In March 2001, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s main conference hall buzzed with Washington lobbyists. They were there to hear a speech by Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham—the first public preview of the Bush administration’s national energy strategy. For these powerful energy lobbyists, the speech confirmed that the White House was delivering on its promise to make life easier for the coal, natural gas, oil and nuclear power industries in the United States. As journalists later learned, some of those business representatives had privately met with White House officials and had helped shape the strategy.

As an energy reporter jammed in the back of the room, shoulder-to-shoulder with dozens of other scribes and TV crews, the event was an “ah-ha” moment. The enthused reaction of the inside-the-beltway crowd and the pro-industry language in the speech signaled the emergence of a new era of federal energy policy. In fact, energy issues have served as a significant subplot in the war-dominated chronicle of the Bush administration. Long before President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney stepped into the West Wing, the two had served as energy industry executives and were sympathetic to the energy industry arguments. Since taking office, they have included energy issues in their decision-making on a variety of military, political and environmental matters.

Energy, economics and environmental policy have long been inextricably intertwined. At least that’s how a National Journal editor explained it to me in the late 1980’s when he talked me into adding the magazine’s energy portfolio to my environmental beat. The late Dick Corrigan, who had written about energy and environment for The Washington Post and the National Journal, made me a promise. If I could stomach dealing with BTU’s and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, my job would never be dull. It’s an assessment with which I wholeheartedly agree.

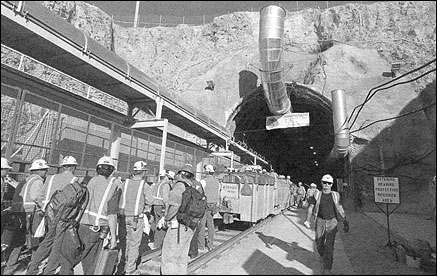

The Yucca Mountain Project, Nevada. Photo by Laura Rauch/The Associated Press.

Politics and Energy

In some ways, covering the Bush administration’s energy policy began with the 2000 presidential race. Political pundits noted that Bush carried West Virginia, usually a Democratic stronghold, by promising to support the state’s coal industry. In fact the Bush/Cheney ticket, which vowed to champion the interests of the extraction industries, did well in most energy producing states in the South and Rocky Mountain West.

But it became clear how much energy would win out, especially over environmental policy, once the administration’s 2001 energy policy report was released. Among other things, it spelled out plans to expand oil and gas development on millions of acres of federal lands, including wild regions that had been protected by the Clinton administration. It also confirmed the administration’s intention to ease environmental controls on older coal-fired power plants.

Congressional Republicans have incorporated many of Bush’s energy proposals into their omnibus energy packages, which have included billions of dollars in energy-related tax incentives, two-thirds of which would go to the fossil fuel and nuclear power industries. But for the past three years, that legislation has been entangled in political wrangling in the Senate and recently raised new deficit-reduction concerns at the White House. Instead of waiting for Congress, Bush has made significant headway in reshaping national energy policy by working under the public radar screen, reinterpreting and rewriting the little-noticed federal land-use and environmental protection regulations in the name of energy development.

Many of the administration’s energy maneuvers have been complex, technical and almost impossible to track. But from a policy wonk’s perspective, a few have been fascinating. Take the administration’s efforts to resurrect nuclear power. During the 2000 presidential campaign in Nevada, the Republicans won the state by promising that Bush would never use Nevada’s Yucca Mountain as a permanent dump for the radioactive waste piling up at the nation’s 110 commercial nuclear power plants—unless the proposal was based on the “best scientific evidence.” But Bush officials knew that to lure potential investors into sinking money into building new nuclear power plants, the government had to solve the waste problem. Once in office, the President took immediate steps to speed approval of the Yucca project. Bush signed off on the Yucca facility in 2002, leaving continued questions about the long-term safety of the site to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Now several electricity companies are rallying around a plan to order the first new nuclear plant in the United States since the 1979 Three Mile Island power plant meltdown. Where will they build the facility? That industry consortium is apparently eyeing a site owned by the Tennessee Valley Authority, a quasi-federal corporation. The potential investors are also hinting that they will need hefty federal financial incentives to build the new plant.

Headlines about energy have changed since Abraham’s 2001 speech, when California was suffering from rolling blackouts and the Western states were hit by historically high electricity and natural gas prices. Back then, politicians and consumer groups were beginning to cast a suspicious eye at energy wheeler-dealers like Enron and Reliant Energy. Meanwhile, car owners filling up at the pump were witnessing the signs of summer gasoline price volatility. Since then, California’s energy crisis and the resulting economic downturn triggered, in part, the ouster of Democratic Governor Gray Davis and the election of the high-profile Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Energy trading scandals brought down Enron and resulted in huge fines against Reliant and other companies. Western electricity prices have stabilized. But high natural gas and gasoline prices continue to plague consumers across the nation.

Energy Stories to Watch

What happens next? No matter who is elected President this fall, a handful of energy stories are certain to remain on my watch list. Those issues include:

- Climate change: In 2001, Bush withdrew the United States from the United Nation’s Kyoto Protocol to control climate change. That treaty would have required the United States to dramatically cut its emissions of carbon dioxide and other pollutants that scientists have linked to global warming. Oil-burning cars and coal-burning power plants and boilers are among the worst emitters of greenhouse gases. Nonetheless, the European Union in 2005 will begin an unprecedented emission trading program that will allow companies to buy or sell credits as a way of reducing their greenhouse gas emissions. Most U.S. companies can’t participate. The Kyoto treaty will become legally binding once it is ratified by Russia—a step that is guaranteed to increase international pressure on Bush.

- Electricity demand: By 2025, the nation is expected to use 40 percent more electricity than it used in 2002. Will it be reliable? Where will it come from? In the last decade, natural gas has been the favored fuel. But in the wake of high natural gas prices, some power companies are taking a new look at coal. Nuclear proponents say the nation can cut pollution and fulfill its power needs with new nuclear plants. Meanwhile, wind, solar and other renewable energy companies are waiting in the wings, hoping for new technology leaps, federal subsidies, or environmental regulations that could kick their industries into the big leagues.

- Oil: The United States has only three percent of the world’s oil reserves, but uses 24 percent of the world’s annual oil output. Even if the Bush administration convinces Congress to open Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil exploration, the new output probably won’t impact world oil prices. Bush has no plans to significantly boost federal fuel economy standards. Meanwhile, Americans are paying the highest recorded price for gasoline. Oil has also become a foreign policy story.

- Electricity restructuring: For decades, electric companies were state-regulated monopolies. In recent years, several states have allowed independent electricity generators to sell energy directly to consumers. The change has been part of a revolutionary and currently incomplete transformation of the way the electric industry operates and is regulated. California’s failed attempt at deregulation, for example, resulted in skyrocketing energy prices. Battles raging between the states that have opened their markets to competition and those that oppose such changes make this story one of the most complex, geeky and absorbing energy issues to watch.

Energy issues rarely make for sexy stories. They only draw front-page play during an energy crisis. And they are often so technical that they defy translation into plain English. But energy is the lifeblood of the economy. In our industrialized economy, electricity and transportation have become nearly as important to Americans as the air they breathe. As a result, energy will always be a hot topic with Washington policymakers and a fascinating beat for Washington reporters.

Margaret Kriz covers energy and environmental issues for the National Journal and writes a column for The Environmental Law Institute’s magazine, the Environmental Forum.