Years down the road, when I recall my first experiences as a journalist, one interview will stand out against all the others for its vividness. It was a rainy Friday night in a bar in a northern Montana town, and the person I was interviewing—a railroad conductor—asked me the first question: “Are you from France? You seem foreign.”

He was partially right. I was foreign to the place where I was that night, but not because I was from Europe. Rather, last spring I was working on a story about Native Americans for a special, in-depth publication produced by students at the University of Montana in Missoula. Although I had been in Havre, Montana, for a few days, and Missoula was just five hours away, this person accurately sensed that I was out of my element.

The assignment represented a time of many firsts for me—traveling to a new town to report a story and working as part of a reporter-photographer team covering Indian issues and interviewing someone in a bar. And as our conversation progressed, I quickly found out how difficult it was to prepare in the classroom for all that I was learning.

The conductor offered his perspective on the relationship between people who live in Havre and Native people who live about 25 miles away at the Rocky Boy’s Reservation. At one point he said, “Native Americans here are like the blacks in the south.” What spurred this comment was a tense moment in the bar, when four Indians walked through the bar and then abruptly left after a patron ridiculed them to his friends’ delight.

What I saw flustered me, but I finished my interview. As I did so, I tried to ask questions that would help me better understand this man’s life and perspective, but I was distracted by what I’d witnessed and my source’s reaction to it. When the photographer, Katie Hartley, with whom I was working, and I finally left the bar, we sat in her car for a few minutes in silence. Neither of us knew how to process what we had just experienced. We drove back to our hotel late that night, and I wrote for hours, trying to record what we’d seen and heard.

Professors warned us that our reporting assignment—with its focus on race—might seem overwhelming. And even though it was proving to be tough, I felt my teachers did a good job preparing us to cover people and issues with which we were generally unfamiliar. In our semester-long Native News class, seven photographers, seven reporters, and two designers learned as much as possible before being sent out to various locations to report. We became familiar with stories done by former classes, and guest speakers from newspapers in and out of the state came to give us reporting tips. Indian students from a local community college also met with us to offer their perspectives.

The photographers among us focused their attention on images, while reporters in the class brought in writing samples we found particularly compelling and practiced writing descriptive, authoritative narratives. We read our pieces aloud. Early in the semester, professors created reporter-photographer teams and assigned us to reservations, so it was as a team that we researched our areas, identified potential sources, and brainstormed story ideas.

During much of our class time we discussed specific story ideas. Since most of us would have just one shot at reporting our story—we’d spend about four days at the reservation doing our reporting—the professors urged us to leave Missoula with a firm story idea in mind. We spent a great deal of time on the phone and the Internet looking for ideas that fit our theme.

Reporting As a Team

Katie and I chose a topic late, just several days before we left on assignment. We had talked to a University of Montana student who grew up on the Rocky Boy’s Reservation, where we were assigned to go. What this student said intrigued us: There were some places in Havre, a town where many Rocky Boy’s residents went to shop, where some Native Americans felt they were treated unfairly because of the color of their skin. Those tensions were most evident at retail stores, bars and restaurants, the student told us.

Before we left, our professors stressed that it would be best if we reported on something we witnessed firsthand rather than relying on second-hand accounts. This guidance made us think more about the many potential problems we might have with reporting this story, but since our other ideas seemed less promising, Katie and I decided to investigate it. Our teachers also reminded me that it is difficult to know what motivates people’s actions, so it would be especially important to describe scenes without offering my interpretation of them. “Show, don’t tell,” became my mantra.

For four days we worked on the story, covering a great deal of ground. We interviewed employees at clothing stores, hardware stores, restaurants and bars. We talked to tribal college educators and police officers. We met with people in their homes. We went to visit the jail and on a ride-along with a police officer. The constant challenge was to figure out what questions to ask and how to ask them.

Race is a sensitive subject, so often I would simply ask about the relationship between people who live in Havre and people who live at Rocky Boy’s. Since part of what I was investigating was how people were treated in stores, I also asked my sources, both customers and clerks, about shopping and store policies. People were generally candid and eager to talk.

Immersing myself in a new place and working on an in-depth story was invigorating. I was devoted to this project, and the reporting time passed quickly. Sometimes Katie and I separated to save time, but often we worked together. I found it was generally valuable to work as a team. When we met with sources, having two of us there seemed to put them more at ease. Katie was skilled at carrying on the conversation when I furiously scribbled notes, and my questions helped keep our sources relaxed when she was shooting.

Being part of a team was also helpful because we were able to discuss our story as it unfolded. If we needed an additional interview, we brainstormed about how to find the right person. When Katie wondered what image might best illustrate an idea, we talked about that, too. After each interview we’d discuss it, sharing what stood out to each of us.

Despite my initial uncertainty that the story would pan out, I became amazed at how many different angles our investigation could have taken. From our initial unplanned interview we were directed to additional sources and, for each person we interviewed, there were three more people that we simply didn’t have time to talk to. The assignment illustrated the wealth of stories waiting to be reported from these communities.

Responses to the Reporting

Most fascinating has been observing how the communities reacted since “Bordering on Racism” was published. Several local papers did follow-up articles describing people’s responses. One of my sources was angry and said I took her comments out of context. The mayor of Havre called it the most slanted story he had ever read. But another person called it hauntingly accurate, and leaders in towns around the state said they face similar sorts of racial friction in their communities.

People have been pledging changes, too. A national clothing store chain announced that it was increasing its employee diversity training after a clerk in their Havre store told me, “I don’t mean to be racist, but there are a lot of Native Americans around here, and that’s who we have to watch.” A mediator from the U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service visited Havre to help town and reservation residents improve communication, and Havre city officials announced that its once-defunct Native American Affairs Committee would be revived.

Visiting a new community and trying to make sense of it in four days was an enormously difficult task. But the response to the story is an illustration that journalism is important because it can directly affect people’s lives. For me, it’s also a powerful reminder that at its best journalism can help us better understand the places we’ve never been to and the people who live there—even those who might initially seem foreign.

Anne E. Pettinger is a second-year graduate student in print journalism at the University of Montana.

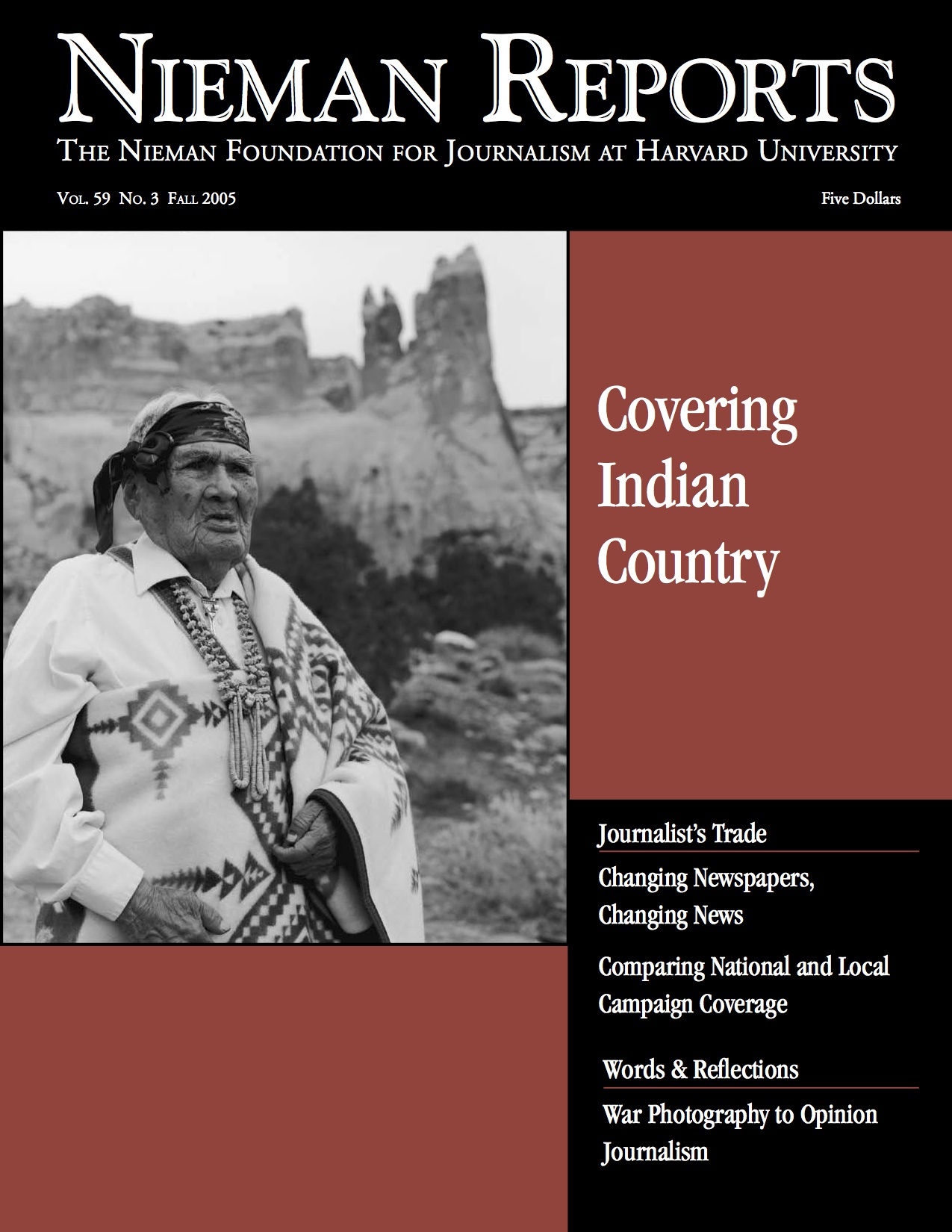

“Havre is a small isolated town located 25 miles from Rocky Boy’s Reservation. After visiting local businesses, it became apparent that these neighboring towns had conflicting opinions about the tensions between Natives and non-Natives.” — Katie Hartley

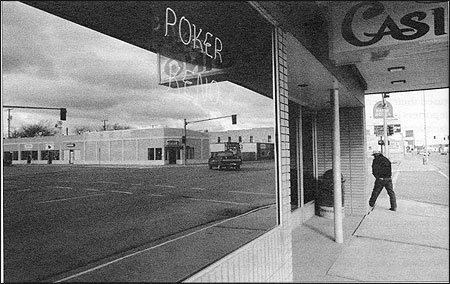

“We expected that stories of racially motivated conflicts and tension would be few and far between on our first visit to Rocky Boy’s Reservation. What we found instead is that everyone we spoke with had a story to tell about local racism. Joe Big Knife recounted an incident at a Havre store that he felt humiliated his family.” — Katie Hartley

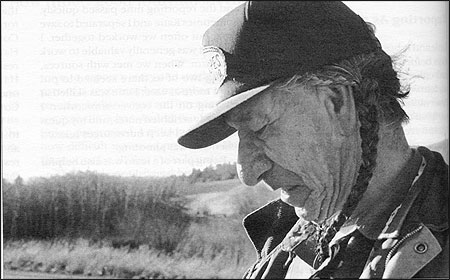

“The Rocky Boy’s Reservation lies between ranch lands and the beautiful rolling hills of the Bear Paw Mountains.” — Katie Hartley

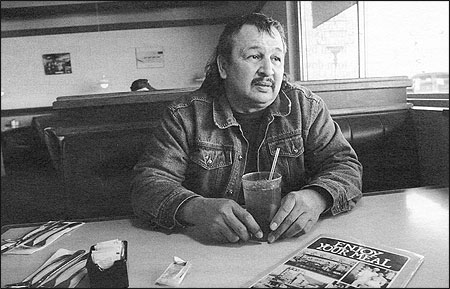

“In a Havre restaurant, Kenny Blatt, a Rocky Boy’s resident, tells us that he has built a rapport with many people in Havre. Blatt, however, expressed his concern that there were other Natives who were not receiving the same hospitality.” — Katie Hartley

Photos by Katie Hartley.