As a kid, the first letter of the alphabet I learned was not A, B, or C. It was the letter F. A big fat red F with a circle around it.

As the first-generation son of immigrant Chinese parents growing up on New York’s impoverished Lower East Side, it was my own personal scarlet letter of failure.

At the age of five, I did not speak a word of English. I was the kid who didn’t raise his hand in class. Back then, the only superpower I wanted was to become invisible. Now, as I thumb through the old photos, I notice that I didn’t smile much back then.

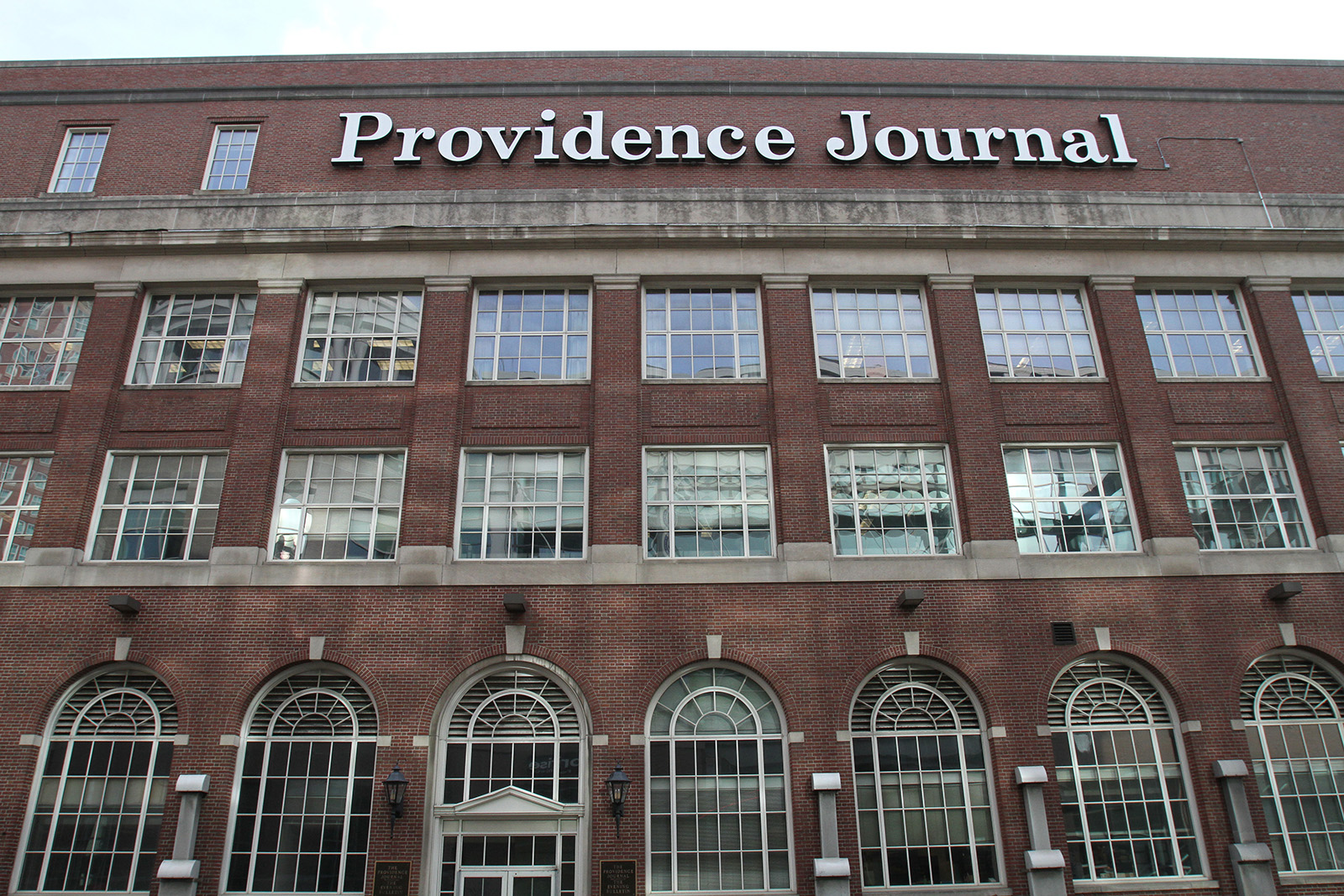

I thought of those days, those memories, and those images earlier this year when I was named executive editor of The Providence Journal.

The irony of the moment was not lost on me; that at another time in my life, albeit a distant past and one of fading childhood recollections, I would not have been able to read the very announcement of my own appointment. I would not have been able to read the words on this very screen.

My parents immigrated to the United States in 1957. I was born a year later. My mother came here with a suitcase in one hand and my older sister, barely a year old, in the other. On her first night in America, through the kindness of family friends, she slept on a living room couch. For months, it was her bed and my sister’s cradle. In time, my parents carved out a living, and we had a home in a cramped tenement apartment near Chinatown. Two years later, another sister would be added and the Ng family, five strong, would begin taking the wobbly steps toward the American dream.

In her infinite wisdom, my mother banned English from the home. Only Chinese was allowed. She knew that eventually we would learn English and that we would adopt and adapt. Mom knew it was inevitable that elements of the only life she knew would fall away, but in its place a new life would bloom from its roots, stretching to the other side of the world.

But for now, no English at home, only Chinese, so ruled my dowager mother.

On my first day of school, I sat at my desk, tone deaf to the classroom soundtrack of a teacher and her pupils. At dismissal, the teacher pressed a slip of paper into my hand and said, “Mother. For mother.” The next day, my mom accompanied me back to school.

“Mrs. Ng, your son doesn’t speak English,” the teacher said.

“I know,” my mother replied in thick-accented Chinese, slightly annoyed. “That why I send him to school!” The teacher would point to objects in the room, and I mouthed and repeated her words. “Blackboard.” “Book.” “Chalk.”

On January 21, 2021, my family history recorded two more words for the stories that will be handed down for our later generations: “executive editor.” That was the day the son of poor immigrant parents, a truck driver and nurse-turned-homemaker, was officially handed the reins of one of the nation’s most feisty newspapers.

Just as I was preparing to take over The Providence Journal, Kamala Harris became the first woman, the first Black, and first Asian American sworn in as

U.S. vice president. I believe that with this shift in history, a new style of leadership will also emerge, a style rooted in the ability to bring people together.

To be a journalist is more than making entries into our national diary. It is, I believe, to tell the stories that bring us together; to find the common threads in all our lives that bind us to a common purpose, and not act as some glorified scorekeeper tracking winners and losers on a public stage.

And now, more than ever, leading any news organization means ensuring a voice for the many who have often gone unheard, unnoticed, or ignored. We also cannot demonize those with whom we disagree.

As journalists, I believe our greatest tool is telling the stories that bind us, that connect the dots. I have often said that my story is our story — be you Black or Asian or white; male, female or nonbinary; rich or poor; young or old; liberal or conservative. In the collective narrative that is our nation, we all have at times believed we were invisible to others, deemed less worthy. We all took turns wearing our own cultural or political scarlet letter as outcasts. Some of us still do.

In the 1800s, as the Irish fled their ancestral home and as the famine killed an estimated one million people, they landed in the northeast corner of this country, praying for hope and survival. In time, the Irish dared asked for equality. A newspaper of great repute at the time accused the Irish of being agents of the Catholic Church and that they neither deserved equality nor sanctuary within the state.

That paper? The Providence Journal.

This story is literally inscribed in stone in a memorial dedicated to the “Great Irish Famine of 1845-1851.” It sits along the banks of the Providence River, less than a five-minute walk from my new home.

Our best and only gift is to tell the stories that help connect the dots. You might even call that providence.

David Ng is executive editor of The Providence Journal. He is a former executive editor of the Daily News in New York. He also served as associate managing editor at the New York Post, senior news editor at Newsday on Long Island and assistant managing editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey.