Journalist Ash Sweeting rides in a pickup with the Afghanistan National Police. Photo by ©Travis Beard/Argusphotography.

Nothing has more power to communicate the destruction and despair of our time—especially from the war zones of Iraq and Afghanistan—than photography. But in the sanitized and censored environments now of government and military control, taking the picture can be as difficult as getting it published.

In coverage of these wars, freelance photojournalists are indispensible. One after another, news organizations have abandoned the task of informing the public. For editors back home, photojournalists—and the images they transmit—are problematic. But it’s not the photographers who pose the problem; it’s the truth their images tell. During the Vietnam War, there was the searing image of nine-year-old Kim Phouc running down the road with her flesh melting and fusing into her body after a napalm strike and her brother running in front of her with an expression that recalled Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” This photograph spoke to people in ways that words had failed to do. These children were ones the Americans were supposed to be saving, not bombing. Images such as this one did much to turn the tide of that war, but if they did, it was because they conveyed important truths.

Press Restrictions in Afghanistan

Most of the freelance photographers who once worked in Iraq have moved across to Afghanistan and now feel compelled to tell the story of this country and its people—the 30 years of war it has sustained, with billions of dollars spent on weapons and aid. In the eight years since America and its allies arrived to oust the Taliban, little seems to have changed except for the presence now of suicide bombers.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, those who control the battlefields require a compliant media and so embedding (or in-bedding as some call it) is seen as a way to manage reporters and photographers while appearing to provide access. But the not-so-well hidden agenda underlying it is that by being assigned to a particular unit it creates what the military calls “unit cohesion” or bonding among fellow human beings who spend time together in dangerous situations. Loyalties and empathies surface as journalistic objectivity can disappear.

But not every reporter and photographer in Afghanistan is towing the official line, even as military restrictions on the press are increasing as the war intensifies. To function in Afghanistan, a member of the press must have media accreditation, issued by NATO’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) headquarters in Kabul. ISAF now demands that applicants take a Biometric Automated Toolset (BAT) examination; the results—which include highly personal information—are kept by the U.S. military for the apparent reason of facilitating entry to all military bases in Afghanistan for accredited press. ISAF doesn’t provide a privacy guarantee.

I have been living in Afghanistan for more than two years and recently had to take a BAT test. When I asked whether “the data will be shared with any other parties outside the ISAF media office,” they refused to answer. I asked the officer in charge why this security procedure had been introduced. His answer: “Too many Afghans are getting access to the base, so we’ve introduced this system to filter out the supposed journalists from the real journalists.”

Journalists use the embed program to get to the war’s frontline. Most other aspects of reporting can be done without “help” from ISAF. My sense is that it can be more dangerous to be embedded since, when you move with military forces, you become a target. And chances of being involved in a suicide attack increase.

It is perhaps not surprising that similar to what is happening in Iraq, there is disparity in how Western reporters do their jobs (many opt for ISAF embeds) and how Afghans do theirs (traveling with Afghan forces and embedding with the Taliban). One reason for this could be that ISAF wants to make it difficult for Afghans to be able to embed with its forces for fear of sensitive information being compromised; the Afghans then choose the easier option of an Afghan forces embed. It could also be that Afghans are not embedding with international military units because many consider them to be a more dangerous option.

Though I’ve done embeds with ISAF forces for a story—and for the experience—I believe this approach to coverage is a contrived tool of propaganda. Now I try to report from a more independent perspective and use my extensive Afghan contacts to get the stories I think people throughout the world ought to see. My last embed was to a forward operation base in Zabul province, deep in Taliban country. The base was hit by Taliban mortar rounds on such a regular basis that soldiers joked about a 4 p.m. attack time. Sure enough, we were shelled by rounds from nearby mountains at just that time, so when I came back to Kabul I reported about the punctual assertiveness of the Taliban.

Months later I requested to return to the same base with ISAF. Numerous times I was told the base was not available to visit and was encouraged to visit other “less active” areas. Of the embedded journalists I talk with, most tell me that the time they spent with their unit was a little disappointing since they didn’t see enough action. Though some reports indicate that the Taliban now control up to 70 percent of the country, seldom do ISAF embeds get assigned to units in areas where those forces are losing ground. Usually they are sent to areas where ISAF is “winning” the war. Images of military action tend to come from journalists who were “lucky” enough to be in the right place at that time.

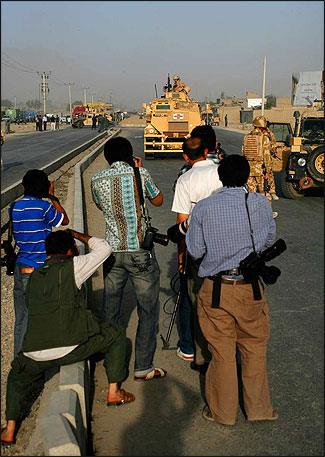

In 2007 the Taliban stepped up its campaign of suicide bombing in Kabul. The target then was often military convoys and international NGO vehicles. The casualties included innocent bystanders. After an attack the area was flooded by international and Afghan military, who kept the press at bay. Photo and caption by © Travis Beard/Argusphotography.

Clamping Down on the Press

The liberation of Afghanistan from Taliban rule created many new opportunities for Afghans, including the emergence of a youthful and energetic media industry. TV and radio stations—private and government run—started to broadcast, some funded by international donors. More than 300 newspapers are now in circulation throughout the country.

RELATED ARTICLE

Travis Beard wrote about Aïna Photo Agency and Afghan photographers it trained and displayed their work in a photo essay published. Read the article in the Spring 2007 issue of Nieman Reports »In a similar spirit, Aïna Photo Agency (APA), the nongovernmental organization where I work, was set up in 2002. There, Afghan photographers learn how to tell “through Afghan eyes” the truth of what is happening in their country. Years of absence of a free press explain much about the years of conflict that Afghans have endured. If a free press is essential to a democracy, then the work of APA’s graduates will be part of its bedrock.

In our early years, these Afghan photojournalists were met with open arms and support from the Afghan government and international donors. But as time has gone by—and with the Iraq experience informing the situation here—the Afghan press started to strongly question the effectiveness of eight years of occupation by the allies. When the press started to feel empowered to show and tell the truth, it was only a matter of time before the military and government powers would retaliate.

Of course, during the rule of the Taliban it was more dangerous to carry a camera than a Kalashnikov; citing Islamic law, the Taliban declared it illegal to take or have images of living things. Being a photographer was not only brave, it was downright foolhardy as many were arrested, beaten and tortured. Their shops were shelled, their families persecuted, and sometimes they were killed just for taking a photograph or owning a camera. Fardin Waezi, now a professional photojournalist who trained at APA, was arrested seven times under Taliban rule for such offenses.

The ISAF seems to now be feeding on the Taliban’s paranoia about cameras. Signs banning the use of cameras began to proliferate at about the same time the Taliban seemed to be regaining a stronger foothold. Freelancers, like me, no longer hear people call out “Ax me Biggie,” which roughly translated is street talk for “take my picture.” The joy of traveling with a camera is turning into a misery on two fronts—with the military forces and now, too, on the street.

The Afghan government, guided by the United States, is also jailing journalists and even imposed a death sentence for student/journalist Sayed Parwez Kambakhsh2 Television stations have been raided. Newspapers closed down. Nor is there any assistance for Afghan journalists taken hostage by the Taliban. Their families must broker their release or they are left to die. It is not only more dangerous for Afghan journalists to operate here than it is for international reporters and photographers, but they get paid a lot less.

I see the situation for them worsening in 2009. What follows is an account of just one week of trying to function as a freelance photojournalist in Kabul.

.jpg)

British soldiers push photojournalists back from the site of a suicide blast. Photo by Fardin Waezi/Aïna Photo.

A Suicide Bombing in Kabul: At a suicide bombing on the Jalalabad Road, my colleague Fardin Waezi and I had an encounter with British troops, who were cordoning off the area. (Usually this is done by U.S. troops.) The Brits pushed the media back one kilometer from the blast site, but members of the press tried to inch closer. I challenged the soldier and asked him why we couldn’t get any closer to take some photos.

“Mate, I’m just doing my job securing the area and keeping you in a safe position.”

“I’m just doing my job, too, to report on what happened here,” I replied, to which he said, “It’s not you I am worried about; it’s the Afghan journos who are with you.”

“They are friends of mine and professional accredited photographers,” I told him.

“For all I know they could be the next threat,” he said, referring to the bombing.

This conversation went on for a while, and then the soldier became quite forceful and approached members of the press to move back. “Please don’t point your gun at me,” I said to him, and he told me he wasn’t. “I can see down the barrel of your gun, so you must be pointing it at me,” I said, and again he denied it.

It was only later that day when Waezi came to me and showed me his frames from the moment that it was clear that the soldier was pointing the gun at me.

Sign at the exit of the United Nations Humanitarian Air Services at the Kabul International Airport.

A sign in front of a military base says “no photographs.” Photos by ©Travis Beard/Argusphotography.

Photographing “No Photos”: I had a story idea of taking photos in places where the signs tell me I’m not allowed to be. Again, I took Waezi with me. We drove around Kabul requesting permission to take photos of signs saying “no photos.” We’d taken four such pictures without a problem when we went to the entrance of the President’s Palace and asked the Afghan guards if we could take a shot of their sign. They said sure, as long as we didn’t shoot any of the palace behind the sign. I reassured them we wouldn’t. We took the shot and said thank you. On the same street is Camp Eggers, a U.S. military base. We stopped to ask these Afghan guards if we could do the same. The guard in charge frowned, so we explained again what we wanted. Then he took our cameras and called for verification.

An armed U.S. soldier came out 15 minutes later and asked what we were doing. I told him. “I need to check this with my superior,” he said. In another 15 minutes a higher-ranking armed officer came out and asked us more questions. He asked for our IDs, made some radio checks for verification and our IDs were cleared, but then he confiscated our IDs and told us we could pick them up the next day. We were given back our cameras, and he then asked if he could take a photograph of us. I said, “Sure, if I can take a picture of you.” He declined, took the photo of us, and let us go. When we returned for our IDs, we were told we had to register again, and this was when I had my BAT test done.

Despite all of these security measures, there are moments when one must smile at how intentions sometimes go awry. On another occasion a friend and I went through full body scans, had our IDs checked, handed over our phones, and made our way to the restaurant at the NATO base in Kabul. We were somewhat surprised to find that she still had her passport. Turns out the security checkpoint had taken, by mistake, her address book.

Covering the Afghan story requires a deep understanding of the country’s people, its three-decade history of war, and the complex mesh of issues involved with this current conflict, including the roles played by Afghanistan’s powerful warlords, drug barons, and so-called “ministers” and the areas they control and why. With its labyrinth of regulations restricting press access, including that of Afghan journalists, government officials and the military are making it very difficult for eyewitness coverage to happen. The result can be seen in the all-too-common oversimplification of a complex story. And if roadblocks to coverage remain—and increase, as has been the case—the burgeoning Afghan media will gradually diminish in size and energy devoted to telling this story as realities of survival take over.

Travis Beard visited Afghanistan in 2001 as a photojournalist and then returned in 2006 as chief editor of Aïna Photojournalism Institute. There he has guided more than 30 Afghan students towards professional positions. He also works as a freelance photojournalist with Paris-based Picture Tank Agency and directs his own company, Argus Group, which offers services in translation, transport, security and logistics.