In late March, I had to make a choice. I was stuck in Cizre, Turkey, hoping to get into Iraq to cover the war. Syria and Iran had closed the borders. Turkey had closed its borders weeks before. Should I try to sneak into a war zone by boating across the Tigris near the Syrian-Turkish-Iraqi border? Or should I pay $3,000 and take the smugglers’ route across the Turkish border, through snow-draped mountains and Turkish snipers accompanied by three guys with AK-47’s?

I took the mountainous route, and readers of Back-to-Iraq.com, the Web site that I started last year, were able to read all this, practically as it happened, thanks to a revolution in technology and a lack of sanity on my part.

But perhaps I should back up a bit. In the fall of 2002, I started a Web site using off-the-shelf blogging software. I had returned to New York from northern Iraq, where I did some freelance reporting, but I was having a hard time selling my stories. I was frustrated with editors who seemed to care little about the Kurds who live in this region of Iraq. Or perhaps the market was simply glutted after several stories had been published that spring.

Based on my reporting experiences, I started writing stories for my Web site. At about the same time, I came across SaveKaryn.com, a scheme by erstwhile spendthrift Karyn Bosnak to erase her credit card debt by asking strangers for money over the Web. She had become a minor cause célèbre and eventually raised about $13,000.

Blogging From Iraq

I decided to try my hand at “blograising.” Instead of offering warm appreciation to the donors, as Karyn did, what I could offer were first-hand accounts of life in Iraq. And with funding from readers, when war on Iraq was declared, as I presumed it would be, I planned to report on that for the donors using a premium e-mail list to distribute copy and pictures. With this plan, my Weblog, www.Back-to-Iraq.com, was born.

By the time the bombs dropped on March 20, I had raised $8,000. Within the next few days, another $2,000 was contributed, and I bought my ticket to Istanbul. I planned to travel to Ankara, meet up with John Courtney, an ex-Marine who had discovered Back-to-Iraq while he was waiting in Turkey, also looking for a way to get into Iraq. Together we would somehow make our way into the country.

Using a borrowed laptop and a rented satellite phone, my plan was to send back stories and pictures. There would be no editors, no advertisers, no strings attached. I’d have to rely on the training I had from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism and the experience from when I’d worked as an international editor and national writer at The Associated Press and apply this to the blog. But now I had the freedom to report and write what I witnessed and experienced. It also meant that I had no backup should things go wrong.

This brings me back to the decision I had to make in March. Either I figure out how to get into a war zone or go home. But going home no longer seemed like an option since I had more than 320 donors to my Weblog, donors who would eventually give more than $14,000 to get me to Iraq so that I could report on the war as an “independent journalist.” By then there were also about 25,000 daily readers of B2I, as my Weblog came to be called, and posting comments and suggestions. Instead of having one editor, I had thousands. And they wanted me there.

This was journalism without a net, on the Net, and it had never been done quite like this before.

But was what I was doing journalism? I had no official press credentials, only my reporting experiences in the region from the previous year. Nor did I have any major media outlet behind me with which to impress either sources or other journalists. And with no editor to guide my story selection or to read my words before they were published to a worldwide audience, there was no one to offer me story advice or curb my rhetorical excesses.

Yet I believe that B2I is an example of journalism. It was about a guy with a notebook asking questions and then telling people the answers to his questions. It was about bringing the stories I saw and heard to people interested in reading them from a corner of the world (the northern front prior to the fall of Baghdad and Tikrit) that wasn’t widely reported on. And my reporting was done without any outside pressure being applied, the kind that sometimes can bias what gets reported. My reporting created a connection between the readers and me, and they trusted me to bring them an unfettered view of what I was seeing and hearing.

Readers Respond to His Reporting

When I asked readers why they supported B2I, Lynn McQueary responded: “Back-to-Iraq definitely brought stories that the mainstream media didn’t. As an independent journalist, you didn’t have to work within the confines of what would be ‘acceptable’ to print.” Trish Lewis liked that I had “the independence it gave you the reporter. No agendas except your own, which is perfectly acceptable to me. No one is totally objective. But you were free to do what you wanted. Also, you gave more personal perspectives of ‘behind the scenes’ of what it takes to do what you do, which was terribly fascinating to me.”

Once the idea sunk in that readers like these women were my actual editors, interesting things happened. So that readers would know where I was, prior to beginning the two-day trek across the mountainous border between Turkey and Iraq, I filed from a meadow 10 miles from the Iraqi border. In that story, I sent this cliff-hanging close, “We’re leaving in 15 minutes. When next I write, I should be back in Iraq.”

Later, after I referred to my mountain journey as being “like a Bataan Death March,” I gave a very public mea culpa. Some of my readers had lost relatives on that much more hellish journey and had complained on the site’s public comment section about my choice of words.

Because many readers asked about the Turcoman people who live in Iraqi Kurdistan and Kirkuk, I did a story about them, explaining some of the ethnic politics of the region and how the Turcoman people were attempting to drag Turkey into the powder keg so they might get a shot at Kirkuk’s oil revenue. I never saw another story about the Turcoman’s role, so I was glad that my readers led me to doing this story. Over time, I started reporting in a more focused manner, as I worked to fulfill specific reader requests while still also relying on my own instinct for news.

Through it all, I maintained a personal tone in my writing as I tried to let people know what it felt like to be working and surviving during such an extraordinary event. My antiwar stance had been well-known to anyone who had read B2I before I left for Iraq, yet once I was there I reported what I witnessed as straight down the middle as I could. When a crowd of Kurds shouted how glad they were that the war had started, I reported it as they said it. When they told me how much they liked Fox News because “Fox News is true!,” I reported that, too.

When I wasn’t able to get a direct source on a story, I didn’t write it. And I kept my commentary to a minimum while I was in Iraq; readers already knew my opinions, so they didn’t need to hear them repeatedly. I strongly believe that if blogs are ever going to be taken seriously as a journalistic medium, their authors will have to be as conscientious in their reporting conduct as any mainstream outlet.

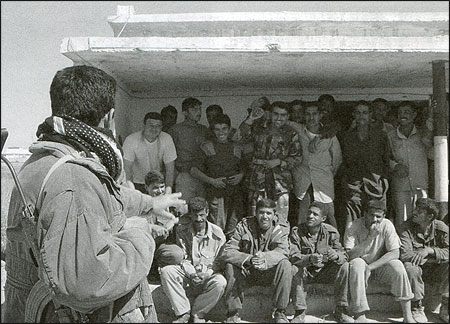

On the day Kirkuk fell to the Kurds, hundreds of Iraqi conscripts surrendered. A group of POW’s and their Kurdish guard pose for pictures before being sent to Arbil for processing. Photo by ® 2003 Christopher Allbritton.

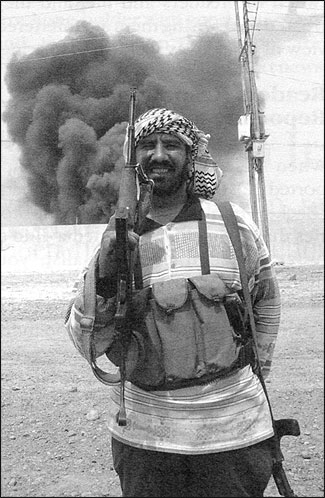

An Arab fighter in Tikrit poses for a picture while a factory burns in the background. Tikrit had mostly fallen to the Americans, but still many armed factions roamed the city. Photo by ® 2003 Christopher Allbritton.

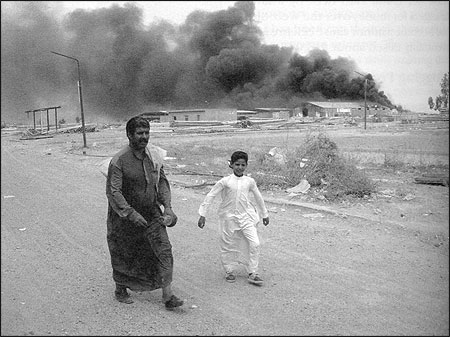

A father and son flee a burning factory after Kurds—or U.S. attacks—set it on fire. Photo by ® 2003 Christopher Allbritton.

Weblogs and Journalism

None of this should suggest that Weblogs will replace The New York Times. Instead, blogs should be the seasoning—or maybe the garnish—in a reader’s well-balanced media diet. Their quirky, scrappy tone, their in-your-face opinions, and the personal scale of the publication are the main attractions of Weblogs. But none of those matter if the reporting is nonexistent or sloppy. I hope B2I showed that the qualities that make blogs unique and exciting can coexist with the standards of quality journalism.

This is an important goal if U.S. journalism is to reverse its crisis of credibility. For various reasons, a lot of Americans say they don’t trust their media. Weblogs written by those with some journalism training can renew that trust through the sense of personal connection that can be established through the interactivity of the medium. With this trusting relationship, bloggers can do good journalism. But with the chatty nature of the blogging medium, this trust and credibility can also be damaged. There is, however, the corrective power that derives from the medium’s interactivity. For example, during the war, when Sean-Paul Kelley of The Agonist, a well-known and wildly popular blog, was plagiarizing from Stratfor, a well-regarded military-intelligence newsletter, another blogger caught him and tipped off Wired.com, which eventually did a story on the scandal.

I started B2I not only to cover a war and advance my reporting career but also because I think complicated news stories benefit from having as many sets of eyes on them as possible. No news organization has a monopoly on truth, and independent journalists like me can pursue stories that mainstream journalists won’t cover. Because of my smaller and more focused audience and their interests, I told stories that revealed the humanity of a war zone, such as my story about stumbling into a village party in Taqtaq the night Baghdad fell and being mobbed by delirious Kurds so happy to see Americans in their midst.

Truth is elusive but it is always something more than merely a collection of facts. At times, it can be revealed through a mosaic of coverage that educates and enlightens readers. In my farewell note on B2I, I wrote: “While truth may be the first casualty in war, I hope I was able to save a small shard of it. But it’s hard to say. Many times since I’ve been here, listening to the claims of Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Turcoman or Assyrians, I’ve thought that there is no such thing as Truth, only myths that people tell their children to get them through to the next generation. History doesn’t exist here, at least not in the American sense. The past is never really past, and history isn’t something that happened long ago—it’s very much alive and kicking. In this ancient place, a land of empires, gods, gardens, wars, blood and beauty, at the heart of it, you will find only stories. I hope I’ve been able to bring a few of them home to you.”

Christopher Allbritton is a writer in New York and has written for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, The Associated Press, The (New York) Daily News, and various magazines and Web sites. He is working on a book about his experiences in Iraq and looking for funding (or an assignment) to cover another conflict.