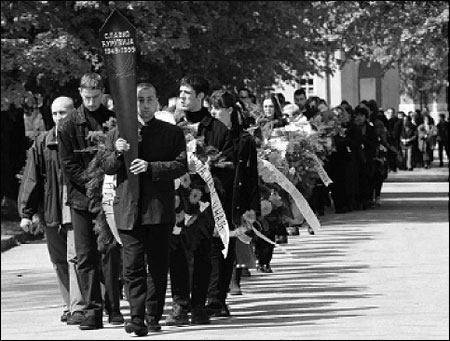

A funeral procession leads the coffin of prominent Serbian opposition journalist Slavko Curuvija, owner of the daily Dnevni Telegraf, who was killed in Belgrade April 11, 1999. Photo courtesy of Reuters.

On the façade of Jadran Hotel in Kosovska Mitrovica (in Kosovo) there is a stone sculpture of a woman with seven children gathered at her feet. She is the grandmother of my father, who is one of those children. When my father’s forebears, who were paupers in what today is the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, returned from America about 1919 as rich folks, they moved to Kosovo. History tells us that their ancestors moved away from that place in the 14th century, fleeing from the Turks.

Serbs claim they have emotional ties to Kosovo, that unhappy land. The only remnant of the Zarkovic family in Kosovo is the petrified sculpture of a mother with seven children. I was born in Belgrade but I traveled to Kosovo many times as a reporter. One summer night in 1981, the howling of dogs woke me from my slumber. It was only midnight. I approached the window and from the fifth floor of Hotel Grand in Pristina witnessed a ghostly spectacle. A pack of dogs were howling in the dark, their heads turned toward the lit hotel. The dogs controlled the empty streets in this dark city. Because of demonstrations by Albanians, a curfew had been declared.

Despite my origins and experience, I do not dare present myself as someone who is an expert on Kosovo. However, the sculpture of my great-grandmother and an ominous midnight experience give me an advantage over many people who spent tons of printing ink on proving that the solution to the knot of the Balkan problem is a bombing campaign. Today, more than one year after the bombing of Yugoslavia began (March 24, 1999), many things can be viewed more clearly, explained in greater detail, and understood more easily. This does not mean that the world has become any smarter or better for it.

Regarding journalism during the war, there is an important point I’d like to make, and it concerns the role the independent media in Yugoslavia played during that time. By independent media, I mean those journalists who really represent the democratic potential of this country and who have been battling Milosevic’s policies with far greater sincerity (including his policies toward the Albanians of Kosovo) and for a far longer period than the Western alliance has done. These journalists had very good political reasons and made very solid political judgments when they decided to accept the rigorous conditions of government censorship during the 80 days of bombing and to continue doing their jobs, which in any case is a mere matter of professionalism.

VREME weekly magazine, where I am Editor, is a leader in setting professional and political standards in this not-so-small group. In making this decision, we took into account the following reasons:

- We were unwilling to abandon our readers to pure propaganda, either to the propaganda of the Serbian government or to the propaganda articulated by spokesmen of the Western alliance.

- It was not fair to turn our backs on faithful readers who are suffering on a daily basis as victims of war, when our job is to inform people to the best of our abilities.

- The division into the good and the bad guys, into victims and criminals, was too simplistic.

- The war will last several months, despite whatever anyone said to the contrary at the beginning: It will solidify the position of President Slobodan Milosevic.

- Kosovo will remain a political problem: The air attacks do not solve any problems.

- War is threatening the fragile, democratic potential of Serbia, Montenegro and Kosovo.

When we look back at the dangerous reality of that time and we exclude several refugees who clamored loudly about the so-called betrayal by the Serbian independent media, reactions by the Yugoslav readers were universally positive. Lack of understanding about our decision to go along with the censorship rules was proportional to the geographic and emotional distance between the clamoring critics and the place where the bombs were actually falling.

After “the period of censorship,” however, questions began coming at us from people throughout the world. They’d ask me questions such as, “Why did you publish during the war?” or “Didn’t you become Slobodan Milosevic’s allies by publishing?”

In the beginning, I gave lengthy and detailed answers to the first question. Then one day I came across a convenient paradox in an article by fellow journalist Dimitrije Boarov. His message effectively curtailed my willingness to respond. In a VREME article, Boarov wrote that had the citizens of Novi Sad known that the political fate of Milosevic depended on the bridges in their city, they would have destroyed them themselves! The situation is much the same with the media. If the media decided to be silent or to quit publishing, it would just be a nice present for Milosevic. Apart from his propaganda drums, there wouldn’t be other voices heard in Serbia. As for the issue of members of the independent media “being allies,” it can be answered by looking at actions. This year Milosevic is concentrating on destroying the independent media in Serbia. Hardly the way one would treat his allies!

It is, however, worth pointing to one interesting political fact. Anyone who wanted to use his or her head realized very quickly that there is censorship of the censors themselves, and we were given to learn this in very perfidious ways. Who was at the head of that supreme censorship could only be guessed at. Perhaps he or they were fictitious.

This would have been masterful deception had that actually been the case. The interposition of an invisible power in the game being played between the government and the citizens appears efficient. One office is carrying out repression by limiting and denying certain previously relevant rights and freedoms. Its power is small when compared with an invisible authority. This invisible authority acts ominously; in time, you come to recognize it as your own fear. You are constantly being sent the message: Yes, you passed the censorship, but that means nothing, you must satisfy us also!

After considerable argument and battle—that was unwarranted by the actual news item—VREME managed to publish that Radio B92 had been essentially closed by an official decision passed by Belgrade’s Court of Commerce. But the censors asked VREME’s editor in chief that in the event problems arose he would say that the censors had not seen this news item! We did put together an entire page on the death and funeral of Slavko Curuvija, Founder and Editor in Chief of the daily Dnevni Telegraf and weekly Evropljanin, who was murdered at his doorstep in Belgrade on April 11, 1999. Three days earlier, media controlled by Milosevic published that Curuvija was an ally of the enemy who was advocating NATO bombing of Yugoslavia. We managed to convince the censors that it was necessary for us to write about his death and funeral. This time the censors told us we could get into real trouble for doing so but that we should say that the material passed the censors! When we asked the censors whom we were supposed to lie to, whom we had to tell the truth to, and who is the one who decides who gets closed down despite the fact that the censors approve material, we never got a straight answer.

Every dictatorship is based on this invisible power. The supreme principle is fear, and we saw this in the eyes of the censors. Under such conditions we had to bend over backwards in order to bring as many facts as possible to our readers. Our security was in jeopardy.

Statements made by Western officials also contributed to making our jobs more difficult and our security more perilous. For instance, Robin Cook, British Minister of Foreign Affairs, announced details about the amount of aid his government gave to Belgrade’s Radio B92. This gave Yugoslav authorities arguments for accusations similar to those that probably led to the murder of Curuvija. NATO spokesman Jamie Shea announced that Veton Surroi, Baton Haxhiu, Shkelzen Maliqi, and others had been killed. After that, we spoke to Veton Surroi over a cellular phone. The number of mass gravesites grew staggeringly with the increased intensity of the bombing. Those of us who are more familiar with the political situation and with the actors in the field were suspicious of the sources that NATO quoted.

The citizens of Serbia, who refused to be destabilized by state propaganda and satellite programming of Western stations (watched closely during air alerts) were looking for a balance in the reporting of independent electronic media (Radio Pancevo, for instance) and in newspapers which were still being printed. Perhaps we didn’t have all the important news. Certainly we lacked editorials that would help to explain developments to people. As far as in-the-field reporting goes, we could not even consider it when our movements were limited—foreign reporters were in a slightly better position because the Army occasionally permitted them to travel to Kosovo. But at the very least, the independent media that reported during the war were free from primitive propaganda and from hate speech.

Phillip Knightley’s book, “The First Casualty,” which collected dust on the shelves of various editorial offices in Belgrade prior to the NATO aggression against Yugoslavia, became very popular with our journalists beginning on March 24. This is of little surprise, given that Knightley’s work deals with the history of war reporting and, of course, with censorship from the time of the Crimean War to Vietnam. In short: It is instructive reading.

When a state of war is declared—and in Yugoslavia that state of war was declared when the first bomb fell in Montenegro—censorship naturally follows. This has been the case always, from the battles in Crimea to the massacres in Vietnam, and it exists in different forms in all countries. Conflict between journalists and censors unfolds on the thin frontline, a line dividing two powers, the state and the media. And there is an imaginary line in no man’s land where it is easy to lose sense of what is the protection of the state and the people and what is the protection of those in power. Knightley showed that censorship was most rigorous and perfidious in those countries that want to present themselves as models of democracy and of freedom of the press.

Dealing with censorship is part of the fate and the job description of the journalistic profession amidst the great tragedies of war. It is normal and acceptable as long as it protects the specific defense interest of a country. It respects the convention of sparing a government and its institutions from uncontrolled criticism while war efforts are continuing. But it becomes torture and crime perpetrated over the public word and freedom of thought when someone attempts to protect narrow political interests or to continue media censorship after a war has ended.

Neither Serbian journalists nor the Serbian censors (incidentally, many of the former are predisposed toward doing the job of the latter) were able to avoid the traps of this unpleasant business. In that, we are not alone. At one point in his book, Knightley quotes what one official U.S. censor said in a meeting at the start of World War II: “While the war lasts don’t report anything. When the war ends, report who won!”

All censors have the same logic. A specific problem in Serbia is that in the war between the state and the media, we still do not know who is the winner. When we find out, we will let you know.

Dragoljub Zarkovic is Editor in Chief of Belgrade’s VREME weekly magazine.