As American society grapples with growing demands for racial justice, American newsrooms are struggling with how to appropriately respond. Beyond making newsrooms more diverse, how should journalism meet the challenges of the moment and change newsroom structures and cultures that uphold oppression?

In a series of essays, thought leaders reflect and offer prescriptions for what the news industry needs to do.

No.

Strings.

Attached.

I was single. I had no children. And I was a renter.

When the discount plane fare to Japan arrived in my inbox, I flew to Tokyo on a week’s notice. When war broke out, I volunteered as a reporter to go to the front lines. I’ve had datelines from everywhere from Guantanamo Bay, Cuba to the Suez Canal to the DMZ dividing North and South Korea.

I always took my next job to explore the world, find the most compelling stories, and move up the career ladder.

Then I met Mike. We fell in love, got engaged, and married in 2012. But I didn’t just get hitched to Mike. I also became joined at the hip to his alma mater, the University of the Michigan, in my new hometown, Ann Arbor.

Mike graduated from the university more than 25 years ago, but not much has changed. He has gone to every home football game with more than 100,000 other rabid fans.

Our neighborhood is filled with the Michigan faithful. The university’s chief fundraiser, who lives two doors away, made a special point to greet us warmly. The university’s president sat beside us in the second row at the men’s basketball games.

About four years ago, I left The Wall Street Journal to join the Detroit Free Press as an investigative reporter (where I am now an editor). Trouble started innocently one morning. The paper’s higher education reporter asked me for help understanding how the University of Michigan was investing its money.

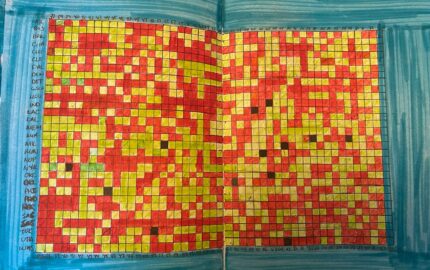

The story about a leading public university sounded juicy and important, but would it hit too close to home? I decided to dive in. Discovering thousands of pages of U-M’s financial records stored in hundreds of cardboard boxes enabled me to create a database of every published investment made by U-M since 1998.

Soon I found evidence about key executives at companies controlling university dollars. Many of those executives were also major donors to the university. Experts called it a major conflict of interest.

Billions of dollars were at stake. I found the university also hoarded money in funds controlled by donors while some students were scraping to get by.

At home, during the months of reporting, Mike had questions: “Of all of the stories you could have done, why choose Michigan? And didn’t every big university do it? Was it illegal? If not, what was the big deal?”

I didn’t feel comfortable telling him what I had found until I published. But I was anxious.

Living in Ann Arbor, living with Mike, every word of every story would be subject to scrutiny by the Michigan faithful.

When we published our stories, the impact was immediate. The university criticized our reporting, complained to the paper’s editor, and demanded retractions and apologies. But we stood by our stories and didn’t issue any corrections. And the university under pressure enacted reforms. Whistleblowers inside the university leaked internal documents to us about more financial problems. More stories came and more reforms followed.

Finally, we found two members of the university’s board of directors had accepted political donations from those who had received university investments. They lost their re-election bids after the stories came out.

What about the impact closer to home? Jerry, the university’s fundraiser, stopped waving to me when I walked our dogs by his house (He has warmed up since his retirement.). The university president fell silent as he shuffled by my basketball seats.

I realized there was a new cost to this kind of watchdog reporting. I was confident the stories were a public service, but was it worth making myself an outcast? I had faith in the work I’ve done that the tradeoff that would be worth it. And the extra pressure I felt to make sure every word and headline was accurate and in the right context only helped my journalism.

As for Mike? He learned more about why I did what I did and in the end thought I was fair and balanced. When the stories received acclaim with readers and contests, he said he was proud.

When I started my next investigative story, Mike had only one question for me: How come I wasn’t pursuing something as exciting a subject as the University of Michigan?