Biddle, Bissinger, and Tulsky’s series on the Philadelphia court system documented an array of incompetence, politicking, and other transgressions, leading to federal and state investigations.

Behind the scenes, Common Pleas Court Judge George J. Ivins privately agrees to take a case from a defense lawyer who is a longtime friend—and then sentences the lawyer’s client, convicted of killing a young nurse in a car crash, to probation.

In another courtroom, on another day, Municipal Court Judge Joseph P. McCabe reduces bail for a murder defendant—without legal authority and without informing the prosecutor.

In yet another courtroom, Common Pleas Court Judge Lisa A. Richette sentences a convicted killer to prison—and then, after the victim’s gratified family has left the scene, changes the sentence to probation.

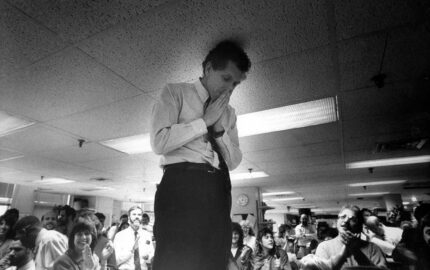

In a fourth courtroom, Municipal Court Judge Arthur S. Kafrissen gets up from the bench at 10:45 a.m. and walks out for the day, leaving behind baffled witnesses, police officers and lawyers. In the words of Clifford Williams, a disgusted witness, it was “complete chaos.”

Day by day, this is the Philadelphia court system, where many judges and lawyers freely admit that, all too often, what is delivered is anything but justice.

It is a system in which many defense lawyers help finance judges’ campaigns—and then try criminal cases before those judges. It is a system in which those same lawyers have remarkable success, with statistics showing that in Municipal Court, from 1979 to 1984, defense lawyers who had a role in judges’ campaigns won 71 percent of their cases before those judges. By contrast, during the same years, only 35 percent of all Municipal Court defendants won their cases.

It is a system in which witnesses are sent to the wrong places by incorrect subpoenas, and in which a judge dismisses a case because a witness isn’t in the right courtroom.

It is a system in which defense lawyers get convictions overturned on the ground of their own incompetence by claiming they made errors that would shock a first-year law student.

It is a system in which the amount of money awarded in civil verdicts has skyrocketed and in which a person can win $143,500 for a broken toe suffered on the job.

It is a system in which hallways smell of urine, benches are carved with graffiti and stairways are missing railings.

And it is a system in which many judges feel overwhelmed, bereft of hope for improvement and wistful for other employment.