol press corps, the joke has long since worn thin.

On election night, November of 1998, Ventura exclaimed that his Reform Party victory “shocked the world.” It also shocked the state’s political and journalistic establishment. The press certainly covered Ventura’s campaign. He has acknowledged that the “free media” exposure he got in debates, on talk shows and in other forums, helped his under-funded effort gain the advantage over his more experienced and well-heeled opponents. But reporters covering that race never really expected Ventura to win. Until the closing weeks of the campaign, journalists generally treated him as an entertaining sideshow, as a diversion from the more serious candidates, Republican Mayor Norm Coleman and Democratic Attorney General Skip Humphrey.

For weeks after his surprise victory it was virtually impossible for anyone in Minnesota to turn on the radio, the TV, or to pick up a local newspaper without hearing, seeing or reading something about their maverick new governor. It had become a feeding frenzy. And the media gorged themselves. This burst of excessive coverage might be one reason why the governor now complained that the media covers him only to sell papers and increase ratings.

Now, as Ventura is well into his second legislative session, relations between him and the press corps are openly hostile.

Jim Ragsdale, who has covered state government and politics for the St. Paul Pioneer Press since 1994, puts the blame for the rift on the governor. “He has a deep abiding mistrust of the media,” says Ragsdale, “and the closer the media is to him the more he distrusts them.”

WCCO-TV reporter Pat Kessler has worked at the capitol for 15 years and covered four Minnesota governors. He says reporters have a love/hate relationship with Ventura. “We love him. He hates us.”

Star Tribune reporter Robert Whereatt has covered the Minnesota capitol for nearly 30 years. Ventura, he says, “doesn’t trust us. I don’t think we’ve given him reason not to. His image has been aided by the media from the very start.”

Friction between politicians and reporters is nothing new, but veteran journalists say it’s different with Ventura. The reporters’ biggest complaint is that Ventura does not do interviews. Kessler keeps count. Since the beginning of the governor’s term he has asked 44 times for a one-on-one interview. The governor has agreed three times. Kessler believes a part of the problem might be that he refuses to agree to ground rules the governor’s office tries to set for the interviews. Ventura’s press staff, Kessler says, has asked him to limit his questions to one topic or to provide questions in advance.

Kessler says it’s a difficult situation, because Ventura is such good copy. “In any interview the governor will make news on three or four topics,” he says, “and at least one of them will be controversial.”

Minnesota reporters find it especially galling that while Ventura refuses to talk one-on-one with journalists who cover the daily workings of state government, he seems to go out of his way to do interviews with the national media. He’s become a fixture on the Sunday morning TV talk shows and has appeared on shows such as “Regis and Kathie Lee” and “Montel.”

Ironically, it was an interview with a national magazine, not the local press, which led to the biggest crisis in Ventura’s 15 months in office. His popularity in statewide polls plunged after he told Playboy that he considered organized religion a “crutch for weak-minded people.” In the interview he also labeled suicide victims weak and said that, if reincarnated, he would choose to come back as a 38 double-D bra. Ventura has since gained back some of the ground lost in the polls, but members of the legislature say the governor has lost much of the luster of his first year in office.

In a February speech to the Colorado Press Association, Ventura complained about how the local press reported the Playboy interview. He charged that it was “sloppy journalism” for headlines to say “Ventura Defends Tailhook Scandal.” The governor said he made it clear in the interview he did not condone the Navy officers’ conduct and that he could understand why some pilots who put their lives on the line would consider sexual harassment allegations “much ado about nothing.”

The St. Paul Pioneer Press’s Ragsdale has noticed that frequently Ventura will refuse an interview with a local reporter on a topic he will then freely discuss on a national talk show. He says Ventura’s popularity as a politician who is regarded as a national celebrity hurts Minnesota voters’ chances to get more information on the governor’s policy priorities. “The difference with Ventura” from previous governors, says Ragsdale, “is that his words are in demand. He has more interview requests than he could possibly accommodate, whereas most governors in the country would be happy to talk to the local paper to get their message out.”

WCCO’s Kessler says he believes Ventura is reluctant to talk to local reporters because he doesn’t want to display his lack of knowledge about the intricacies of government. Kessler says Ventura is the hardest working governor he’s covered, but that when he took office Ventura “knew almost nothing about how government operates.” Kessler believes Ventura doesn’t want to be publicly embarrassed, and that the national TV interviews are easier for the governor because they don’t get into such details. “The first and second questions are fine,” says Kessler. “It’s the fourth and fifth he has trouble answering.”

Not surprisingly, Jesse Ventura denied an interview request for this article. He has, however, given several speeches and made several comments about his relationship with the media. On a radio talk this month he complained, “They [the media] don’t verify anything. If it’s sexy, if it’s titillating, they write it. It doesn’t matter if it’s true.” The comment came in response to a question about how the governor can continue to say he returned the state’s entire budget surplus to taxpayers last year, despite double-digit increases in state spending.

Ventura was a talk radio host after he retired from wrestling. He apparently is still an avid talk radio listener. He’s worked out a unique arrangement with the Twin Cities’ highest rated radio station to do a weekly call-in program of his own called “Lunch With the Governor.” Ventura isn’t paid for doing the hour-long show, and WCCOAM gets to keep the revenue from the commercials. The show is unusual because there is no co-host. The governor gets the entire hour to say whatever he wants in whatever way he wants.

Reporters hate the program. The Star Tribune’s Robert Whereatt says, “It’s unedited, unfiltered. Errors are allowed to go uncorrected. And it gives him an excuse not to talk to us.”

That’s exactly the reason why Ventura says he wanted to do the show. He says he didn’t want his opinions to be filtered through the media. Earlier this year, state legislators who were upset with the governor’s unchallenged criticism on his radio show persuaded WCCO’s management to give them their own program. It will last a half-hour and follow Ventura’s program every Friday.

Ventura’s efforts to communicate directly with the voters seem to be working. The latest Minnesota Public Radio/ St. Paul Pioneer Press Poll shows 52 percent of voters in the state rate his performance as good to excellent. Minnesota’s economy continues to outperform the national economy and the state budget is running a $1.8 billion surplus. Even the journalists who are upset with their lack of access to the governor aren’t willing to say the public has suffered because of it. WCCOTV’s Kessler says, “Our viewers probably don’t notice any difference. We will cover him. We will shout questions at his public appearances. But in the long term we will never know what he really thinks about the policies his administration is trying to enact.”

Mike Mulcahy is Senior Political Editor at Minnesota Public Radio. He’s covered politics and government in Minnesota for 15 years.