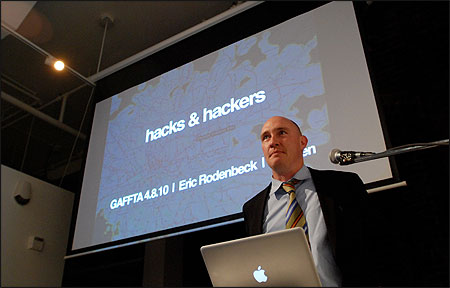

Eric Rodenbeck, founder and creative director of Stamen Design, speaks at a Hacks/Hackers event in San Francisco. Photo by Burt Herman.

The scene is often an airy loft in San Francisco’s South of Market area where technologists typically gather to talk about their latest start-up venture, share ideas, and demonstrate new digital tools. The scent of pizza wafts through the room while people Twitter away on smartphones.

Hacks/Hackers gatherings are different: Journalists are now in the mix, not to get quotes for stories but to discuss the future of media in hopes that in this time of upheaval a way forward can be found.

Hacks/Hackers was born out of a blend of hope and curiosity. I had just completed a Knight Journalism fellowship at Stanford University after a dozen years as a bureau chief and correspondent for The Associated Press. At Stanford, I studied innovation and entrepreneurship so I could learn what makes Silicon Valley tick and apply those lessons to journalism. After the fellowship, I remained in the San Francisco Bay Area to experiment with my own projects and find partners who shared my passion for the intersection of media and technology.

In November I started a group on Meetup as a way to build a community of journalists and technologists. I wanted “hacker”—a term that embodies the spirit of an engineer who does whatever it takes to get the job done—in the group’s name. “Hack,” as slang for journalist, worked in a tongue-in-cheek self-deprecating way. Hacks/Hackers was born.

It turns out I wasn’t the first person to happen upon this name. Two journalism leaders, Aron Pilhofer and Richard Gordon, who were working to bring technology into the newsroom, also had proposed an online community called Hacks and Hackers. Pilhofer, editor for interactive news at The New York Times, leads the team that builds the Web site’s data-driven EDITOR’S NOTE

Read about what Gordon’s students produced in the Fall 2009 issue of Nieman Reports »applications. Gordon, associate professor and director of digital innovation at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, oversees a scholarship program for computer programmers to earn a master’s degree in journalism and collaborate with j-school students in the process.

At a conference last year in Cambridge, Massachusetts, organized by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the MIT Center for Future Civic Media, Pilhofer and Gordon pitched the idea of creating a Hacks and Hackers Web site for this emerging community of journalists, programmers and journalist/programmers.

As our gatherings in San Francisco got underway, journalists noted the coincidence of our names on Twitter so we reached out to each other. All of us recognized the benefit of bringing together people from these disparate fields to use technology to help find and tell stories in the public interest.

Since then, Hacks/Hackers has launched a blog and a question-and-answer Web site where leading technologists and journalists from across the world respond to questions and share ideas. We’ve been thrilled at how much interest the Q. and A. site has generated since its launch in mid-April.

In the Bay Area, we’ve held monthly events that have brought together dozens of people from companies such as Google, Yahoo!, Twitter, the San Francisco Chronicle, San Jose Mercury News, and Current Media, along with other technology and media start-ups and freelancers. Events are spreading to more cities. In early May a group got together in Washington, D.C. in partnership with the Online News Association; similar gatherings are in the planning stages for New York and Chicago.

Toward the end of May, we met in San Francisco—partnering with KQED, the most listened to NPR station in the country—to build news applications for the iPad and tablet devices. Part journalistic exercise, part hack weekend, the journalists were charged with finding a story to tell while the engineers brought their insights and tools to find new ways to tell a story. At the end of the weekend, they presented their work to an expert panel including a venture capitalist, start-up CEO, and journalists.

It turns out that technology people are often news junkies. The most skilled hackers are good at what they do because they can quickly consume information and learn how to do something new. Hackers, like journalists, believe strongly in freedom of information, embodied in the open nature of the Internet. When Twitter held its first conference for developers in April, CEO Evan Williams said the company was guided by the fundamental philosophy that “the open exchange of information has a positive impact on the world.”

Still, the conversations between hacks and hackers haven’t always been harmonious. At a Hacks/Hackers panel in February with companies that build personalized news aggregation sites, entrepreneurs faced a barrage of questions about how to fairly compensate content creators for their work. But the panelists themselves admitted that they weren’t making any money.

We’re all trying to figure out what works, and that’s really the key to innovation: a tolerance for failure and embrace of experimentation. At its core, that’s what Hacks/Hackers is all about.

Burt Herman has reported from around the world as a bureau chief and correspondent for The Associated Press. A 2008-2009 John S. Knight journalism fellow at Stanford University, he tweets @burtherman.