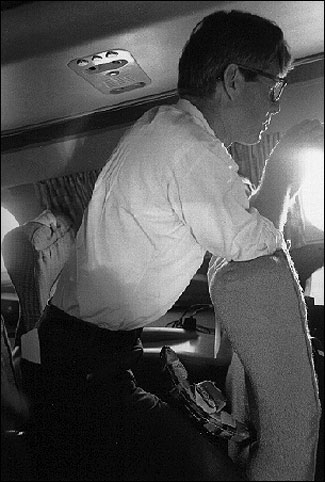

Robert F. Kennedy, 1968. Photo © Burton Berinksy.

Political campaigns have found different ways to influence the press over the years. Joseph Kennedy, father of John and Robert, sometimes used cash. In 1952, when JFK was running for the senate against Henry Cabot Lodge, the elder Kennedy secured the endorsement of the Boston Post, a then influential newspaper, by loaning the publisher half a million dollars. Joe Kennedy’s sons took a more subtle approach. They invited journalists into their confidence and won them over with disarming frankness, asking political and personal advice and sharing gossip, often in a humorous vein. Some years after the 1952 election, Fletcher Knebel of Look magazine asked JFK about the rumors surrounding the endorsement of the Boston Post. “Yeah,” said Kennedy, “We had to buy that paper.” Kennedy knew that he could trust Knebel not to print his deadpan response. Knebel had covered Kennedy for years, usually on friendly terms; he simply understood that such remarks were off-the-record.

No politician today would make such an assumption, or dare to be so candid, even in a joking manner. Watergate and Vietnam effectively ended an era of trusting relationships between politician and reporter. To some degree, the new confrontational rules better serve the voter. The old coziness made it easier to manipulate reporters, to lull them with false honesty, and dull their inquisitiveness with a joke and a slap on the back. The intensely adversary nature of the relationship between a presidential candidate and the press almost guarantees that the American people will not elect a President with a dark secret in his past.

But the “gotcha” culture has come with a price. For all their constant psychoanalyzing of political candidates, reporters may actually know less than they did in the days when a candidate could share a drink and some inside chat with a reporter without reading it in the papers the next day. Increasingly, candidates for high office, particularly the presidency, have withdrawn into a cocoon of handlers. The press has come to lionize and over-dramatize the senior campaign strategists and advisers—who often do become friends with reporters—while failing to truly understand the essential character of the candidates themselves. This distancing grows worse if the candidate wins. The White House in recent presidencies has become a bunker, surrounded by bristling guardians, furiously spinning and stonewalling.

The 2000 campaign has provided an exception to the rule. While other candidates were keeping reporters behind rope lines, John McCain was holding forth for two or three hours a day, on-the-record, and taking any question a reporter wanted to ask. McCain cracked jokes, teasing reporters as “Trotskyites,” and laughingly saying that his media adviser “looks like he’s just out of prison on work release.” But he also spoke seriously about his views on the issues. McCain’s extraordinary openness worked to make him popular with reporters and also to get out his message. In January, a study by the Washington-based Project for Excellence in Journalism found that 40 percent of McCain campaign stories were about what he had to say, compared to 26 percent for George Bush. The Bush stories tended to focus on the horserace, the basic staple of modern political coverage. The media’s obsession with the mechanics of the race—handlers, polls, tactics—is generally a turnoff to voters. “We [the media] don’t seem to see the race as a clash between men and ideas,” Tom Rosenstiel, the project director, told The Washington Post. “We seem to see it as a race between handlers and strategists.... It tends to make the race less relevant to voters.”

I thought about these contrasting models in political coverage this winter as I finished a biography of Robert Kennedy, while at the same time pondering a book-length narrative of Campaign 2000 that I will write for Newsweek, to be published on election day. I realized in writing Newsweek’s 1996 campaign narrative that as journalists following the old Teddy White model of offering the “you are there” campaign narrative, we were complicit in overstating the role played by the handlers. We need heroes and villains for our story, and if the candidates themselves were unavailable, their surrogates would have to do. I hope to guard against that somewhat lopsided view this time around, but it can be hard to see past the handlers, posing and posturing for their pals in the press, to the candidate within.

The extreme example of the old model was the 1968 Robert F. Kennedy campaign. During the 80 days between RFK’s announcement in March and his death in June, the Kennedy campaign plane became a rollicking caravan, an almost too-interwoven bonding of candidate and press corps. The traveling press teased and sang and partied with Kennedy as they marched from Indiana to Nebraska to Oregon to California. In one extraordinary scene, described in an oral history by Life magazine reporter Sylvia Wright, the reporters and RFK collapsed together, like a pack of hounds, in the front of the plane on a night flight to Oregon, exhausted from singing folk songs together after a hard day of campaigning. Imagine a presidential candidate today lying down and nodding off with jackals of the press! RFK did not view the reporters who covered him as adversaries, or even, really, as reporters. “Bobby had felt about us like we were not the press,” Wright recalled. “He would say to us, ‘When we land here, I’m not going to be ready, keep the press away from me.’ What he meant by ‘the press’ was strangers from the local press that he didn’t know.”

Robert F. Kennedy, 1968. Photo © Burton Berinksy.

In that freewheeling era, it all seemed spontaneous, a 1960’s “happening”—except that it wasn’t really. RFK had about 20 years of practice at stroking reporters. As Chief Counsel to the Senate Rackets Committee in the late 1950’s, RFK routinely traded information about labor corruption with investigative reporters and hired some of the best—Ed Guthman, Pierre Salinger, John Seigenthaler—as aides. As Attorney General, RFK remarked that he spent most of his time in the first few months talking to reporters. Kennedy was very open with the newsmen. He invited them out to Hickory Hill to swim in his pool and play touch football and asked, with evident sincerity, their advice on policy matters. When the Justice Department was involved in difficult and intense negotiations to end segregation in Birmingham, Alabama, in the spring of 1963, he allowed a reporter from the Birmingham paper—hardly a likely ally—to sit in on his strategy sessions. By showing he had nothing to hide, and by subtly making reporters feel like members of his team, Kennedy won the trust and admiration of many newsmen. In return for access, reporters routinely showed their stories to Kennedy in advance of publication—something most reporters would not do now.

When Kennedy announced that he was running for President in March 1968—a few days after Eugene McCarthy shocked President Lyndon Johnson with a strong showing in the New Hampshire primary—many reporters regarded the New York senator as a “ruthless” opportunist. But Kennedy was able to win over even the most hard-bitten newsmen who covered his campaign. John Harwood of The Washington Post, a crusty ex-Marine, criticized RFK for demagoguery in an early story, so infuriating the candidate’s wife that she threw a balled-up copy of the newspaper in his face. But after traveling, playing touch football, singing and drinking and joking and talking with RFK for two months, Harwood felt compelled to call his editor, Ben Bradlee, and ask to be moved to a different beat. Harwood honestly confessed to Bradlee that he had lost all objectivity.

Kennedy was able to maintain a strict discipline among reporters: Anything said or done on the campaign plane stayed there. (An AP reporter was kicked off the plane for writing that the candidate, conserving his hoarse voice, had signaled a stewardess for a drink by drawing an “S” in the air, for Scotch.) Watergate and the Washington scandal culture it spawned doomed such discretion. Washington hostesses began lamenting that “there is no such thing as off-the-record anymore.” Off-color or ad hominem remarks made over dinner tables began appearing in print. Nor surprisingly, many politicians and policymakers began staying away from social gatherings where a reporter might be present. Conversations became more guarded and banal.

The news did not dry up, of course. Reporters merely looked for new ways to get information. In politics, they often turned to the handlers—the campaign managers, media advisers, professional pollsters—who were taking an increasingly assertive role in election campaigns. Reporters were willing to make implicit bargains with the aides. Campaign advisers would feed the reports inside tidbits, polling data, and “oppo,” opposition research. Reporters would protect their sources and more—they would often magnify and enhance the strategic or tactical brilliance of the men and women behind the candidate. A casual reading of the coverage of the ’92 campaign would reveal that the true heroes were not Clinton and Gore—but rather Clinton’s chief advisers, James Carville and George Stephanopoulos. Within a few years, Carville and Stephanopoulos had dropped any pretense of playing their roles behind the scenes: They were media giants on the lecture circuit and regulars on the talk shows.

Typically in a modern presidential campaign, the candidate floated off in middle distance, often a figure of obstinacy or even buffoonery to his own staff. The more cynical handlers treated their bosses as nuisances who got in the way of efficient, well run campaigns. Candidates to them were like children, to be brought out and paraded around before bedtime, then sent to their rooms. They had to be kept “on message.” Extraneous remarks were dangerous, and hence frowned upon. A gross example was the ’96 Bob Dole campaign. As a senator, Dole, a wry old hand, had a good relationship with reporters. But on the campaign he was treated as a problem child by the hired guns who had been imported to package and sell him. Dole was increasingly kept away from reporters, lest he embarrass himself. After a while, the reporters, many of whom had not known the real Bob Dole, were showing Dole the same condescension that his handlers did.

Part of John McCain’s appeal in the 2000 campaign has been that he rebelled against this model (which he witnessed first hand; McCain often traveled with Dole in ’96). McCain’s free-floating press conferences on his campaign bus have had some of the same we-are-family feel as Bobby Kennedy’s 1968 campaign plane, though in fact McCain was taking a much greater risk, since everything he said was on-the-record. Even so, reporters felt protective of him. They were beguiled by his self-deprecating charm and warmed by the feeling of “insiderness.” His playful insults made them feel like friendly combatants and forget or overlook ideological differences. In a reversal of form, reporters tended to downplay rather than exaggerate his gaffes. While other campaigns would elaborately strategize ways to handle the candidate’s missteps, McCain would typically make an off-the-cuff joke about it or simply admit error and move on.

Despite McCain’s success with the Straight Talk Express, the McCain model is not likely to create a widely followed precedent. It’s true that Bush, following McCain’s example, has tried to be somewhat more open with reporters. After New Hampshire, the curtain separating the candidate from reporters in the campaign plane swung open, and Bush began bowling oranges down the aisle and chatting up reporters. But bowling oranges is an old boys-on-the-bus stunt, and Bush stayed off-the-record. Al Gore was reasonably accessible to reporters when he needed them—when he was trying to recover from a slow start in the summer and fall of 1999. But as soon as he pulled safely ahead of Bill Bradley, he barely acknowledged the traveling press. Bradley steered clear of reporters when he was on the way up—and on the way down.

Most handlers still believe that their candidates are too inept and gaffe-prone to be allowed out amongst the reporters, at least for long stretches on- the-record. Future candidates themselves may be tempted to try to emulate McCain—but maybe not. After the New Hampshire primary, I ran into Bob Dole and asked him about his experience in 1996. “They kept me up front in the plane, away from the press. That was a mistake,” he said. Then he thought back. “I did open up once to Kit Seelye [who was covering the campaign for The New York Times]. That,” he recalled with a rueful smile, “was also a mistake.” As long as candidates and their handlers believe that there is more to be gained from spin than openness, the McCain model will remain the exception and RFK’s 1968 campaign a distant memory.

Evan Thomas is Assistant Managing Editor of Newsweek. From 1986 to 1996, he was the magazine’s Washington Bureau Chief. His biography of Robert F. Kennedy will be published in September by Simon & Schuster.