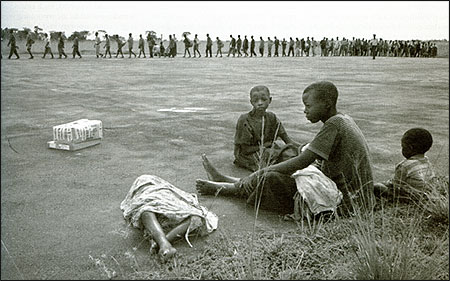

Rwandan refugees board a cargo plane in the Democratic Republic of the Congo that will take them back to Kigali, Rwanda. A mother sits next to her daughter who died on the runway of Mbandaka’s airport after walking more than 1,000 miles through the jungle for seven months. Her other children sit with her. The refugees were scattered all over the jungle when they fled massacres commited by Alliance rebel troops. Photo by Michael Robinson-Chavez, The Boston Globe.

Bosnia, Chechnya and Rwanda form a trio of disaster areas. Different worlds, different people, but common strains of ethnic and religious tension, murder and mayhem trace themselves through the history of these lands.

During the last decade, each of these areas has been manipulated by indigenous politicians who used vicious, medieval tools to consolidate their power and to remove perceived enemies and opponents. The outside world, especially the Western powers, largely stood aside when each region exploded into violence. In none of these places, where internal ethnic, religious and nationalist conflicts have arisen, can anyone say that peace has been restored.

The three books under review represent approaches typical in journalists’ books. The authors offer mountains of meticulous reporting, including the essential local histories that torture each area. As book authors, these journalists have fewer constraints in how they employ their reporting, express their personal views, and air their frustrations than they do when acting as reporters. But as often happens when journalists step outside their conventional role, they tend to wade into trouble when they attempt to analyze the politics outside the selected regions or to suggest alternatives to policies that delayed or prevented the United Nations and individual major powers from intervening. In fact, each of these authors puts their part of the world under a microscope without adequately placing their story within a broader context of post-Cold War global politics.

Bosnia is the best known of these stories since it is part of the contemporary history of the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia into its constituent republics. Chuck Sudetic takes a quite personal approach to telling this story in his book. He explores the bloody events of the war in Bosnia by linking his battlefield reporting to the lives of his wife’s extended Muslim family, who lived in a mountainous region not far from the border with Serbia. This is the same area about which Ivo Andric wrote his classic novel, “The Bridge on the Drina,” which helped him win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961. As tensions between the Bosnian Muslims and Serbs rose, locals smashed a monument to Andric that had been placed on the 16th Century Turkish bridge and threw it into the river, claiming the writer had put Muslims in a bad light.

Sudetic was an American living in Belgrade, where he had met his wife, when he began reporting on the war as a stringer for The New York Times. After five years he was given a staff job and transferred to the metropolitan desk in New York, where he was treated like most newcomers with limited experience. He decided he was not cut out for daily journalism and fled back to a tenuous existence in Belgrade, pouring his soul into this book.

“The old addiction [the war], my mania, seized me once again and I broke the promise I had made to my wife,” Sudetic recalls in the book. “I took off alone for one last stint in Bosnia for the sake of a few stories and words that might lay some living memories of the dead and of a dying world silently to rest.” His intense emotions give a strong flavor to his reporting of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the population is divided among Muslims, Orthodox and Roman Catholics. Sudetic describes particularly well the cynical manipulations of the Serb leader, Slobodan Milosevic, as he got local surrogates to carry out his “ethnic cleansing” campaign in Bosnia.

On the other hand, it is depressing to see this bright young reporter tear himself apart over his first major story. He has now left journalism and emigrated to Canada, but this profession needs more reporters like Sudetic. His experience in Bosnia also reminds us of how many significant foreign stories are being covered by “stringers” rather than seasoned staff correspondents as major media cut back on their international bureaus and staff. Thinking of this made me nostalgic for the stories sent back by such career correspondents as Bill Touhy, Don Cook, Keys Beech and Henry Mamm, all reporters who could convey the tragedy of war-torn countries without being personally destroyed by the assignments.

Like the Balkan Peninsula, the Caucasus Mountains shelter tribes in small, isolated valleys where they relive ancient hatreds and wait for opportunities to wreak revenge on enemies and rivals. Stalin and Beria, killers with no historic rivals, came from one of the larger republics, Georgia. Nearby, the people of Chechnya were viewed as fierce and anarchic; in Moscow they were regarded as successful and feared gangsters.

The Soviet-imposed order in the area collapsed with Christian Georgia and Armenia and Muslim Azerbaijan forming independent states, while smaller, less viable areas remained within the new Russian Federation. The threat that the Muslim Chechens would become independent threatened Moscow’s control over the rest of the Caucasus, stirring President Boris Yeltsin to display his muscle by sending the Russian Army down from the north.

Carlotta Gall of the English-language Moscow Times and Thomas de Waal, who reported for the same paper as well as for The Times of London and The Economist, have combined their reportage into this methodical account of the battle for Chechnya which lasted from 1993 to 1997. Like Sudetic’s book, their reports emerge from the battlefield. Unlike the young American, these two reporters kept their emotions under control while making a strong case for the cruelty and incompetence of the Russians. In this book we find little to admire about the Chechens, either, who like the Kurds not far to the south seem to live to fight and appear unable to do what it takes to organize themselves into a viable nation. The Chechens fought bravely and fiercely before they were driven from their capital, Grozny, and were forced to make peace and postpone talks about independence until 2002. They exist now as an autonomous “republic” governed by an unstable, local government in an unstable region where western oil interests collide with the regional interests of Russia, Turkey and Iran.

Despite the volatility of this situation and the possible consequences of this instability in this region, this book received little attention in the United States. This is perhaps because the book was published initially in England, but also because of the methodical style its authors use in walking us through the events of this war. Also, there seems little interest in the Caucasus region by Americans who are tired of reading and hearing about problems besetting the people in what used to be the Soviet Union.

By contrast, Philip Gourevitch, a reporter for The New Yorker, has managed with his book to garner the attention of Americans about another region that they generally ignore: Rwanda and central Africa. His book is based on six trips to this tiny, mountainous, beautiful country that held special affection for its former Belgian rulers. The genocide unleashed by the majority Hutus against the minority Tutsis in 1994 was not well covered by the American media. With few reporters stationed in Africa, the ones that were there were distracted by political events in South Africa and were late in covering the brief, bloody war.

In his book, Gourevitch sets forth the official policy in Rwanda that ignited this wave of horror and murders. “The government had adopted a new policy by which everyone in the Hutu majority group was called upon to kill everyone in the Tutsi minority. The government and an astounding number of its subjects imagined that by exterminating the Tutsi people they could make the world a better place, and the killing had followed.” Gourevitch turns his late arrival to the scene to his and our advantage as he is able to locate victims and have them retell their stories in their own words. He also tracked down some of the killers, tracing one to Texas.

Sorting through tribal histories, Gourevitch traces these peoples back to their origins, to a time before the population of central Africa was divided arbitrarily by Europeans into colonies that became Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo under Belgian rule. Some of his best reporting recounts the ugly scenes of refugees who fled west in panic from the invasion from Uganda of a well-trained army led by Tutsis determined to take control from the genocidal Hutu regime. The Hutu fighters squatted in the Congo, reconstituted themselves into a new army, and made victims of the true refugees.

Gourevitch is more of an essayist than the reporters turned authors who wrote about Bosnia or Chechnya. He relishes making historical connections to his family’s experience with the Nazi-organized Holocaust, connections that I felt appeared strained, and then reaches afar to punch Thomas Jefferson who had “leisure to think and write as grandly as he did” because of his “unrepentant ownership of slaves.” He also takes on an easy target in Washington’s unwillingness to get involved in a small, isolated African state where the United States had no compelling interests, a place too close to Somalia where the American participation in an international humanitarian operation turned into a political and military disaster.

The American public, and therefore its government, is not prepared to send its soldiers on dubious missions to faraway lands, particularly if our usual political allies have conflicting interests, as they often do in Africa. And Gourevitch can come up with no formula that would permit white outsiders to intervene successfully in black-ruled countries. Even black-led intervention forces with financial assistance from the West have not been successful in alleviating tensions in such places as Sierra Leone, the Congo or Liberia.

Rwanda remains a frightful contemporary example of officially sponsored murder and inexcusable fumbling by the United Nations and individual countries. But this failure should have been acknowledged within the context of the long history of the destructive intervention by Western nations in the affairs of black African nations. Instead, too often when journalists take on writing about these current atrocities what emerges are only glib policy prescriptions that don’t seem well-grounded in either the geopolitical realities of today or the historical roots that were planted decades ago.

While each of these books is well-written and reported, each could have been improved by incorporating these larger contemporary and historic perspectives. If readers are going to be drawn to these stories, part of their appetite for learning more about these distant conflicts will need to come out of a desire to better understand the changing dynamics of the post-Cold War era. This is a time in which America’s political, military and economic roles in regional conflicts are still seeking clear definition, and these books—in fact, news coverage in general of such conflicts—can provide important and valuable insights.

Too often, however, a weary American public is freed from the need to pay attention to such stories by a media, especially television, which have largely given up on providing comprehensive coverage of foreign news. Of course, when particular incidents carry immense shock, such as embassy bombings, or when American interests have been defined by past conflicts or present clashes, such as Israel, Iraq and Korea, news coverage is more consistent and better informed. But part of what it ought to mean to be a journalist is to confront in a responsible way the decisions about reporting on what the audience “wants” to know and what it might need to become better informed about. The positive reception Gourevitch’s book has received from critics, in particular, provides some measure of hope that the critical lessons of these distant conflicts that these and other journalists are chronicling will, in time, seep into our national consciousness.

Murray Seeger, a 1961 Nieman Fellow, is a former foreign correspondent, is Washington, D.C. representative of the Committee to Protect Journalists and Executive Director of the Newspaper Guild Committee on the Future of Journalism.