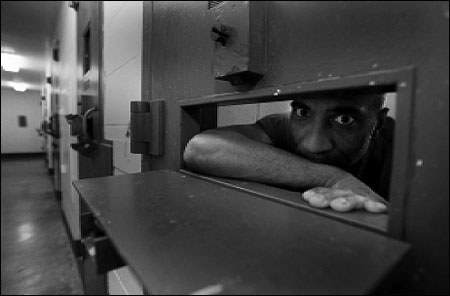

Bernon Howery, sentenced to death for the murder of four children, three of whom were his, in a 1989 house fire, is being held at the Kankakee Detention Center. Photo by Heather Stone, courtesy of the Chicago Tribune.

On January 31, 2000, Illinois Governor George Ryan took the historic step of declaring a moratorium on executions, making Illinois the first state to suspend the march of condemned inmates to the death chamber. The announcement by Ryan, a Republican who supports the death penalty in principle, resounded throughout this nation and the world.

At the Coliseum in Rome, golden lights flickered on and burned through the night in celebration. In Washington, President Clinton praised Ryan’s courage, while members of Congress proposed a moratorium on federal executions. The New Hampshire legislature voted to abolish the death penalty, although that measure was vetoed. Governors in Indiana and Maryland ordered studies of their own systems of capital punishment. In Virginia, Christian Coalition founder Pat Robertson expressed doubts about the death penalty. So did conservative columnist George Will and a variety of other unexpected voices. New polls showed significant declines in capital punishment’s public support.

In Chicago, where Ryan made his announcement before a thicket of microphones and cameras, the moratorium provided an exclamation point to a five-part series that ran in the Chicago Tribune two months before. The series, published in November 1999 following an eight-month investigation, detailed the failure of the death penalty in Illinois. Fellow reporter Steve Mills and I attended the press conference and had the unusual experience of hearing the governor recite statistics from our series, including our findings on the high number of sanctioned defense attorneys and the prevalent use of jailhouse-informant testimony in capital cases. In describing the need for a moratorium, Ryan cited the Tribune’s findings and the state’s abysmal track record of exonerating more death row inmates than it has executed. For Steve and me, Ryan’s announcement helped validate our approach to reporting on criminal justice issues and reaffirmed that “the power of the pen” is not a hollow cliché.

In three series that the paper published between January 1999 and June 2000, the Tribune tackled the subject of wrongful convictions, determined to learn why our nation’s courts repeatedly convict innocent people, and even condemn them to die. The trilogy consisted of investigations focusing on misconduct by prosecutors, the death penalty in Illinois, and the death penalty in Texas.

Our goal was to move beyond the kind of anecdotal reporting that so often defines the media’s coverage of criminal justice issues. An in-depth account of a single case can certainly make for a gripping story. But stranded without context, these isolated miscarriages of justice can be, and often are, dismissed as mere aberrations. A comprehensive approach, one that quantifies those elements that regularly contribute to cases of wrongful conviction, assumes a power and significance that reporting on a single case simply cannot acquire.

In our investigation of the death penalty in Illinois, we examined all 285 cases in which a person had been sentenced to death since Illinois reinstated capital punishment in 1977. Our reporting included reviewing Illinois Supreme Court and federal court rulings, appellate briefs, trial transcripts, trial exhibits, affidavits and other supporting materials used on appeal. That research helped us isolate particularly compelling examples of justice gone awry while also uncovering how certain fault lines run through dozens or even scores of capital cases.

Here is some of what we learned by meticulously working our way back through these court records.

- At least 33 times, a defendant sentenced to die was represented at trial by an attorney who has been disbarred or suspended, sanctions reserved for conduct so incompetent, unethical or even criminal the lawyer’s license is taken away. In one case, a judge appointed an attorney to defend a man’s life a mere 10 days after the attorney got his law license back. The attorney had just served a nine-month suspension for failing a string of clients through incompetence and dishonesty.

- At least 35 times, a defendant sent to death row was black and the jury that determined guilt or sentence was all white. This is a racial composition that prosecutors consider such an advantage that they have removed as many as 20 African-Americans from a single trial’s jury pool to achieve it. Of the 65 death penalty cases in Illinois with a black defendant and a white victim, the jury was all white in 21 of them, or in nearly a third.

- In at least 46 cases in which a defendant was sentenced to die, the prosecution’s evidence included a jailhouse informant. Such witnesses have proved so unreliable that some states have begun warning jurors to treat them with special skepticism.

- In at least 20 cases in which a defendant was sentenced to die, the prosecution’s evidence included a crime lab employee’s visual comparison of hairs. This type of forensic evidence dates to the 19th century and has proved so notoriously imprecise that its use is now restricted in some jurisdictions outside Illinois.

- Errors by judges, ineptitude by defense attorneys, and prosecutorial misconduct have been so widespread in Illinois death penalty cases that a new trial or sentencing hearing has been ordered in 49 percent of those cases that have completed at least one round of appeals.

A couple of weeks before Governor Ryan declared a moratorium on executions, Cook County prosecutors dropped charges against Steve Manning, an inmate whose case we investigated in our series while exploring the corrosive effect of jailhouse-informant testimony. That made Manning the 13th Illinois death row inmate to be cleared. This is one more than the state’s total number of executed inmates since the death penalty was reinstated. Manning and his attorney credited the Tribune’s investigation with his exoneration.

After Ryan suspended executions in Illinois, Texas Governor George W. Bush said he saw no reason for his state—the nation’s busiest executioner—to follow Illinois’ lead. Bush, the Republican candidate for President, expressed unwavering confidence in the fairness and accuracy of his state’s system of capital punishment. That statement prompted Steve and me, along with a third reporter, Douglas Holt, to head to Texas and apply our systemic approach to death penalty cases there. We examined 131 cases in which an inmate had been executed while Bush has been governor. Four months of investigative reporting produced some stunning results.

- In 43 cases, or nearly one-third, a defendant was represented at trial or on initial appeal by an attorney who has been publicly sanctioned for misconduct.

- In 40 cases, defense attorneys presented no evidence whatsoever or only one witness during the trial’s sentencing phase. In at least 29 cases, the prosecution presented a type of dubious psychiatric evidence that the American Psychiatric Association has condemned as unethical and untrustworthy. We also found that jailhouse-informant testimony and hair-comparison evidence are just as prevalent in Texas as Illinois.

- Working on these three series has left me with some reflections about the role journalists can play in examining contemporary social issues. History doesn’t belong to historians alone. Journalism is not history’s first rough draft and nothing more, as some people contend. We are allowed to do subsequent drafts, too. In the Tribune’s series on prosecutorial misconduct, we examined cases going back to 1963. In our series on the Illinois death penalty, we went back to 1977. Stories don’t lose their importance or impact by reaching back in time. Besides, the kinds of systematic problems that we isolated in our reporting plagued our courts then and continue to do so now. That continuum shows how deeply ingrained such problems are.

Statistics can resonate. In a time when anecdotal leads dominate news pages and the emphasis is often on using a single event, person or case to illuminate a larger story, we sometimes forget that numbers hold power. In announcing the moratorium on executions in Illinois, Governor Ryan relied on statistics, not individual stories.

In writing about the criminal justice system, issues of fairness should not be discounted as legal esoterica. We sell readers, listeners and viewers short when we assume they care only about questions of a person’s innocence. The Tribune’s findings on the shortcomings of sentencing hearings in Texas’ capital cases said nothing about innocence or guilt, but spoke volumes about the system’s fairness.

Those findings, and many others, reverberate among our readers and in other media accounts of our series. Too often, journalists don’t pay heed to what’s going on in our midst. We simply miss the big picture. For example, the number of exonerated inmates has climbed dramatically in recent years, thanks largely to the emergence of DNA testing and its role in exposing wrongful convictions. But for the most part, members of the media have covered each miscarriage of justice in isolation, bypassing the opportunity to learn from the mistakes common to them all.

Some stories deserve extraordinary commitment. The Tribune has expended an incredible amount of time and resources on the subject of wrongful convictions. Several reporters have worked on the story, and I’ve personally spent four years navigating electronic databases, conducting research in law libraries and sifting through hundreds of court files. It’s been money and time well spent.

Ken Armstrong is the Chicago Tribune’s legal affairs writer and is a 2001 Nieman Fellow.