Curiosity should be the first trait that newspaper editors screen for when they consider reporter applicants.

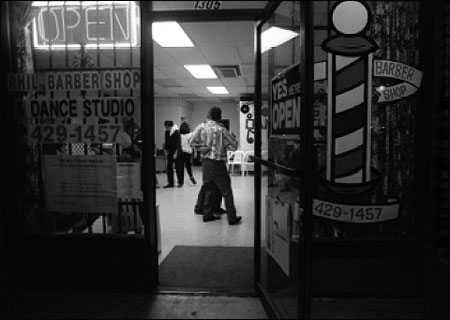

A curious reporter stops for coffee and notices a small sign in the window of the barbershop next door. She learns that the barber transforms his shop into a dance studio at night and teaches ballroom dancing. She writes a cover story that runs with great photos.

A curious reporter doesn’t wait for the city to deliver its agenda each week. She makes contacts within city hall and among active residents, allowing her to know weeks ahead of time what community issues will come before the council. When she writes about an upcoming meeting, it’s more than just inside filler, it’s a cover story with great photos.

Curious reporters are not satisfied with what government officials and civic leaders place before them. Curious reporters always look beyond the official record for the rest of the story—the best story.

Curious reporters who also possess good writing skills don’t need any other tools or gimmicks or direction. Turn them loose in a given geographic area and, without prompting, they tell that community’s story—not just from government’s perspective but from the perspective of the people who live and work there.

And curious reporters are the future of our franchise.

Our readers have many other options when they want news. Radio and television remain formidable foes for breaking news. News and entertainment Web sites offer an immediacy and specialization that newspapers struggle to match.

Our future rests in our ability to cover communities. We need to learn how to do it better before some upstart dot-com takes the franchise away.

If our newsrooms were filled with curious reporters, we wouldn’t have to agonize over how to better cover communities, how to reach into diverse neighborhoods, how to best document all the demographics of our regions. But the reality is that our newsrooms, at best, are only half full of curious reporters.

For everyone else, there’s civic mapping (or tapping).

It’s impossible to teach curiosity, but you can teach a reporter how to end what I call “agenda addiction” and find community stories that go beyond government.

Civic mapping is simply a tool that encourages good journalism. It offers steps that prompt reporters to ask the questions that come naturally to their curious colleagues. It suggests a pathway to real people that begins with civic leaders—with whom most reporters are comfortable—but leads to the more ambiguous world of active residents and neighborhood leaders, the place where most good community stories originate. I view civic mapping as an efficient way to quickly learn more about a community, an issue, or people with shared interests.

One premise of civic mapping is that there are many layers to community, but journalists tend to spend time only in the top and bottom layers. We attend civic meetings, and we go into people’s living rooms—usually when tragedy occurs. But we don’t tell many of the stories that percolate in the layers between. By learning to report in those in-between layers, reporters can find stories before they reach an agenda. They can discover the people in any given community whom others turn to for information.

At The San Diego Union-Tribune, we first used civic mapping to get to know the community of Eastlake, a large, new housing development within the city of Chula Vista. One of the most surprising things we learned was that many of the residents viewed the Vons supermarket—a large chain store—as a place to go to find out what was going on in their community. It was the only grocery store in the area, so residents almost always ran into someone they knew there. It was, in effect, their town square. And the astute store manager capitalized on this.

He made a point to post notices of all the upcoming community and neighborhood events. Residents knew they could go there and find out what was going on. Another surprising finding about Eastlake was that city hall is the last place residents turn for help. They turn first to their homeowner’s association, next to a woman named Natasha who works for the developer and also lives in the development, and finally to the developer. The story of that leadership structure became a centerpiece package for us.

Two important stories in our area had been covered exclusively at the official level. One was a proposal to develop a cargo airport at Brown Field, a municipal airport. The other was a proposal to build a toll road that would ease traffic in this rapidly growing suburban area. But this would not happen without making some neighborhoods much less inviting. By covering these issues only at that layer, we were really only covering the approval process, not the community. In the instance of Brown Field, there were many issues we missed by our limited focus, and once we began talking to residents, they let us know clearly that we had missed a story they considered very important. We attempted to remedy that. The result was a rich Sunday package that has continued to pay dividends. We still hear from the people whose lives and businesses will be affected by this airport. In the case of the toll road, we had missed a strong community story about the people whose neighborhoods would change in order for more recent residents to have better freeway access. We had told the story at the public hearing level, but never at the community level until we spent time in the neighborhoods—away from the meetings.

Another premise of civic mapping is that journalists do not listen well. We ask our questions and then listen for the best quote. Once we have that sound bite (and print journalists are as guilty of this as broadcast), we move on to our next question without necessarily hearing or considering what else our subject has to say. In National City, one of the gathering places is the Senior Nutrition Center. We know this is a good place to find seniors, and the crowd is diverse. We have dropped in to gather quotes on senior issues and the presidential recount, but it had been more than 10 years since we told the story of the center. When a reporter decided to check out a news release that the center was adding breakfast, she saw this dining room as a community unto itself and told its story. What might have been a brief became a centerpiece package.

Yet another premise of civic mapping is that journalists go into stories with preconceived notions that we are sometimes reluctant to abandon. During a recent Chula Vista City Council race, some candidates made a point of mentioning an area of town they viewed as neglected. They pledged their support to improving services to the downtrodden neighborhood. After the election, both the reporter who covered the primary and another who covered the runoff proposed doing a more in-depth story looking at this neighborhood. Both offered the premise, which they drew from the campaign, that the area, annexed 15 years ago, did not have sidewalks or other basic city services and residents were tired of being ignored. When the story appeared in the newspaper, it had a very different tone. And residents were pleased with the attention they had gotten from the city. They still have work they want the city to do, but they view a new recreation center and a new library nearby as tangible commitments by the city to the area. Our story reflected residents’ opinions, not the candidates’ views.

By reporting in many community layers, by listening to what residents say is important to them, by abandoning preconceived notions, reporters can turn routine events into rich stories of community life. Two reporters did just that with “A Centro for San Ysidro,” a story that could have been just another ribbon-cutting brief. Instead, here was the opening of the main story:

SAN YSIDRO—Merchants along San Ysidro Boulevard have traditionally promoted their businesses with events in downtown San Diego or Coronado. Miss San Ysidro is typically selected at a pageant in Chula Vista. The thriving music, theater and dance program at San Ysidro Middle School holds its annual spring show at Eastlake High School. In a school district where many parents don’t have a car, it’s been an inconvenience to have eighth-grade promotion ceremonies at Southwest High School in Nestor, “where our children are so far from where they should be,” said San Ysidro parent Alicia Jimenez.

In a community where there is no civic center, no country club, no hotel ballroom, there’s been no place to celebrate San Ysidro. Five years ago, the people made a school bond wish list, and they asked firmly and repeatedly for a community auditorium. Today they get it.

At The San Diego Union-Tribune, we have used civic mapping in limited ways during the past year to learn more about southern San Diego County. During a lengthy press expansion, South County did not have a zoned edition, but we were still able to apply this reporting philosophy. The results, despite our limitations, have substantially improved our community coverage. This year, with the return of a South County edition, we will apply civic mapping more deliberately and hope for even greater results.

So, what about the “map?”

Richard Harwood, who teaches this method, isn’t going to like this answer. Ideally, the information gathered through civic mapping will be shared with other journalists. This can be as simple as an extensive source list that provides detailed context for each name on the list. It can be as elaborate as an Intranet Web site that reporters in the newsroom can access whenever they have a need to report in a given community.

The reality is that the maps are difficult to maintain. Unless you have someone who can devote time each week to maintain a Web site, it will be difficult to create maps that benefit the entire newsroom. Even with source lists, reporters tend to keep their source information to themselves. They are often happy to share when other reporters seek their expertise, but information is power, and this information helps them do their jobs better than anyone else. Why would journalists want to give it away?

In many ways, the map becomes the community stories you write using civic mapping. These stories help journalists and their readers gain a better understanding of the communities where they live and work.

Karen Lin Clark is South County editor at The San Diego Union-Tribune, where she has worked for 11 years. For five of those years, she created and directed the newspaper’s “Solutions” project, finding and telling stories of community struggles and successes. She previously worked as night city editor of the Dallas Times Herald and as an education writer at the Hayward (Calif.) Daily Review.