Walter Bender is the executive director of the MIT Media Lab, where he directs the Electronic Publishing Group and is a member of the laboratory’s News in the Future consortium. He also directs Gray Matters, a group that focuses on technology’s impact on the aging population. At this conference, Bender spoke about what technology will and won’t do to address some of the challenges that news organizations confront. Edited excerpts of his remarks follow.

Photo from www.arttoday.com ©2002.

Walter Bender: If the topic of today’s meeting is who’s going to pay for the news, I’ll tell you right now that technology is not going to pay for the news. Technology is going to impact your business and your industry in big ways, but it’s not going to pay for the news. But I can tell you a bit about some of the things that I think technology is going to do and some of the ways in which it might impact you.

There are ways in which technology impacts efficiency. There are ways in which technology impacts your organizations in terms of how they’re organized and how they do what they do. But it’s not going to change the basic equation. You’ve got to have a product people are interested in. If you’ve got an audience that’s engaged in your product, everything else follows from there. If you’ve got an audience, you can have advertising and you can offer services. But unless you’re actually engaging people and unless you’re actually offering something somebody’s interested in, none of the rest of it matters.

What I’ve been thinking about more and more during the last four or five years is not so much how do we do this stuff, but why do we do it—not how do we engage in the future of news, but why do we care about news and how do we make news be a product that’s something actually of interest and utility to people? Without that, you’ve got nothing. So I’ve been thinking more about what’s news for and it’s actually been leading me into developing a series of experiments that aren’t going to thrill you, but I think that they’re really important and they do make a difference.

RELATED WEBLINK

The Melrose MirrorFor the last five or six years, Jack Driscoll, who used to be editor of The Boston Globe, has been working with me on a project called Silver Stringers. We put together a relatively simple tool to enable a group of senior citizens (60-, 70- and 80-year olds) to publish their own newspaper. The original Web site is called The Melrose Mirror, and they’ve been going at it since 1996. This group of seniors gets together two or three times a week and argue with each other—we think of it as a very passionate engagement—and it’s about news. Now, it doesn’t happen to be about your news. It happens to be about their news. But they are engaged in news as a concept, as a commodity, as an idea. News is important to them; it’s part of their lives in a way that it never was prior to this. And I think there’s a lesson to be learned there.

A couple of observations just about the particular technology that makes all of this possible. It’s relatively low tech. It just uses vanilla HTML. What it does do is mimic the process associated with the news. There is a little menu item on FrontPage called publish. You make your page, pull down the publish menu item and click, and your page goes off and it’s published on the Web. How many of you—and you’re all relatively senior within your organizations—have unilateral ability to go and put something on the front page of your newspaper without any checks or balances, nobody else to look at it? It’s not the usual in your industry. Usually what happens is there’s this relationship between writers and editors and editors and publishers. There’s a process associated with publishing the news.

We built into the tool a process, a flow. And that process forces people to engage with other people. The tool forces them into a social interaction right out of the box. I don’t believe that that really is the case with any of the other tools. And it’s a simple thing, the most natural thing for people in the news industry, but it’s really foreign to the way in which everybody else operates. That’s just fundamental to the process, right from the very beginning. And I think that’s the thing that makes the difference.

It turns out that process is really important for one thing—it’s important for quality control. It takes time for these communities to learn the process, to learn what you all have taken a lifetime to learn and master. But they go from a stage of participation to one of appropriation. And so this really does become theirs. And they learn to the extent that they’re putting out something that’s pretty high quality.

They can write. And they can tell stories. And they can express themselves. And they’ve discovered that writing and storytelling and expression is a very social thing. So they really do need to get together three times a week and have this argument. It’s really fundamental to what they do now. And maybe this is the encouraging thing—By any and every measure, even though they are engaged in making their news product, The Melrose Mirror, they’re as engaged and more engaged than ever in traditional news media. They write more letters to the editor of The Boston Globe than they ever did before. And not only do they write more letters, but also they get their letters published because they’re well crafted and right on target. They’ve discovered through practice that news means something to them. It is not just the stories they tell but their engagement in the world.

If anything, that is what technology is doing to your business. It is empowering the consumer to have a voice. As I’ve been watching your industry’s reaction to technologies such as the Internet for the last 10 years, your industry is fundamentally dismissive of these phenomena. I can’t say that strongly enough. You are fundamentally dismissive of the consumer having any kind of intelligence. But, in fact, the consumer is really an intelligent, capable part of the process, and you need to engage the consumer.

Right now there is more content being produced in Web logs on a daily basis than all of Reuters, A.P., The New York Times, and Tribune service combined. One of my students has put together a site called blogdex, which is building an aggregator for all the Web logs to bring this community together. It’s also giving them a voice that I predict will be competitive with those media organizations. You want to embrace this phenomenon and channel it to be part of what you do and be part of the engagement and service you offer communities you serve. It sounds trivial and sounds inconsequential, but it is the next big thing.

My big beef with the news industry during the Internet bubble was that I can’t think of a single U.S. news organization that actually thought about their online asset as an asset to the news organization as opposed to a potential IPO. Maybe you’re going to make a lot of money selling this thing, but it still has the potential of fundamentally changing the way you do business, changing the way you relate to your customers.

There actually are some useful, important things that technology does bring to the table. Is it going to pay for the news? No. Is it going to be part of the equation that keeps your audience engaged? Absolutely. Take the consumer seriously. The consumer is intelligent. Give the consumer the opportunity to learn. There’s a lot of potential to leverage the amateur out there. And some of the amateurs are pretty good, and even if they’re not perfect at their craft, they’re probably experts in what they do during their day job and you want that resource as well.

The journalist becoming an expert for 24 hours about a topic and then moving on to the next topic—that isn’t sustainable. It doesn’t have credibility anymore. So you’re going to have to figure out a different model. There is this opportunity to engage at a much deeper level by leveraging the fact that people like to tell stories and can learn to be good at telling stories and telling them is important to people. That’s really what technology has to offer.

Artist’s rendering courtesy of Boeing Satellite Systems, Inc.

Bender’s comments brought forth a range of responses, including many who questioned some of his overarching points.

Conor O’Clery: You said that the day when journalists can master something in 24 hours and become an expert on it is going to pass. Well, I think the talents of the best professional journalists are precisely that they can do that. They have got to master a lot of information very quickly and that’s their talent. That’s one of the essential talents of a professional journalist. You threw out a phrase about Web logs that that really is the next big thing. But nothing you said convinces me that it’s the next big thing. So I was wondering if you could expand on that a bit?

Bender: I do not use the press or journalism as a way to find out what’s going on in my industry. Period. It’s not what they don’t know; it’s what they know that just ain’t so. They’re not good enough. I don’t believe that there is sufficient talent out there to do what you described, and I think that the talent lies elsewhere, and I think we need to tap into that. We can disagree about that. But in my experience, it’s just not there. Certainly when somebody is sticking with city hall for their career and they know city hall inside out, and the reporter has got the time to stick with something and knows how to ask hardball questions, those are all good things, and presumably that reporter is very good at taking an idea and expressing it succinctly. But I think you need to get deeper, and I don’t see that depth coming from journalism as it’s practiced today.

I think the industry has already come to the realization that what they have to offer is more than just a product. It’s also a collection of services. There’s actually a lot of value in an organization that could be spun out as services and value added to a variety of different markets. And that’s just going to happen. That’s just a smart thing to do.

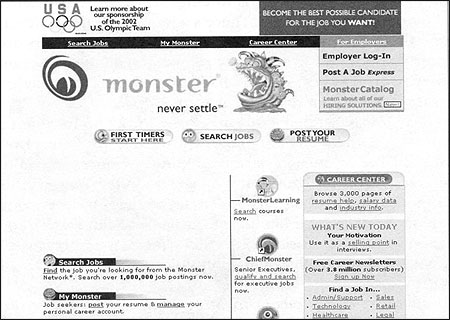

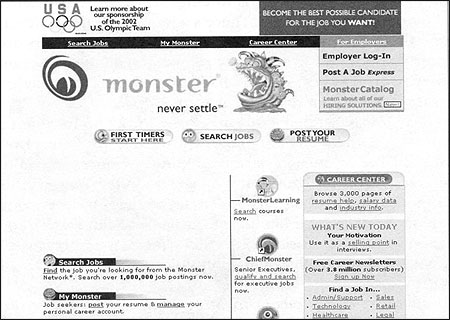

Web page courtesy of Monster.

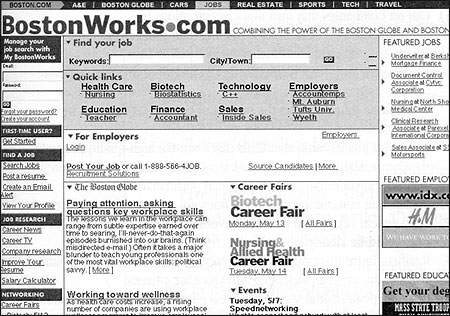

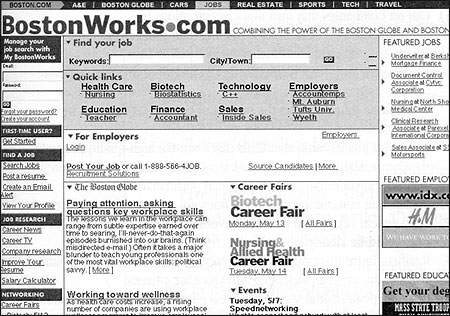

Web page courtesy of Boston.com.

By the next big thing I mean that I think that the rest of the world is beginning to get a voice and to get a taste of being expressive. They’re learning how to do it. And they’re learning what journalists know how to do. They like it, and they’re getting to be good at it and they’re doing it more and more and more. I think that is the next big thing. Right now it’s being expressed in little things like The Melrose Mirror. I think it is a phenomenon, but it’s going to take time. Maybe it really will take the generation that’s been growing up with e-mail all their lives.

The point is that if you’re going to get your audience to continue to be engaged with news as something that’s part of their lives, I think the way to do that is to get them engaged in news, and get them engaged in the process, not just some product. And I think that that’s fundamental to keeping people interested.

Crocker Snow: If you run this string of your argument out all the way, does that mean we engage people in the news by creating it more and more and it’s inexorable and inevitable? So when you run that string out all the way, we become stringers of that news they’re creating, not creators of it at all.

Bender: No, I don’t think it needs to run that way. There are a couple of things that are always going to happen. We’re always going to need editors because we’re always going to need somebody to help organize and orchestrate. So I think we’re a long ways from when I can do it all with Google, even if the ratio of editor-to-journalist changes dramatically within your organizations, and I think it actually will. I think that you’re going to be doing much more editing and much less original writing within your publications.

Jeff Flanders: In research I’ve seen from Nielsen, most people can handle seven channels of television, and I suspect the same thing is going to occur for the Web as well. And I would challenge the model you’re describing, because I think it takes too much effort. Let’s take something like air safety. I think most people would rely more on someone who was deeply steeped in that subject rather than relying on the black helicopter theories that are going to float around the Web. So I think there is a role for expert knowledge, and I think there is a role for the journalistic thing. And I think people do want that gatekeeper function performed for them. It’s a valid one.

Bender: I don’t think that anybody, even me, said anything about not having good editorial decision-making happening. The model I described for self-publishing is all about editing. It’s not self-publishing. It’s community publishing, and there are communities of people working together around stories and topics.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter: I think there’s certainly something about this new technology’s community-forming potential, about its interactivity, about the fact that consumers can talk back. In fact, in addition to Amazon.com’s peer reviews of the reviews, there is also a growing phenomenon on the Web of organizing and complaint sites. One of the few companies to get investment after the first dot-com crash in April of 2000 was Planet Feedback.com, which was all about getting your complaint e-mailed to the company and also to your congressional representatives. It was so interactive. Each one of these things are potential ways to use the technology. Lots of this is application driven; it is not what’s inherent in the technology. A lot of these things are limited only by our imagination. But the e-organizing—that’s how the anti-globalization protests were organized, on the global interactive media.

Margaret Holt: Come back to your original point, Walter. What’s the news for? I think one of the things that spins off of saying what’s news for us is that it’s easy for us to organize and think about how we want to deliver the news. What we don’t think nearly enough about is what people want it for and about the communities that they define in their own ways and how we can be more connected with that. I think that essential point that you made is incredibly powerful.

Bender: But there’s another piece to it. All of us as consumers are going to have tremendous resources, and you want to work with us through those resources as opposed to ignoring this factor and assuming that, “Well, I know better.” You want to take advantage of the fact that I am willing to engage. I take issue with the conventional wisdom that says people don’t want to engage, that people want to sit back and be told. I challenge that fundamental assumption, and I think that’s going to change. It won’t change absolutely, for all time and for all people. That’s ridiculous. But when it happens, it matters, and when it happens and you’re responsive, then you’ve got me. But when it happens and you’re not responsive, I could care less.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Technology Builds Context"

- Walter BenderKen Doctor: As journalists, we always push toward dichotomy. I’m an editor; it’s probably one of my main identities in life. And I agree with what you’re saying. Most people, most of the time, want someone to deliver them products and that’s the world that we are in. I think editors will have a great time on the Internet soon. At the same time, you can see what’s happening on the Internet just by these tools, many of which are not very good, being out there and how people have used them. We have no idea yet. Our ability to bring those worlds together is there as journalists, for us to help organize communities or help other people organize communities. We don’t think of it that way. But these worlds will come together. It’s interesting to me after a couple days of thinking about what we’ve been through, in truth, I don’t think the newspaper industry is going to do it. We are so stuck in who we are, where we have been, and we can do what we do well.

Bender: There was an editorial in The Boston Globe about two or three months ago complaining that there aren’t any good online calendars or ways to find out about events around town. So I wrote a letter saying, “Huh? Come on guys. Isn’t this your job? Isn’t this what you’re supposed to be doing? Actually going out there, finding out what’s going on, being an aggregator, making it accessible to your community?” They don’t get it. It just would never occur to them that that’s their job.

Photo from www.arttoday.com ©2002.

Walter Bender: If the topic of today’s meeting is who’s going to pay for the news, I’ll tell you right now that technology is not going to pay for the news. Technology is going to impact your business and your industry in big ways, but it’s not going to pay for the news. But I can tell you a bit about some of the things that I think technology is going to do and some of the ways in which it might impact you.

There are ways in which technology impacts efficiency. There are ways in which technology impacts your organizations in terms of how they’re organized and how they do what they do. But it’s not going to change the basic equation. You’ve got to have a product people are interested in. If you’ve got an audience that’s engaged in your product, everything else follows from there. If you’ve got an audience, you can have advertising and you can offer services. But unless you’re actually engaging people and unless you’re actually offering something somebody’s interested in, none of the rest of it matters.

What I’ve been thinking about more and more during the last four or five years is not so much how do we do this stuff, but why do we do it—not how do we engage in the future of news, but why do we care about news and how do we make news be a product that’s something actually of interest and utility to people? Without that, you’ve got nothing. So I’ve been thinking more about what’s news for and it’s actually been leading me into developing a series of experiments that aren’t going to thrill you, but I think that they’re really important and they do make a difference.

RELATED WEBLINK

The Melrose MirrorFor the last five or six years, Jack Driscoll, who used to be editor of The Boston Globe, has been working with me on a project called Silver Stringers. We put together a relatively simple tool to enable a group of senior citizens (60-, 70- and 80-year olds) to publish their own newspaper. The original Web site is called The Melrose Mirror, and they’ve been going at it since 1996. This group of seniors gets together two or three times a week and argue with each other—we think of it as a very passionate engagement—and it’s about news. Now, it doesn’t happen to be about your news. It happens to be about their news. But they are engaged in news as a concept, as a commodity, as an idea. News is important to them; it’s part of their lives in a way that it never was prior to this. And I think there’s a lesson to be learned there.

A couple of observations just about the particular technology that makes all of this possible. It’s relatively low tech. It just uses vanilla HTML. What it does do is mimic the process associated with the news. There is a little menu item on FrontPage called publish. You make your page, pull down the publish menu item and click, and your page goes off and it’s published on the Web. How many of you—and you’re all relatively senior within your organizations—have unilateral ability to go and put something on the front page of your newspaper without any checks or balances, nobody else to look at it? It’s not the usual in your industry. Usually what happens is there’s this relationship between writers and editors and editors and publishers. There’s a process associated with publishing the news.

We built into the tool a process, a flow. And that process forces people to engage with other people. The tool forces them into a social interaction right out of the box. I don’t believe that that really is the case with any of the other tools. And it’s a simple thing, the most natural thing for people in the news industry, but it’s really foreign to the way in which everybody else operates. That’s just fundamental to the process, right from the very beginning. And I think that’s the thing that makes the difference.

It turns out that process is really important for one thing—it’s important for quality control. It takes time for these communities to learn the process, to learn what you all have taken a lifetime to learn and master. But they go from a stage of participation to one of appropriation. And so this really does become theirs. And they learn to the extent that they’re putting out something that’s pretty high quality.

They can write. And they can tell stories. And they can express themselves. And they’ve discovered that writing and storytelling and expression is a very social thing. So they really do need to get together three times a week and have this argument. It’s really fundamental to what they do now. And maybe this is the encouraging thing—By any and every measure, even though they are engaged in making their news product, The Melrose Mirror, they’re as engaged and more engaged than ever in traditional news media. They write more letters to the editor of The Boston Globe than they ever did before. And not only do they write more letters, but also they get their letters published because they’re well crafted and right on target. They’ve discovered through practice that news means something to them. It is not just the stories they tell but their engagement in the world.

If anything, that is what technology is doing to your business. It is empowering the consumer to have a voice. As I’ve been watching your industry’s reaction to technologies such as the Internet for the last 10 years, your industry is fundamentally dismissive of these phenomena. I can’t say that strongly enough. You are fundamentally dismissive of the consumer having any kind of intelligence. But, in fact, the consumer is really an intelligent, capable part of the process, and you need to engage the consumer.

Right now there is more content being produced in Web logs on a daily basis than all of Reuters, A.P., The New York Times, and Tribune service combined. One of my students has put together a site called blogdex, which is building an aggregator for all the Web logs to bring this community together. It’s also giving them a voice that I predict will be competitive with those media organizations. You want to embrace this phenomenon and channel it to be part of what you do and be part of the engagement and service you offer communities you serve. It sounds trivial and sounds inconsequential, but it is the next big thing.

My big beef with the news industry during the Internet bubble was that I can’t think of a single U.S. news organization that actually thought about their online asset as an asset to the news organization as opposed to a potential IPO. Maybe you’re going to make a lot of money selling this thing, but it still has the potential of fundamentally changing the way you do business, changing the way you relate to your customers.

There actually are some useful, important things that technology does bring to the table. Is it going to pay for the news? No. Is it going to be part of the equation that keeps your audience engaged? Absolutely. Take the consumer seriously. The consumer is intelligent. Give the consumer the opportunity to learn. There’s a lot of potential to leverage the amateur out there. And some of the amateurs are pretty good, and even if they’re not perfect at their craft, they’re probably experts in what they do during their day job and you want that resource as well.

The journalist becoming an expert for 24 hours about a topic and then moving on to the next topic—that isn’t sustainable. It doesn’t have credibility anymore. So you’re going to have to figure out a different model. There is this opportunity to engage at a much deeper level by leveraging the fact that people like to tell stories and can learn to be good at telling stories and telling them is important to people. That’s really what technology has to offer.

Artist’s rendering courtesy of Boeing Satellite Systems, Inc.

Bender’s comments brought forth a range of responses, including many who questioned some of his overarching points.

Conor O’Clery: You said that the day when journalists can master something in 24 hours and become an expert on it is going to pass. Well, I think the talents of the best professional journalists are precisely that they can do that. They have got to master a lot of information very quickly and that’s their talent. That’s one of the essential talents of a professional journalist. You threw out a phrase about Web logs that that really is the next big thing. But nothing you said convinces me that it’s the next big thing. So I was wondering if you could expand on that a bit?

Bender: I do not use the press or journalism as a way to find out what’s going on in my industry. Period. It’s not what they don’t know; it’s what they know that just ain’t so. They’re not good enough. I don’t believe that there is sufficient talent out there to do what you described, and I think that the talent lies elsewhere, and I think we need to tap into that. We can disagree about that. But in my experience, it’s just not there. Certainly when somebody is sticking with city hall for their career and they know city hall inside out, and the reporter has got the time to stick with something and knows how to ask hardball questions, those are all good things, and presumably that reporter is very good at taking an idea and expressing it succinctly. But I think you need to get deeper, and I don’t see that depth coming from journalism as it’s practiced today.

I think the industry has already come to the realization that what they have to offer is more than just a product. It’s also a collection of services. There’s actually a lot of value in an organization that could be spun out as services and value added to a variety of different markets. And that’s just going to happen. That’s just a smart thing to do.

Web page courtesy of Monster.

Web page courtesy of Boston.com.

By the next big thing I mean that I think that the rest of the world is beginning to get a voice and to get a taste of being expressive. They’re learning how to do it. And they’re learning what journalists know how to do. They like it, and they’re getting to be good at it and they’re doing it more and more and more. I think that is the next big thing. Right now it’s being expressed in little things like The Melrose Mirror. I think it is a phenomenon, but it’s going to take time. Maybe it really will take the generation that’s been growing up with e-mail all their lives.

The point is that if you’re going to get your audience to continue to be engaged with news as something that’s part of their lives, I think the way to do that is to get them engaged in news, and get them engaged in the process, not just some product. And I think that that’s fundamental to keeping people interested.

Crocker Snow: If you run this string of your argument out all the way, does that mean we engage people in the news by creating it more and more and it’s inexorable and inevitable? So when you run that string out all the way, we become stringers of that news they’re creating, not creators of it at all.

Bender: No, I don’t think it needs to run that way. There are a couple of things that are always going to happen. We’re always going to need editors because we’re always going to need somebody to help organize and orchestrate. So I think we’re a long ways from when I can do it all with Google, even if the ratio of editor-to-journalist changes dramatically within your organizations, and I think it actually will. I think that you’re going to be doing much more editing and much less original writing within your publications.

Jeff Flanders: In research I’ve seen from Nielsen, most people can handle seven channels of television, and I suspect the same thing is going to occur for the Web as well. And I would challenge the model you’re describing, because I think it takes too much effort. Let’s take something like air safety. I think most people would rely more on someone who was deeply steeped in that subject rather than relying on the black helicopter theories that are going to float around the Web. So I think there is a role for expert knowledge, and I think there is a role for the journalistic thing. And I think people do want that gatekeeper function performed for them. It’s a valid one.

Bender: I don’t think that anybody, even me, said anything about not having good editorial decision-making happening. The model I described for self-publishing is all about editing. It’s not self-publishing. It’s community publishing, and there are communities of people working together around stories and topics.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter: I think there’s certainly something about this new technology’s community-forming potential, about its interactivity, about the fact that consumers can talk back. In fact, in addition to Amazon.com’s peer reviews of the reviews, there is also a growing phenomenon on the Web of organizing and complaint sites. One of the few companies to get investment after the first dot-com crash in April of 2000 was Planet Feedback.com, which was all about getting your complaint e-mailed to the company and also to your congressional representatives. It was so interactive. Each one of these things are potential ways to use the technology. Lots of this is application driven; it is not what’s inherent in the technology. A lot of these things are limited only by our imagination. But the e-organizing—that’s how the anti-globalization protests were organized, on the global interactive media.

Margaret Holt: Come back to your original point, Walter. What’s the news for? I think one of the things that spins off of saying what’s news for us is that it’s easy for us to organize and think about how we want to deliver the news. What we don’t think nearly enough about is what people want it for and about the communities that they define in their own ways and how we can be more connected with that. I think that essential point that you made is incredibly powerful.

Bender: But there’s another piece to it. All of us as consumers are going to have tremendous resources, and you want to work with us through those resources as opposed to ignoring this factor and assuming that, “Well, I know better.” You want to take advantage of the fact that I am willing to engage. I take issue with the conventional wisdom that says people don’t want to engage, that people want to sit back and be told. I challenge that fundamental assumption, and I think that’s going to change. It won’t change absolutely, for all time and for all people. That’s ridiculous. But when it happens, it matters, and when it happens and you’re responsive, then you’ve got me. But when it happens and you’re not responsive, I could care less.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Technology Builds Context"

- Walter BenderKen Doctor: As journalists, we always push toward dichotomy. I’m an editor; it’s probably one of my main identities in life. And I agree with what you’re saying. Most people, most of the time, want someone to deliver them products and that’s the world that we are in. I think editors will have a great time on the Internet soon. At the same time, you can see what’s happening on the Internet just by these tools, many of which are not very good, being out there and how people have used them. We have no idea yet. Our ability to bring those worlds together is there as journalists, for us to help organize communities or help other people organize communities. We don’t think of it that way. But these worlds will come together. It’s interesting to me after a couple days of thinking about what we’ve been through, in truth, I don’t think the newspaper industry is going to do it. We are so stuck in who we are, where we have been, and we can do what we do well.

Bender: There was an editorial in The Boston Globe about two or three months ago complaining that there aren’t any good online calendars or ways to find out about events around town. So I wrote a letter saying, “Huh? Come on guys. Isn’t this your job? Isn’t this what you’re supposed to be doing? Actually going out there, finding out what’s going on, being an aggregator, making it accessible to your community?” They don’t get it. It just would never occur to them that that’s their job.

- Walter Bender is executive director and a founding member of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Laboratory.

- Ken Doctor is vice president/content services for Knight Ridder Digital.

- Jefferson Flanders is vice president of consumer marketing at Harvard Business School Publishing, which publishes the Harvard Business Review.

- Margaret Holt is customer service editor for the Chicago Tribune, where she manages the paper’s accuracy initiative.

- Rosabeth Moss Kanter is the Ernest L. Arbuckle Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School.

- Conor O’Clery is the international business editor in New York for The Irish Times, published in Dublin.

- Crocker Snow, Jr. was founding president of World Times and editor in chief of The WorldPaper, an international affairs publication that appeared in 24 countries and seven language editions from 1979 until late last year.